E. E. Cummings

E. E. Cummings | |

|---|---|

E. E. Cummings in 1953 | |

| Born | Edward Estlin Cummings October 14, 1894 Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 3, 1962 (aged 67) Madison, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Occupation(s) | Author, artist |

| Signature | |

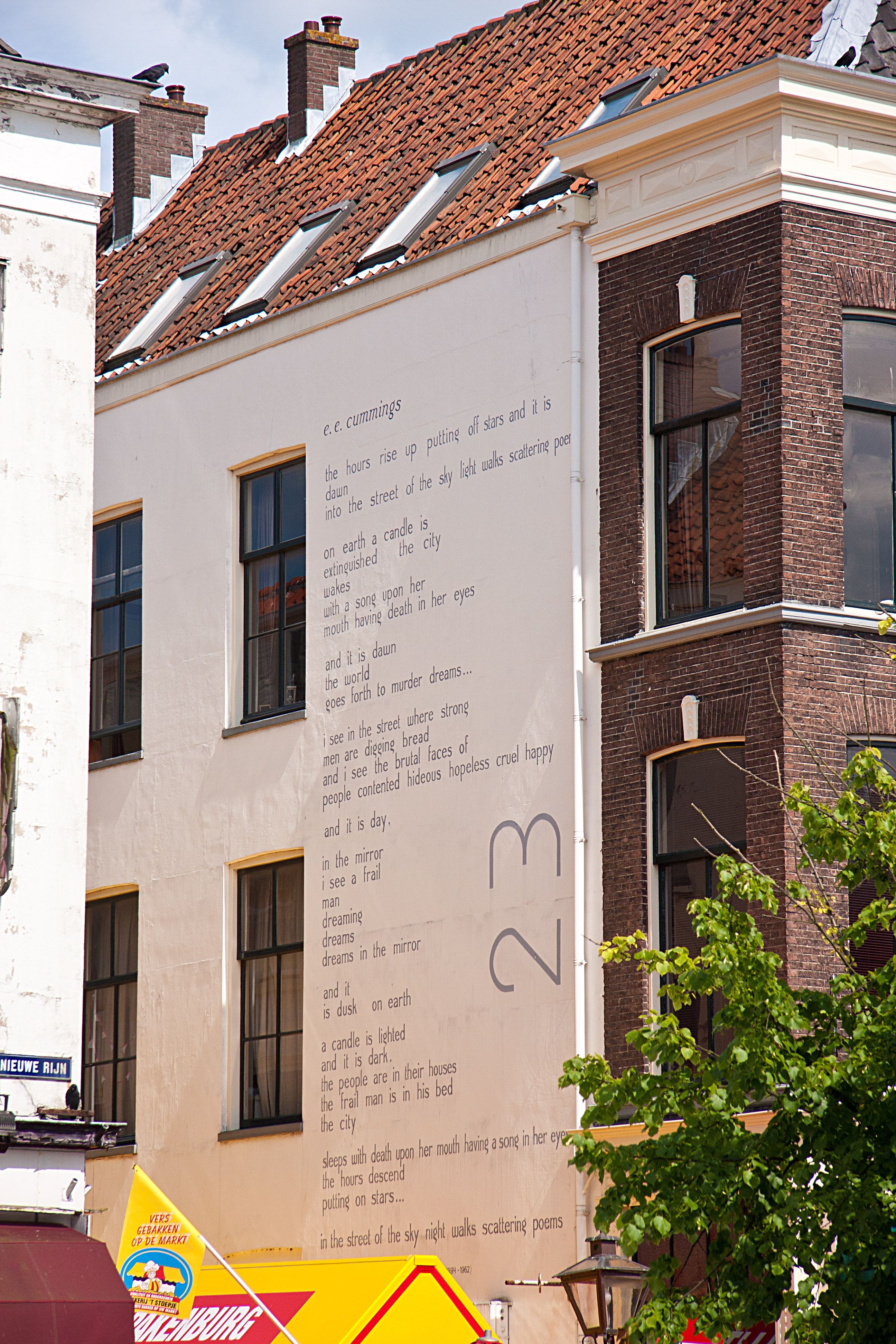

Edward Estlin "E. E." Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), often stylized as e e cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompassed approximately 2,900 poems; two autobiographical novels; four plays; and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as an eminent voice of 20th-century English literature.

Life

i thank You God for most this amazing

day:for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky; and for everything

which is natural which is infinite which is yes

From "i thank You God for most this amazing" (1950)

Early years

Edward Estlin Cummings was born on October 14, 1894, to Edward Cummings and Rebecca Haswell Clarke who were Unitarian. They were a well-known family in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father was a professor at Harvard University and later the nationally known minister of Old South Church in Boston, Massachusetts. His mother who loved to spend time with her children, played games with Cummings and his sister, Elizabeth. From an early age, Cummings's parents supported his creative gifts.[1] Cummings wrote poems and also drew as a child, and he often played outdoors with the many other children who lived in his neighborhood. He also grew up in the company of such family friends as the philosophers William James (1842–1910) and Josiah Royce (1855–1916). He graduated from Harvard University in 1915 and then received an advanced degree from Harvard in 1916.[2] Many of Cummings' summers were spent on Silver Lake in Madison, New Hampshire where his father had built two houses along the eastern shore. The family ultimately purchased the nearby Joy Farm where Cummings' had his primary summer residence.[3]

He exhibited transcendental leanings his entire life. As he grew in maturity and age, Cummings moved more toward an "I, Thou" relationship with God. His journals are replete with references to "le bon Dieu," as well as prayers for inspiration in his poetry and artwork (such as "Bon Dieu! may I some day do something truly great. amen."). Cummings "also prayed for strength to be his essential self ('may I be I is the only prayer—not may I be great or good or beautiful or wise or strong'), and for relief of spirit in times of depression ('almighty God! I thank thee for my soul; & may I never die spiritually into a mere mind through disease of loneliness')."[4]

Cummings wanted to be a poet from childhood and wrote poetry daily aged 8 to 22, exploring assorted forms. He went to Harvard and developed an interest in modern poetry which ignored conventional grammar and syntax, aiming for a dynamic use of language. Upon graduating, he worked for a book dealer.[5]

War years

In 1917, with the First World War ongoing in Europe, Cummings enlisted in the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps, along with his college friend John Dos Passos. Due to an administrative mix-up, Cummings was not assigned to an ambulance unit for five weeks, during which time he stayed in Paris. He fell in love with the city, to which he would return throughout his life.[6]

During their service in the ambulance corps, they sent letters home that drew the attention of the military censors, and were known to prefer the company of French soldiers over fellow ambulance drivers. The two openly expressed anti-war views; Cummings spoke of his lack of hatred for the Germans.[7] On September 21, 1917, just five months after his belated assignment, he and a friend, William Slater Brown, were arrested by the French military on suspicion of espionage and undesirable activities. They were held for 3½ months in a military detention camp at the Dépôt de Triage, in La Ferté-Macé, Orne, Normandy.[6]

They were imprisoned with other detainees in a large room. Cummings' father failed to obtain his son's release through diplomatic channels and in December 1917 wrote a letter to President Wilson. Cummings was released on December 19, 1917, and Brown was released two months later. Cummings used his prison experience as the basis for his novel, The Enormous Room (1922), about which F. Scott Fitzgerald said, "Of all the work by young men who have sprung up since 1920 one book survives—The Enormous Room by e e cummings... Those few who cause books to live have not been able to endure the thought of its mortality."[8]

Cummings returned to the United States on New Year's Day 1918. Later in 1918 he was drafted into the army. He served in the 12th Division at Camp Devens, Massachusetts, until November 1918.[9][10]

Buffalo Bill's

defunct

who used to

ride a watersmooth-silver

stallion

and break onetwothreefourfive pigeonsjustlikethat

Jesus

he was a handsome man

and what i want to know is

how do you like your blueeyed boy

Mister Death

From "Buffalo Bill's" (1920)

Post-war years

Cummings returned to Paris in 1921 and remained there for two years before returning to New York. His collection Tulips and Chimneys came in 1923 and his inventive use of grammar and syntax is evident. The book was heavily cut by his editor. XLI Poems, was then published in 1925. With these collections Cummings made his reputation as an avant garde poet.[5]

During the rest of the 1920s and 1930s Cummings returned to Paris a number of times, and traveled throughout Europe, meeting, among others, Pablo Picasso. In 1931 Cummings traveled to the Soviet Union, recounting his experiences in Eimi, published two years later. During these years Cummings also traveled to Northern Africa and Mexico and worked as an essayist and portrait artist for Vanity Fair magazine (1924–1927).

In 1926, Cummings's parents were in a car accident; only his mother survived, although she was severely injured. Cummings later described the accident in the following passage from his i: six nonlectures series given at Harvard (as part of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures) in 1952 and 1953:

A locomotive cut the car in half, killing my father instantly. When two brakemen jumped from the halted train, they saw a woman standing – dazed but erect – beside a mangled machine; with blood spouting (as the older said to me) out of her head. One of her hands (the younger added) kept feeling her dress, as if trying to discover why it was wet. These men took my sixty-six year old mother by the arms and tried to lead her toward a nearby farmhouse; but she threw them off, strode straight to my father's body, and directed a group of scared spectators to cover him. When this had been done (and only then) she let them lead her away.

His father's death had a profound effect on Cummings, who entered a new period in his artistic life. He began to focus on more important aspects of life in his poetry. He started this new period by paying homage to his father in the poem "my father moved through dooms of love"[11][12]

In the 1930s Samuel Aiwaz Jacobs was Cummings' publisher; he had started the Golden Eagle Press after working as a typographer and publisher.

Final years

In 1952, his alma mater, Harvard University awarded Cummings an honorary seat as a guest professor. The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures he gave in 1952 and 1955 were later collected as i: six nonlectures.

Cummings spent the last decade of his life traveling, fulfilling speaking engagements, and spending time at his summer home, Joy Farm, in Silver Lake, New Hampshire. He died of a stroke on September 3, 1962, at the age of 67 in North Conway, New Hampshire at the Memorial Hospital.[13]

Cummings's papers are held at the Houghton Library at Harvard University and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.[6]

Personal life

Marriages

Cummings was married briefly twice, first to Elaine Orr, then to Anne Minnerly Barton. His longest relationship lasted more than three decades, a common-law marriage to Marion Morehouse.

Cummings's first marriage, to Elaine Orr, began as a love affair in 1918 while she was still married to Scofield Thayer, one of Cummings's friends from Harvard. During this time he wrote a good deal of his erotic poetry.[14] After divorcing Thayer, Elaine married Cummings on March 19, 1924. The couple had a daughter together out of wedlock. However, the couple separated after only two months of marriage and divorced less than nine months later.

Cummings married his second wife Anne Minnerly Barton on May 1, 1929, and they separated three years later in 1932. That same year, Anne obtained a Mexican divorce; it was not officially recognized in the United States until August 1934. Anne died in 1970 aged 72.

In 1934, after his separation from his second wife, Cummings met Marion Morehouse, a fashion model and photographer. Although it is not clear whether the two were ever formally married, Morehouse lived with Cummings in a common-law marriage until his death in 1962. She died on May 18, 1969,[15] while living at 4 Patchin Place, Greenwich Village, New York City, where Cummings had resided since September 8, 1924.[16]

Political views

According to his testimony in EIMI, Cummings had little interest in politics until his trip to the Soviet Union in 1931,[17] after which he shifted rightward on many political and social issues.[18] Despite his radical and bohemian public image, he was a Republican and, later, an ardent supporter of Joseph McCarthy.[19]

Work

Poetry

Despite Cummings's familiarity with avant-garde styles (undoubtedly affected by the Calligrammes of Apollinaire, according to a contemporary observation[20]), much of his work is quite traditional. Many of his poems are sonnets, albeit often with a modern twist, and he occasionally made use of the blues form and acrostics. Cummings' poetry often deals with themes of love and nature, as well as the relationship of the individual to the masses and to the world. His poems are also often rife with satire.

While his poetic forms and themes share an affinity with the Romantic tradition, Cummings' work universally shows a particular idiosyncrasy of syntax, or way of arranging individual words into larger phrases and sentences. Many of his most striking poems do not involve any typographical or punctuation innovations at all, but purely syntactic ones.

i carry your heart with me(i carry it in

my heart)i am never without it(anywhere

i go you go,my dear;and whatever is done

by only me is your doing,my darling)

i fear

no fate(for you are my fate,my sweet)i want

no world(for beautiful you are my world,my true)

and it's you are whatever a moon has always meant

and whatever a sun will always sing is you

From "i carry your heart with me(i carry it in" (1952)[21]

As well as being influenced by notable modernists, including Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound, Cummings in his early work drew upon the imagist experiments of Amy Lowell. Later, his visits to Paris exposed him to Dada and surrealism, which he reflected in his work. He began to rely on symbolism and allegory where he once used simile and metaphor. In his later work, he rarely used comparisons that required objects that were not previously mentioned in the poem, choosing to use a symbol instead. Due to this, his later poetry is "frequently more lucid, more moving, and more profound than his earlier."[22] Cummings also liked to incorporate imagery of nature and death into much of his poetry.

While some of his poetry is free verse (with no concern for rhyme or meter), many have a recognizable sonnet structure of 14 lines, with an intricate rhyme scheme. A number of his poems feature a typographically exuberant style, with words, parts of words, or punctuation symbols scattered across the page, often making little sense until read aloud, at which point the meaning and emotion become clear. Cummings, who was also a painter, understood the importance of presentation, and used typography to "paint a picture" with some of his poems.[23]

The seeds of Cummings' unconventional style appear well established even in his earliest work. At age six, he wrote to his father:

FATHER DEAR. BE, YOUR FATHER-GOOD AND GOOD,

HE IS GOOD NOW, IT IS NOT GOOD TO SEE IT RAIN,

FATHER DEAR IS, IT, DEAR, NO FATHER DEAR,

LOVE, YOU DEAR,

ESTLIN.[24]

Following his autobiographical novel, The Enormous Room, Cummings' first published work was a collection of poems entitled Tulips and Chimneys (1923). This work was the public's first encounter with his characteristic eccentric use of grammar and punctuation.

Some of Cummings' most famous poems do not involve much, if any, odd typography or punctuation, but still carry his unmistakable style, particularly in unusual and impressionistic word order.

anyone lived in a pretty how town

(with up so floating many bells down)

spring summer autumn winter

he sang his didn't he danced his did

Women and men (both little and small)

cared for anyone not at all

they sowed their isn't they reaped their same

sun moon stars rain

From "anyone lived in a pretty how town" (1940)[25]

Cummings' work often does not proceed in accordance with the conventional combinatorial rules that generate typical English sentences (for example, "they sowed their isn't"). His readings of Stein in the early part of the century probably served as a springboard to this aspect of his artistic development. [citation needed] In some respects, Cummings' work is more stylistically continuous with Stein's than with any other poet or writer.[citation needed]

In addition, a number of Cummings' poems feature, in part or in whole, intentional misspellings, and several incorporate phonetic spellings intended to represent particular dialects. Cummings also made use of inventive formations of compound words, as in "in Just"[26] which features words such as "mud-luscious", "puddle-wonderful", and "eddieandbill." This poem is part of a sequence of poems entitled Chansons Innocentes;[27] it has many references comparing the "balloonman" to Pan, the mythical creature that is half-goat and half-man. Literary critic R.P. Blackmur has commented that this usage of language is “frequently unintelligible because he disregards the historical accumulation of meaning in words in favour of merely private and personal associations.”[28]

Many of Cummings' poems are satirical and address social issues[29] but have an equal or even stronger bias toward romanticism: time and again his poems celebrate love, sex, and the season of rebirth.[30]

Cummings also wrote children's books and novels. A notable example of his versatility is an introduction he wrote for a collection of the comic strip Krazy Kat.

Controversy

Cummings is also known for controversial subject matter, as he has a large collection of erotic poetry. In his 1950 collection Xaipe: Seventy-One Poems, Cummings published two poems containing words that caused an outrage in some quarters.[31]

one day a nigger

caught in his hand

a little star no bigger

than not to understand

"i'll never let you go

until you've made me white"

so she did and now

stars shine at night.[32]

and

a kike is the most dangerous

machine as yet invented

by even yankee ingenu

ity(out of a jew a few

dead dollars and some twisted laws)

it comes both prigged and canted[32]

Cummings biographer Catherine Reef notes of the incident:

Friends begged Cummings to reconsider publishing these poems, and the book's editor pleaded with him to withdraw them, but he insisted that they stay. All the fuss perplexed him. The poems were commenting on prejudice, he pointed out, and not condoning it. He intended to show how derogatory words cause people to see others in terms of stereotypes rather than as individuals. "America (which turns Hungarian into 'hunky' & Irishman into 'mick' and Norwegian into 'square- head') is to blame for 'kike,'" he said.[33]

William Carlos Williams spoke out in his defense.[33]

Plays

During his lifetime, Cummings published four plays. HIM, a three-act play, was first produced in 1928 by the Provincetown Players in New York City. The production was directed by James Light. The play's main characters are "Him", a playwright, and "Me", his girlfriend. Cummings said of the unorthodox play:

Relax and give the play a chance to strut its stuff—relax, stop wondering what it is all 'about'—like many strange and familiar things, Life included, this play isn't 'about,' it simply is. . . . Don't try to enjoy it, let it try to enjoy you. DON'T TRY TO UNDERSTAND IT, LET IT TRY TO UNDERSTAND YOU."[34]

Anthropos, or the Future of Art is a short, one-act play that Cummings contributed to the anthology Whither, Whither or After Sex, What? A Symposium to End Symposium. The play consists of dialogue between Man, the main character, and three "infrahumans", or inferior beings. The word anthropos is the Greek word for "man", in the sense of "mankind".

Tom, A Ballet is a ballet based on Uncle Tom's Cabin. The ballet is detailed in a "synopsis" as well as descriptions of four "episodes", which were published by Cummings in 1935. It has never been performed.[35]

Santa Claus: A Morality was probably Cummings's most successful play. It is an allegorical Christmas fantasy presented in one act of five scenes. The play was inspired by his daughter Nancy, with whom he was reunited in 1946. It was first published in the Harvard College magazine the Wake. The play's main characters are Santa Claus, his family (Woman and Child), Death, and Mob. At the outset of the play, Santa Claus's family has disintegrated due to their lust for knowledge (Science). After a series of events, however, Santa Claus's faith in love and his rejection of the materialism and disappointment he associates with Science are reaffirmed, and he is reunited with Woman and Child.

Name and capitalization

Cummings's publishers and others have sometimes echoed the unconventional orthography in his poetry by writing his name in lowercase and without periods (full stops), but normal orthography (uppercase and periods) is supported by scholarship and preferred by publishers today.[36] Cummings himself used both the lowercase and capitalized versions, though he most often signed his name with capitals.[36]

The use of lowercase for his initials was popularized in part by the title of some books, particularly in the 1960s, printing his name in lower case on the cover and spine. In the preface to E. E. Cummings: The Growth of a Writer by Norman Friedman, critic Harry T. Moore notes Cummings "had his name put legally into lower case, and in his later books the titles and his name were always in lower case."[37] According to Cummings's widow, however, this is incorrect.[36] She wrote to Friedman: "You should not have allowed H. Moore to make such a stupid & childish statement about Cummings & his signature." On February 27, 1951, Cummings wrote to his French translator D. Jon Grossman that he preferred the use of upper case for the particular edition they were working on.[38] One Cummings scholar believes that on the rare occasions Cummings signed his name in all lowercase, he may have intended it as a gesture of humility, not as an indication that it was the preferred orthography for others to use.[36]

Adaptations

In 1943, modern dancer and choreographer Jean Erdman presented "The Transformations of Medusa, Forever and Sunsmell" with a commissioned score by John Cage and a spoken text from the titular poem by E. E. Cummings, sponsored by the Arts Club of Chicago. Erdman also choreographed "Twenty Poems" (1960), a cycle of E. E. Cummings's poems for eight dancers and one actor with a commissioned score by Teiji Ito, performed in the round at the Circle in the Square Theatre in Greenwich Village.

In 1961, Pierre Boulez composed "Cummings ist der dichter" from poems by E.E. Cummings.[39]

Aribert Reimann set Cummings to music in "Impression IV" (1961) for soprano and piano.[40]

The Icelandic singer Björk used lines from Cummings's poem "I Will Wade Out" for the lyrics of "Sun In My Mouth" on her 2001 album Vespertine. On her next album, Medúlla (2004), Björk used his poem "It May Not Always Be So" as the lyrics for the song "Sonnets/Unrealities XI."

The 2007 Ra Ra Riot song, "Dying Is Fine," is based on the Cummings' poem dying is fine)but death.

American post-hardcore band La Dispute's first spoken-word/experimental album Here, Hear. includes a song based on Cumming's "somewhere i have never traveled".

The Bloc Party song, "Ion Square", on their album Intimacy, contains lines from Cummings' poem I carry your heart with me.

Singer Nate Ruess speaks the last stanza from "somewhere i have never traveled" in his song "AhHa" from the album Grand Romantic

The American composer Eric Whitacre wrote a cycle of works for choir entitled The City and the Sea, which consists of five poems by Cummings set to music.

Numerous composers have set Cummings' poems to music. Among them are Aki Takase, Dominic Argento, Gary Backlund, William Bergsma, Michael Hedges, Leonard Bernstein, Allen Blank, Marc Blitzstein, John Cage, Romeo Cascarino, Aaron Copland, Serge de Gastyne, David Diamond, John Duke, Brian Fennelly, Margaret Garwood, John Gruen, Daron Hagen, Richard Hundley, Barbara Kolb, Robert Manno, Salvatore Martirano, William Mayer, John Musto, Paul Nordoff, Tobias Picker, Vincent Persichetti, Ned Rorem, Peter Schickele, Elie Siegmeister, Hugo Weisgall, Dan Welcher, Eric Whitacre, and James Yannatos, among many others.[41]

Awards

During his lifetime, Cummings received numerous awards in recognition of his work, including:

- Dial Award (1925)

- Guggenheim Fellowship (1933)

- Shelley Memorial Award for Poetry (1944)

- Harriet Monroe Prize from Poetry magazine (1950)

- Fellowship of American Academy of Poets (1950)

- Guggenheim Fellowship (1951)

- Charles Eliot Norton Professorship at Harvard (1952–1953)

- Special citation from the National Book Award Committee for his Poems, 1923–1954 (1957)

- Bollingen Prize in Poetry (1958)

- Boston Arts Festival Award (1957)

- Two-year Ford Foundation grant of $15,000 (1959)

Books

- The Enormous Room (1922)

- Tulips and Chimneys (1923)

- & (1925) (self-published)

- XLI Poems (1925)

- is 5 (1926)

- HIM (1927) (a play)

- ViVa (1931)

- CIOPW (1931) (art works)

- EIMI (1933) (Soviet travelogue)

- No Thanks (1935)

- Collected Poems (1938)

- 50 Poems (1940)

- 1 × 1 (1944)

- Santa Claus: A Morality (1946)

- XAIPE: Seventy-One Poems (1950)

- i—six nonlectures (1953) Harvard University Press

- Poems, 1923–1954 (1954)

- 95 Poems (1958)

- 73 Poems (1963) (posthumous)

- Fairy Tales (1965)

- Etcetera: The Unpublished Poems (1983)

- Complete Poems, 1904–1962, edited by George James Firmage, Liveright 2008

See also

Notes

- ^ "E. E. Cummings' Life". www.english.illinois.edu. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "E. E. Cummings Biography - life, family, children, story, death, wife, mother, book, old, information, born". Notablebiographies.com. September 3, 1962. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- ^ Sawyer-Lauçanno, Christopher (January 1, 2004). "E.E. Cummings: A Biography". Sourcebooks, Inc. – via Google Books.

- ^ "E. E. Cummings: Poet And Painter".

- ^ a b "E. E. Cummings". November 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c "E. E. Cummings: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center". Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ Friedman, Norman "Cummings, E[dward] E[stlin]" in Steven Serafin The Continuum Encyclopedia of American Literature, 2003, Continuum, p. 244.

- ^ Bloom, p. 1814.

- ^ Kennedy, p. 186.

- ^ "Data on U.S. Army Divisions during World War I, WWI, The Great War".

- ^ "My father moved through dooms of love".

- ^ Lane, Gary (1976). I Am: A Study of E. E. Cummings' Poems. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. pp. 41–43. ISBN 0-7006-0144-9.

- ^ "E. E. Cummings Dies of Stroke. Poet Stood for Stylistic Liberty". New York Times. September 4, 1962.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Selected Poems, Ed. Richard S. Kennedy, Liveright, 1994.

- ^ Marion Morehouse Cummings, Poet's Widow, Top Model, Dies , The New York Times, May 19, 1969.

- ^ Sawyer-Lauçanno, p. 255.

- ^ Carla Blumenkranz, "The Enormous Poem: When E.E. Cummings Repunctuated Stalinism." Poetry Foundation. www.poetryfoundation.org/

- ^ [http://college.cengage.com/english/lauter/heath/4e/students/author_pages/modern/cummings_ee.html "Heath Anthology of American Literaturee.e.�cummings - Author Page"].

{{cite web}}: replacement character in|title=at position 43 (help) - ^ Wetzsteon, Ross. 'Republic of Dreams: Greenwich Village: The American Bohemia, 1910–1960', pp. 449 Google Books

- ^ Taupin, Rene, The Influence of French Symbolism on Modern American Poetry 1927 (Trans. William Pratt), AMS Inc, New York 1985 ISBN 0404615791

- ^ "i carry your heart with me(i carry it in" at the Poetry Foundation.

- ^ Friedman, Norman. E. E. Cummings the Art of His Poetry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1967. p. 89.

- ^ Landles, Iain (2001). "An Analysis of Two Poems by E. E. Cummings". SPRING, the Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society. 10: 31–43.

- ^ Selected letters of E. E. Cummings, (1972) Edward Estlin Cummings, Frederick Wilcox Dupee, George Stade. University of Michigan p3 ISBN 978-0-233-95637-4

- ^ "anyone lived in a pretty how town" at the Poetry Foundation

- ^ "in Just".

- ^ Chansons Innocentes

- ^ Friedman, Norman. E. E. Cummings the Art of His Poetry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1967. p. 61-62.

- ^ "why must itself up every of a park"

- ^ "anyone lived in a pretty how town"

- ^ Friedman, Norman, and Harry Thornton Moore. E. E. Cummings the Growth of a Writer. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1964. p 153-54.

- ^ a b Cummings, Xaipe, Seventy-one Poems. New York: Oxford UP, 1950.

- ^ a b E. Cummings (2006) by Catherine Reef, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt p115 ISBN 978-0-618-56849-9

- ^ Kennedy, p. 295.

- ^ GVSU.edu The E. E. Cummings Society.

- ^ a b c d Friedman, Norman (1992). "Not "e. e. cummings"". Spring. 1: 114–121. Retrieved December 13, 2005.

- ^ Friedman, Norman (1964). E. E. Cummings: The Growth of a Writer. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-0978-5.

- ^ Friedman, Norman (1995). "Not "e. e. cummings" Revisited". Spring. 5: 41–43. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ "cummings ist der dichter, Pierre Boulez".

- ^ Reimann, Aribert; Cummings, E. E. (Edward Estlin). "Impression IV : nach einem Gedicht von E.E. Cummings : four Singstimme und Klavier (1961) / Aribert Reimann. music" – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "E.E. Cummings settings", RecMusic

References

- Bloom, Harold, Twentieth-century American literature, New York : Chelsea House Publishers, 1985–1988. ISBN 978-0-87754-802-7.

- Cohen, Milton A. (1987). POETandPAINTER: The Aesthetics of E. E. Cummings' Early Work. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1845-4.

- Friedman, Norman (editor), E. E. Cummings: A Collection of Critical Essays. ISBN 978-0-9829733-0-1

- Friedman, Norman, E. E. Cummings: The Art of his Poetry.

- Galgano, Andrea, La furiosa ricerca di Edward E. Cummings, in Mosaico, Roma, Aracne, 2013, pp. 441–444 ISBN 978-88-548-6705-5

- Heusser, Martin. I Am My Writing: The Poetry of E.E. Cummings. Tübingen: Stauffenburg, 1997.

- Hutchinson, Hazel. The War That Used Up Words: American Writers and the First World War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015.

- James, George, E. E. Cummings: A Bibliography.

- Kennedy, Richard S. (October 17, 1994) [1980]. Dreams in the Mirror (2nd ed.). New York: Liveright. ISBN 0-87140-155-X.

- McBride, Katharine, A Concordance to the Complete Poems of E.E.Cummings.

- Mott, Christopher. "The Cummings Line on Race." Spring: The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society, vol. 4, pp. 71–75, Fall 1995.

- Norman, Charles, E. E. Cummings: The Magic-Maker, Boston, Little Brown, 1972.

- Sawyer-Lauçanno, Christopher, E. E. Cummings: A Biography, Sourcebooks, Inc. (2004) ISBN 978-1-57071-775-8.

External links

- Works by E. E. Cummings at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about E. E. Cummings at the Internet Archive

- Works by E. E. Cummings at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- E. E. Cummings, Lifelong Unitarian Biography of Cummings and his relationship with Unitarianism

- E.E. Cummings Personal Library at LibraryThing

- Papers of E. E. Cummings at the Houghton Library at Harvard University

- E. E. Cummings Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Poems by E. E. Cummings at PoetryFoundation.org

- Jonathan Yardley, E. E. Cummings: A Biography, Sunday, October 17, 2004, Page BW02, The Washington Post Book Review

- SPRING:The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society

- Modern American Poetry

- E. E. Cummings at Library of Congress Authorities — with 202 catalog records

- Biography and poems of E. E. Cummings at Poets.org

- 1894 births

- 1962 deaths

- American Christians

- American male poets

- American Unitarians

- Formalist poets

- Guggenheim Fellows

- Harvard University alumni

- Massachusetts culture

- Massachusetts Republicans

- Modernist poets

- Modernist writers

- Writers from Cambridge, Massachusetts

- People from Carroll County, New Hampshire

- People from Greenwich Village

- Sonneteers

- Poets from Massachusetts

- Analysands of Fritz Wittels

- Self-published authors

- Bollingen Prize recipients

- Burials at Forest Hills (Jamaica Plain)

- 20th-century American poets

- American anti-communists