Draft:Nomination of Mayors under the French Third Republic

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 3 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 2,522 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

The nomination of mayors under the French Third Republic constituted a process of appointing mayors by the executive power in France during the early years of this republic. The modalities and scope of application were defined by a series of successive laws, including the Law of Picard of April 1871, the Law of Mayors of January 1874, and the Municipal Law of August 12, 1876.

The selection of mayors by the central authority was first implemented under the First Empire, and its subsequent contours were modified by subsequent regimes. In 1871, the Third Republic saw the nomination of mayors voted on by a National Assembly initially favorable to local liberties. However, Adolphe Thiers was able to secure the necessary consent in the context of communal uprisings. In 1874, the conservative majority extended it to suppress resistance to the Moral Order policy and prevent the electoral ascendance of the Republicans. In 1876, there was a final return to the 1871 consensus. Ultimately, the laws of March 28, 1882, and April 5, 1884, reverted to the principle of mayoral election by the municipal council. However, the government Republicans' mistrust of what they deemed excessive decentralization resulted in the continued state control over municipal elected officials.

From the Empire to the National Defense

[edit]

The precedent for nomination was established at an early date. Following the creation of municipalities and the establishment of the election of municipal officers by the decrees of December 1789, which occurred during the French Revolution, the nomination of mayors by the central authority was implemented by the law of February 17, 1800 (28 pluviôse year VIII), which occurred during the First Empire. The contours of this process then varied according to the successive regimes of the Restoration, the July Monarchy, and the Second Republic.[1]

Following the coup d'état of December 2, 1851, the nomination of all mayors was implemented by decree from March 1852. This was following a draft law prepared by the State Council of the Second Republic in 1850, which had been designed to continue the nomination process. The municipal law of May 5, 1855, reaffirmed the nomination policy[N 1] while acknowledging the necessity for the mayor to govern in consultation with the municipal council. In a tentative reversal of the authoritarian Empire's legislation, the local electoral law of June 1865 indicated that mayors should be appointed within the elected municipal council.[3] Ultimately, the law of July 22, 1870, stipulated that mayors and their deputies must be chosen within the municipal councils,[N 2] a provision effective for the municipal elections of August 1870.[5][3]

In the aftermath of the Battle of Sedan, the restoration of the French Republic on September 4, 1870, witnessed the ascendance of a government comprising Republican parliamentarians, spearheaded by Jules Favre, who were staunch proponents of the universal suffrage espoused in the 1848 Revolution. Consequently, from the inception of the Government of National Defense, the organization of elections commenced, as it was believed that this would prove to be the most efficacious method for restoring civil harmony domestically and peace externally.[6] On September 16, 1870, a decree established the date for the election of municipal councilors as September 25. Two days later, the government issued a decree that a municipal election would also take place in Paris, under the same conditions as the rest of the French municipalities.[7] However, the leaders of the National Defense were disillusioned when it became evident that Bismarck was not engaged in hostilities with the Empire but with France. As a result, the elections were subsequently postponed indefinitely.[8][9] The municipal councils, which had been dissolved by the government upon its formation, were replaced by provisional municipalities chosen by the executive power. These mayors were appointed among Republicans, allowing them to gain local influence. However, in response to protests from defenders of municipal liberties, particularly notable Parisians, the National Defense leaders authorized municipal elections in Paris to elect mayors and deputies of the arrondissements.[9][10] This appeasement measure was a precursor to the outbreak of the Paris Commune.[9] Ultimately, following the signing of the 1871 armistice, the National Assembly was elected on February 8, 1871.[11]

Practice and Legislation of Mayor Nomination from 1871 to 1882

[edit]Law of Picard (1871)

[edit]

To resume the preparation of municipal elections, which had been interrupted by the Government of National Defense, Interior Minister Ernest Picard submitted a draft law on their organization to the Assembly on March 23, 1871.[12] However, between September 1870 and March 1871, there had been a profound shift in the political balance of power, with the election of a majority of monarchist parliamentarians and the appointment of conservative Republican Adolphe Thiers as president of the Republic.[13] The Picard Law was therefore largely based on the law of July 3, 1849, which had been voted by the Party of Order, of which Thiers was already one of the leaders. The law provided that communes with more than 6,000 inhabitants would have their mayor appointed by the executive, while the municipal council of other communes would have full latitude to elect theirs.[14] Thiers, maintaining the Bonapartist distrust of municipal liberties, saw in them a revolutionary danger; the monarchists, for their part, were divided. Many provincial notables were attached to decentralization and local liberties, showing themselves to be more liberal than Thiers.[15][16]

On March 31, 1871, Anselme Batbie, a center-right deputy and the rapporteur of the parliamentary commission tasked with examining the project, delivered favorable conclusions. Nevertheless, an unanticipated coalition from the center to the left voted in favor of the amendment proposed by Agénor Bardoux, Amédée Lefèvre-Pontalis, and Amable Ricard. These centrists secured the right for all communes to elect their mayor, appealing to the instinctive repulsion of many colleagues against the authoritarianism of the Second Empire. However, the parliamentary commission did not concede defeat, and Auguste Paris submitted an additional provision on its behalf, temporarily appointing mayors and deputies in all departmental and arrondissement capitals and all communes with more than 20,000 inhabitants.[14] The communes affected by these restrictions—excluding Paris—numbered 460.[17]

In addition to the deliberations of the Assembly, civil unrest was occurring in major French cities following the establishment of the Paris Commune. Consequently, when Thiers addressed the Assembly on April 8, 1871, he made specific reference to the assault led by General La Villesboisnet against the insurgents of the Marseille Commune three days earlier:[18]

Certainly, when, in a city like Marseille, which is a very enlightened city, no one contests it, which is wealthy city, having, therefore, a great interest in maintaining order, five hundred sailors must be brought down from their ships to restore compromised order; when the prefecture must be taken by storm... And do you know how? With boarding axes! (Movement in the tribunes.) Under such circumstances, we are asked to leave the government of large cities to the whims of election; gentlemen, I must say, it is unacceptable! (Loud and numerous marks of assent.[19])

In his speech, Thiers placed the Assembly in a position where they would have to either approve the Paris provision or face his resignation. By doing so, he forced the hand of parliamentarians who were aware that he was indispensable for negotiations with Bismarck. As a result, he was able to reconstitute an alliance that was united by the goal of maintaining social order. This alliance ultimately led to victory, with the majority making "the sacrifice of their decentralizing sympathies," according to Gabriel Hanotaux.[20][17] The law about municipal elections was ultimately enacted on April 14, 1871.[17] Paris was accorded a distinctive status, with an elected municipal council and mayors and deputies appointed for the arrondissements.[9] Subsequently, the election of extreme-left politician Désiré Barodet as mayor of Lyon resulted in the enactment of the law of April 4, 1873, which abolished the central mayoralty of Lyon, due to concerns about potential agitations similar to those witnessed during the Lyon Commune.[21]

Law of Mayors (1874)

[edit]A law of resistance

[edit]The inclination of the monarchist notables for decentralization subsequently diminished. This was observed by Anatole de Melun on March 26, 1873, a date that preceded the overthrow of Thiers by a mere few days: "The current of opinions changes quickly. At that time [1871], we were struck by the mistakes of the past; today, we are much more concerned about the dangers threatening the future; hence, our ardor for reforms and decentralization has greatly diminished." Thus, the Moral Order coalition prepared measures to temper universal suffrage in the face of Republican and Bonapartist dangers.[17][22] The "mayors' law" sought to hinder the Republicans' conquest of municipalities: reverting to authoritarian Empire practices, it provided for the president's appointment of mayors and deputies of departmental, arrondissement, or canton capitals; and their appointment by the prefect for other communes.[17][23] Additionally, mayors could be appointed outside the municipal council. The government presented this law as temporary "until the vote on the organic municipal law."[17]

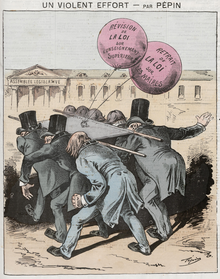

During the parliamentary debate, Pierre Baragnon, Secretary of State for the Interior, advanced the government's position on the proposed legislation.[24] In a notable intervention, he stated: "France must move forward!"[25] His superior, Albert de Broglie, explained: "I am convinced it is impossible to leave ministers, prefects, and sub-prefects responsible for enforcing laws when they cannot freely choose or dismiss the agents they are forced to use."[26] Opposing them, jurist Paul Jozon, Deputy of the Republican Left, defended public liberties; denouncing a law that aimed to transform mayors into "sub-sub-prefects," he urged Republicans to oppose the government's actions because they had "everything to gain from liberty: it is our best ally, our best guide."[27] Louis Blanc added, exclaiming: "What they want are 72,000 electoral agents wearing the municipal sash!"[26] This conflict illustrated the ambiguity introduced since the French Revolution by combining mayors' municipal prerogatives and functions delegated by the central administration to communes, making them de facto "agents of the government."[28]

The "Law of Mayors" was enacted on January 24, 1874, with a vote of 359 to 318.[26] This narrow margin indicated the internal divisions within the conservative majority, as Marshal MacMahon had been elected with 390 votes. Among the dissenters was the Marquis de Franclieu, who had submitted a preliminary question on January 8, 1874, requesting that the debate be postponed until the organic municipal law was discussed. This legitimist representative expressed concern about the potential damage of governmental arbitrariness and proposed ensuring social order by establishing municipal elections with the election of municipal councils by corporative vote and free election of the mayor by the council.[26][29]

-

Pierre Baragnon, speaker for the Conservative majority.

-

Paul Jozon, Republican opposition speaker.

The "Combat Government" and the mayors

[edit]

On January 22, 1874, Baragnon distributed a circular from the Broglie cabinet requesting that prefects utilize revocation against mayors who opposed the Moral Order policy.[24] In this circular, the Duke of Broglie reaffirmed his intention to combat the demagoguery exhibited by the Republican Party. "A regrettable outcome has irrevocably discredited the system of electing mayors by municipal councils. The selections made by municipal councils, influenced by partisan considerations, have frequently resulted in individuals who, due to their incompetence, background, or personal shortcomings, have undermined the integrity of the positions they have assumed. Consequently, we have witnessed the transformation of some major cities' municipalities into centers of demagoguery.[26] This firm stance resulted in the replacement of numerous officials, with several hundred revocations pronounced, including those against individuals of a moderate left-center persuasion, such as Hippolyte de Tocqueville (mayor of Nacqueville), Charles-Victor Rameau (mayor of Versailles), and Jules Siegfried (deputy mayor of Le Havre).[30] In the Nord department, the cities of Roubaix, Cambrai, and Dunkirk were affected by these administrative measures.[31] To replace the mayors who had been revoked, the Duke of Broglie notably selected former mayors from the Second Empire, to extend the conservative majority to Bonapartists.[30]

In many instances, mayors subsequently removed from office combined their opposition to the incumbent government with a rejection of the moral values that the government sought to promote. For example, the Republican mayor of Selles-Saint-Denis was dismissed from his post after he permitted "scenes of public immorality" to occur in the drinking establishment that he owned and operated through his deputy.[32] In other instances, Broglie demonstrated restraint by declining to comply with certain revocation requests from his prefects. For instance, when the municipality of Liniez declined to approve the requisite budget for repairing the rectory and church in February 1874, despite its authority to do so, the Minister of the Interior opted to register the expense instead of immediately dissolving the council as demanded by the sub-prefect of Issoudun.[32] In the National Assembly, Deputy Mayor Jean-Baptiste Godin, who had been removed from office for promoting the socialist phalanstery system in his commune of Guise, directly opposed the conservatives by refusing to relinquish his functions until a replacement was found. This led the Moral Order coalition to confirm his revocation in a parliamentary session.[33] The appointment of mayors was also a matter of symbolic significance. In municipalities with municipal buildings—the obligation for municipalities to have a "town hall building" dates from the law of 1884—replacing a Republican with a conservative often entailed the relocation of Marianne's bust in favor of Marshal Mac Mahon's portrait or even a crucifix.[3]

Regarding the implementation of the "mayor law" in response to the anticlerical actions of select municipalities—including the secularization of communal schools and hospitals—Mgr Dupanloup advised French bishops to counsel the government on the revocation of mayors. While Cardinal Mathieu declined to pursue this course of action, Mgr Bourret and Mgr Paulinier supported the strategy.[34]

In general, the mayors of the Moral Order could not gain significant local influence. However, they provided a rationale for Republicans to "over-politicize" the 1874 municipal elections, a politicization further intensified by incorporating mayors into the colleges of grand electors, whose role was to elect senators. This resulted in a situation where Gambetta could express satisfaction, noting that "there are communes that today will not conduct a single municipal council election without first inquiring about each candidate's political opinions."[30][35]

In the 1876 legislative election campaign, the moderate Republican daily newspaper Le Temps expressed concern that right-wing mayors might use their local influence to affect district ballots. Consequently, it advocated for the dismissal of the officials of Montauban, Isidore Delbreil, and Avignon, Jean du Demaine, under the "mayor law." The Louis Buffet government, "divided between the center-left and center-right," declined to yield to the pressures from either side and did not utilize the law to a significant extent in influencing the legislative elections. Consequently, Demaine prevailed over Léon Gambetta in the Avignon arrondissement , whereas Delbreil was unsuccessful in his bid to enter the Chamber of Deputies.[36] The center-left, victorious in the 1876 elections, subsequently invoked the mayor law to remove conservative mayors and deputies appointed by the Broglie cabinet outside the municipal councils. Interior Minister Amable Ricard underscored the necessity to "restore the indispensable harmony between elected councilors and representatives of municipal power."[30]

Municipal Law of August 12, 1876

[edit]Return to the 1871 compromise

[edit]

The Republican victory in the 1876 elections resulted in the ascendance of conservative Republicans to positions of authority. Immediately, radicals—including Clemenceau, Pelletan, and Naquet—demanded the repeal of the "mayor law" and the resumption of complete elections, which they saw as necessary for the furtherance of their political objectives.[37][38] Additionally, concerns were raised by those on the left regarding the elections to the Senate, which had been recently established by the law of February 24, 1875.[37] The second Interior Minister of the Dufaure cabinet, Émile de Marcère — a figure of the center-left —, in consideration of the primary objective being the dismissal of Broglie's mayors, declared himself to be aligned with the principle of complete appointment and opposed Léon Gambetta and Jules Ferry.[39] Those who had campaigned for decentralization were reluctant to reduce the central government's powers to implement their program. Consequently, Gambetta declared from the rostrum, "I am not a decentralizer!"[37][17] Following considerable deliberation and a challenging vote, the law of August 12, 1876, endorsed by the cabinet and Jules Ferry, reverted to the system established by the Picard law, while gradually preserving the appointment of mayors and deputies in canton capitals.[37][40] The provisional nature of this structure was once more underscored, although Gambetta opposed this approach.[39][40]

Sixteenth of May and Republican Reconquest

[edit]Amid the crisis that unfolded on May 16, 1877, Marshal Mac Mahon summoned the Duke of Broglie, who assumed the role of President of the Council, and Oscar Bardi de Fourtou, who assumed control of the Interior Ministry.[41] Bardi de Fourtou sought to leverage the opportunities presented by the 1876 law to diminish the local influence of the Republicans and facilitate electoral maneuvers by the conservatives. He revoked the positions of 1,743 mayors, representing 4% of the officials, and 1,344 deputies, and dissolved 613 municipal councils.[41][30]

Among the municipal officials dismissed were 48 deputy mayors who had endorsed the manifesto of the 363. Of the 35 mayors re-elected to the Chamber by voters, the majority resumed their seats on the benches of the Republican Left and Republican Union. In the view of Le Temps, the dismissed were effectively reappointed by universal suffrage.[41] Accordingly, the newspaper applauded the consolidation of deputy and mayoral roles as a laudable objective for those identified as "good Republicans." In the aftermath of the left's ascendance to executive authority, the prefects, invoking the 1876 law, allocated the affected mayoral positions to prominent Republican figures within the departments, frequently prioritizing an integration with parliamentary responsibilities. This resulted in the establishment of the Republic in municipalities, which later became one of its most reliable bases of support. This was achieved through the "territorial monopolization of power positions" practiced by opportunists and radicals in their struggle against conservatives for control of electoral markets.[42][26]

End of the appointment of mayors

[edit]Law of 1884

[edit]The conclusion of the mayoral appointment process was protracted, coinciding with the advent of the "Republic of Opportunists." Between March and May 1877, a municipal organization law proposed by Jules Ferry was under discussion, but the political crisis of 16 May ultimately prevented the project from being implemented.[3][40] The law of April 21, 1881, restored the municipal regime in Lyon to that of other French municipalities, with a few exceptions, by reconstituting the central town hall.[40] Léon Gambetta excluded the mayoral appointment reform from his "grand ministry" program, declaring his attachment to "French centralization, which corresponds to the history and spirit of unity of France" and expressing concern about the potential dangers of "these [liberal] theories in a country whose Revolution cemented all parts to make it stronger."[37] Following Gambetta's downfall, the Freycinet cabinet passed the law of March 28, 1882, which guaranteed the election of all mayors and deputies by municipal councils. This legislation was supported by opportunists.[39][40] The other provisions regarding municipal organization were postponed to a later law, as they were considered less urgent and consensus difficult to achieve.[37] The "municipal organization" bill was debated for a further two years; it was finally adopted under the second Ferry cabinet[37][39] and became the municipal law of April 5, 1884.[43]

The document confirmed the election of municipal councils, which comprise between 10 and 36 members and are established for four years. It also confirmed the election of mayors and deputies within these councils. Nevertheless, the central government retained control over municipalities. Being rapporteur of the law, Émile de Marcère asserted that the commune is "subject to the general laws of the State, and it cannot violate them without exposing France to a genuine state of anarchy." He further maintained that it "should not engage in politics."[26][39] Additionally, the 1876, 1882, and 1884 laws upheld Paris's distinctive regulatory framework.[37][44] Moreover, the 1884 law permitted the prefect to determine the suspension of municipal councils (Article 43), and the Council of Ministers was vested with the authority to dissolve them and appoint a special delegation to oversee current affairs until new elections—scheduled within two months—were held (Article 44).[39][45] Concerning the mayor and deputies, they may be suspended by a prefectural order for a period not exceeding one month, which may be extended to three months by the Minister of the Interior. Such appointments may only be revoked by a presidential decree. "The revocation of an elected official's position automatically renders them ineligible to hold the same or similar functions for one year, commencing from the date of the revocation decree" (article 86).[45] To illustrate, in May 1886, the monarchist mayor of Barbentane, Pierre Terray, was removed from office by presidential decree due to a brawl between Republicans and royalists during a communal festival.[46] The suspension and revocation procedure was reformed by the law of July 8, 1908, with only minor alterations.[38]

World War II

[edit]In the context of the outbreak of the Second World War and as a consequence of the signing of the German-Soviet Pact, the Daladier cabinet adopted the decree of September 26, 1939, which resulted in the removal of the 27 communist municipal councils in the Paris region. This was followed in October 1939 by the removal of the 37 communist municipalities in the Nord and 11 in the Pas-de-Calais.[47][48][49] In these two departments, the dismissals of 576 elected officials—including municipal, district, and general councilors—and 358 elected officials were pronounced, respectively. The purge was completed by the law of January 20, 1940, which provided for the dismissal "of any member of an elected assembly who was part of the French Section of the Communist International" after October 26, 1940. This resulted in the dismissal of 2,500 municipal councilors.[48] In their place, special delegations were appointed by the Minister of the Interior to oversee the municipalities.[48][50][49]

Following the Vichy regime and the subsequent Liberation, there was a brief return to the appointment of mayors. This was enabled by the act of November 16, 1940, "on the reorganization of municipal bodies," which provided for the appointment of mayors by the executive power. The appointment of mayors, deputies, and municipal councils in municipalities with more than 2,000 inhabitants was permitted, for example, by decrees of the Minister of the Interior Darlan on May 9, 1941, which resulted in the appointment of mayors in numerous municipalities in the Seine department.[48][51][52][53] In the context of the Liberation, the ordinance of April 21, 1944, which provided for the reinstatement of mayors in office as of September 1939, was used by the Liberation prefects as a basis for implementing numerous changes at the municipal level.[48][54] This ordinance was preceded by an ordinance of the French Committee of National Liberation in London on December 15, 1943, issued after the liberation of Corsica. This ordinance declared the nullity of Petainist laws in this regard, canceled the designations made in Corsica, and established special delegations appointed by the London Government until it was possible to organize elections.[N 3]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "The mayor and deputies are appointed by the Emperor in the chief towns of the department, district, and canton, and municipalities with three thousand inhabitants and above. In other municipalities, they are appointed by the prefect in the name of the Emperor. They must be at least twenty-five years old and registered in the municipality in the role of one of the four direct contributions. The deputies can be taken, like the mayor, outside the municipal council."[2]

- ^ "The mayors and deputies appointed by the Emperor or the prefect are chosen within the municipal council."[4]

- ^ "Special delegations will perform the functions assigned to municipal councils. They will be appointed by order of the Commissioner of the Interior. These special delegations will remain in office until the election of new municipal councils."[55]

References

[edit]- ^ Tanchoux, Philippe (2013). "Les « pouvoirs municipaux » de la commune entre 1800 et 1848 : un horizon chimérique ?". Parlement[s], revue d'histoire politique (in French) (20): 35–48. Archived from the original on October 7, 2023. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Article 2 de la Loi sur l'Organisation municipale du 5 mai 1855". Bulletin des lois No. 291. 1855. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d Aubrun, Juliette (2004). "2: Notables, élites et élus locaux : le maire, premier notable en sa commune". La ville des élites locales : pouvoir, gestion et représentations en banlieue parisienne (1860-1914) (in French). Lyon: Université Lyon-II. Archived from the original on December 5, 2023. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Article 1er de la Loi relative à la nomination des maires et des adjoints du 22 juillet 1870". Journal officiel de la République française (in French). July 24, 1870. p. 1319. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Machelon 1989, p. 202

- ^ Rudelle 1982, pp. 13–39, §7

- ^ Rudelle 1982, pp. 13–39, §9

- ^ Rudelle 1982, pp. 13–39, §9-10

- ^ a b c d Guillaume & Guillaume 2012, §30

- ^ "Élections municipales de Paris" [fr]. Le Français. November 8, 1870. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Rudelle 1982, pp. 13–39, §15

- ^ Garrigues 2013, §22

- ^ Rudelle 1982, pp. 13–39, §18

- ^ a b Garrigues 2013, §23

- ^ Garrigues 2013, §21

- ^ Rudelle 1982, pp. 13–39, §32

- ^ a b c d e f g Machelon 1989, p. 203

- ^ Garrigues 2013, §24

- ^ Garrigues 2013, §33-34

- ^ Garrigues 2013, § 24-25

- ^ Robert, Adolphe (1889–1891). "Désiré Barodet". Dictionnaire des parlementaires français (in French). Edgar Bourloton.

- ^ Rudelle 1982, pp. 13–39, § 78

- ^ "Loi relative aux maires et aux attributions de police municipale". Journal officiel de la République française (in French). No. 21. January 22, 1874. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Huard, Raymond (1995). "Baragnon, Pierre Joseph Louis Numa (1835-1892)". Les immortels du Sénat (1875-1918) : Les cent seize inamovibles de la Troisième République (in French). Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne. pp. 209–211. ISBN 979-10-351-0495-5. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Robert, Adolphe (1889–1891). "Pierre, Joseph, Louis, Numa Baragnon". Dictionnaire des parlementaires français (in French). Edgar Bourloton.

- ^ a b c d e f g Machelon 1989, p. 205

- ^ Allorant, Pierre (2009). "Paul Jozon, un jurisconsulte au service de la République". Parlement[s] : Revue d'histoire politique (in French) (11): 118–133. doi:10.3917/parl.011.0118. Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Machelon 1989, pp. 202–203

- ^ "Séance du jeudi 8 janvier 1874". Annales de l'Assemblée nationale (in French). January 8, 1874. pp. 6–9. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e Machelon 1989, p. 206

- ^ Vandenbussche, Robert (1994). "La fonction municipale sous la Troisième République : L'exemple du département du Nord". Revue du Nord (in French). 76 (305): 320. doi:10.3406/rnord.1994.4904. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Allorant, Pierre (2010). "Les municipalités entre le Clergé et l'État dans les départements de la Loire moyenne au xixe siècle". Parlement[s], revue d'histoire politique (in French) (hors-série 6): 76–92. doi:10.3917/parl.hs06.0076. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Marrel 2003, pp. 105–106

- ^ Gadille, Jacques (1967). La pensée et l'action politiques des évêques français au début de la IIIe République (1870-1883) (in French). Vol. I. Hachette. p. 307.

- ^ Machelon 1989, p. 208

- ^ Marrel 2003, pp. 106–107

- ^ a b c d e f g h Machelon 1989, p. 204

- ^ a b Machelon 1996, p. 151

- ^ a b c d e f Guillaume & Guillaume 2012, § 33

- ^ a b c d e Machelon 1996, p. 152

- ^ a b c Marrel 2003, p. 108

- ^ Marrel 2003, p. 109

- ^ Dupont, Paul (1886). "Instruction ministérielle du 15 mai 1884, sur l'application de la loi municipale : Circulaire sur l'ensemble des modifications apportées par la loi du 5 avril 1884 à la législation municipale". Gallica (in French). Paris. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Guillaume 2012, § 34

- ^ a b "Loi sur l'organisation municipale". Journal officiel de la République française (in French). April 6, 1884. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Martin, Denis (2000). "La vie intense du comte Pierre Terray (1851-1925)" (PDF). Barbentane (in French): 4. Archived from the original on June 16, 2024. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Article 4 du « décret relatif aux pouvoirs de tutelle administrative sur les conseils municipaux et les maires en temps de guerre »". Journal officiel de la République française (in French). September 27, 1939. pp. 11770–11771. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e Nivet, Philippe (2013). "Les municipalités en temps de guerre (1814-1944)". Parlement(s) : Revue d'histoire politique (in French) (20): 67–88. Archived from the original on March 30, 2024. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "Les municipalités communistes suspendues dès hier dans la Seine, la Seine-et-Oise et le Pas de Calais". Le Populaire (in French). No. 6076. October 6, 1939. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Conseils municipaux" (in French). No. 240. October 5, 1939. pp. 12030–12032. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Loi du 16 novembre 1940 portant réorganisation des corps municipaux". Recueil Dalloz. 1940. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "M. Peyrouton analyse et commente la loi de réorganisation municipale : les maires et les conseillers municipaux seront nommés par le pouvoir central. Seules les communes de moins de deux mille habitants conserveront le principe de l'élection". Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (in French). No. 275. December 13, 1910. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Maires des communes suburbaines de la Seine". Bulletin Municipal Officiel de la Ville de Paris (in ffr) (131): 391. May 13, 1941. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Cosson, Armand (1992). "La francisque et l'écharpe tricolore : Vichy et le pouvoir municipal en Bas-Languedoc". Annales du Midi (in French). 104 (199): 281–310. doi:10.3406/anami.1992.3740. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Articles 3 et 4 de l'Ordonnance du 15 décembre 1943 concernant la dissolution en Corse des conseils municipaux et des délégations spéciales nommés par l'organisme se disant « Gouvernement de l'État français » et leur remplacement par des délégations spéciales". Journal officiel de la République française (in French). No. 47–48. Londres. December 23, 1943. p. 353.

Bibliography

[edit]Beginnings of the Third Republic

[edit]- Guillaume, Pierre; Guillaume, Sylvie (2012). "Élans et pesanteurs, le réformisme républicain au xixe siècle". Réformes et réformisme dans la France contemporaine (in French). Armand Colin. pp. 7–48. ISBN 9782200249465. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Halévy, Daniel (1937). La Fin des notables : La République des ducs (in French). Paris: Hachette.

- Rudelle, Odile (1982). La République absolue (1870-1889). Histoire de la France aux xixe et xxe siècles (in French). Éditions de la Sorbonne. ISBN 979-10-351-0509-9. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Municipal power

[edit]- Morgand, Léon (1885). La Loi municipale : commentaire de la loi du 5 avril 1884 sur l'organisation et les attributions des conseils municipaux (in French). Vol. II : Attributions. Paris: Berger-Levrault. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Chandernagor, André (1993). Les maires en France (xixe-xxe siècle) : Histoire et sociologie d'une fonction (in French). Fayard.

- Garrigues, Jean (2013). "Quand Ferry et Thiers s'intéressaient aux libertés locales". Parlement(s) : Revue d'histoire politique (in French) (20): 109–121. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Machelon, Jean-Pierre (1989). "Les Communes dans les débuts de la Troisième République : administration et politique". La Revue administrative (in French). 42 (249): 201–208. ISSN 0035-0672. JSTOR 40782252. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Machelon, Jean-Pierre (1996). "Pouvoir municipal et pouvoir central sous la Troisième République : regard sur la loi du 5 avril 1884". La Revue administrative (in French). 49 (290): 150–156. ISSN 0035-0672. JSTOR 40770514. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Marrel, Guillaume (2003). L'Élu et son double : Cumul des mandats et construction de l'État républicain en France du milieu du xixe au milieu du xxe siècle (in French). Institut d'études politiques de l'Université Grenoble II. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

![Paul Jozon [fr], Republican opposition speaker.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Paul_Jozon_en_1870.tif/lossy-page1-85px-Paul_Jozon_en_1870.tif.jpg)

![Paul de Pasquier de Franclieu [fr].](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f1/Paul_de_pasquier_de_franclieu.jpg/84px-Paul_de_pasquier_de_franclieu.jpg)