Thecal sac

| Thecal sac, dural sac | |

|---|---|

A section of the spinal cord with the dura opened to show the interior of the thecal sac. | |

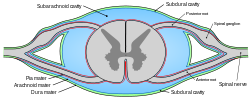

The spinal canal in cross-section; the outer layer of the thecal sac, the dura, is colored green and the subarachnoid space is blue. | |

| Anatomical terminology |

The thecal sac or dural sac is the membranous sheath (theca) or tube of dura mater that surrounds the spinal cord and the cauda equina. The thecal sac contains the cerebrospinal fluid which provides nutrients and buoyancy to the spinal cord.[1] From the skull the tube adheres to bone at the foramen magnum and extends down to the second sacral vertebra where it tapers to cover over the filum terminale. Along most of the spinal canal it is separated from the inner surface by the epidural space.[2] The sac has projections that follow the spinal nerves along their paths out of the vertebral canal which become the dural root sheaths.[3]

Clinical significance

[edit]The lumbar cistern is part of the subarachnoid space. It is the space within the thecal sac which extends from below the end of the spinal cord (the conus medularis), typically at the level of the first to second lumbar vertebrae down to tapering of the dura at the level of the second sacral vertebra. The dura is pierced with a needle during a lumbar puncture (spinal tap). For epidural anesthesia an anesthetic agent is injected into the space just outside the thecal sac and diffuses through the dura to the nerve roots where they exit the thecal sac.[4][5] For spinal anaesthesia in general, an injection can be given intrathecally into the subarachnoid space, or into the spinal canal. This route of administration may also be used for the delivery of drugs which will evade the blood–brain barrier.[6]

Disruption of the dural sac may occur as a complication of a medical procedure, or as a consequence of trauma causing a cerebrospinal fluid leak, or spontaneously resulting in a spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak.[7]

If the spinal cord is not free to move within the thecal sac due to abnormal tissue attachments, especially during growth, tethered spinal cord syndrome may occur.[8]

In a split cord malformation, some portion of the spinal cord is divided into parallel halves. The thecal sac may be divided and surround each half with a spike of cartilage or bone dividing the halves (Type I), or both halves may be present within the same sac where the dura is bound to a band of fibrous tissue (Type II).[8]

References

[edit]- ^ "tethered cord".

- ^ Susan Standring (7 August 2015). Gray's Anatomy E-Book: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 764–. ISBN 978-0-7020-6851-5.

- ^ Moore, Keith (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ John T. Hansen (14 February 2014). Netter's Clinical Anatomy E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4557-7063-2.

- ^ Virginia F. Schneider (2013). "15. Lumbar Puncture". In Richard W. Dehn and David P. Asprey (ed.). Essential Clinical Procedures: Expert Consult - Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 146–155. ISBN 1-4557-0781-3.

- ^ Dip, P.G. "Intrathecal route of drug delivery can save lives or improve quality of life". Pharmaceutical Journal. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Nafi Aygun; Gaurang Shah; Dheeraj Gandhi (5 December 2013). Pearls and Pitfalls in Head and Neck and Neuroimaging: Variants and Other Difficult Diagnoses. Cambridge University Press. p. 475. ISBN 978-1-107-47052-1.

- ^ a b Dias, M.; Partington, M. (2015). "Congenital Brain and Spinal Cord Malformations and Their Associated Cutaneous Markers". Pediatrics. 136 (4): e1105–e1119. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2854. ISSN 0031-4005.