Eitaro Ishigaki

Eitaro Ishigaki | |

|---|---|

石垣 栄太郎 | |

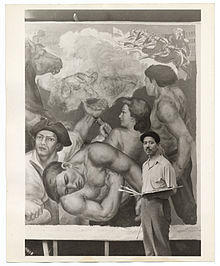

Eitaro Ishigaki, c. 1940, from the Archives of American Art | |

| Born | December 1, 1893 Taiji, Wakayama, Japan |

| Died | January 23, 1958 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting, muralist |

| Spouse | Ayako Ishigaki |

Eitaro Ishigaki (石垣 栄太郎, Ishigaki Eitarō, born on December 1, 1893, died on January 23, 1958) was a Japanese-born American painter.[1] He lived and worked in the United States between 1909 and 1952.[2]: 39–40 Ishigaki, who came to the US as a migrant worker in the early 20th century, depicted the contradictions of American society from the perspective of a minority person.[3] Ishigaki was also a founding member of progressive and politically active organizations, including the John Reed Clubs (JRC) in 1929 and the American Artists' Congress in 1936.[2]: 40 Ishigaki was a committed leftist throughout his life and career, "whose canvases and murals depicted social injustices and urban life."[4]: 2 His one of best known works, The Bonus March (1932), depicts a critical moment in WWI veterans' famous march into Washington, D.C., in 1932.[5]: 9

Ishigaki's work is held by the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1997 and 2013, the Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama held commemorative exhibitions of his works. His work is also located in the Ishigaki Eitaro Memorial Museum in Wakayama, Japan.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early years on the US West Coast (1909–1915)

[edit]Eitaro Ishigaki was born on December 1, 1893, in Taiji, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan. In 1909, at the age of 16, he emigrated to the United States in to live with his father, who had emigrated to the United States in 1901. Many people from Wakayama Prefecture, mainly from the Kinan region, emigrated to the United States. Among them were Ishigaki, Seimatsu Hamaji and Henry Sugimoto, who became painters in the United States.[6] According to the short biography in the anthology Asian American Art, 1850-1970, Ishigaki arrived with his father in Seattle and moved with him to Bakersfield, California, the following year.[1]: 338 Like the majority of Asian immigrants on the US West Coast, Ishigaki experienced life in the United States at that time as a migrant worker who had to do underpaid and physically strenuous work. For example, he worked as a day laborer on orchards, an assistant (busboy) in restaurants and as a cleaner in hotels in Bakersfield, San Francisco, and Seattle.[2]: 45

In Bakersfield, Ishigaki came into contact with socialism for the first time.[1]: 338 However, Ishigaki's deeper confrontation with socialism and communism did not take place until he moved to San Francisco in 1912.[2]: 45 In the spring of 1914, Ishigaki met Sen Katayama in San Francisco. Katayama was a pioneer of the Japanese workers' movement and participated in the founding of the first Social Democratic Party of Japan, the Communist Party of Japan, as well as the Communist Party USA. During his third stay in the United States, Katayama was considered an influential activist in small circles of Japanese immigrants in San Francisco and New York.[2]: 45 Subsequently, Katayama became a mentor for Ishigaki. According to Ishigaki, he met Katayama and a small circle of Japanese immigrants, which included Unzō Taguchi and Tsunao Inomata, as a form of intellectual support for the Russian Revolution, and they discussed, for example, Lenin's writing The State and Revolution. Katayama advised Ishigaki to return to Japan to set up schools there to propagate Leninism and thus become a leader of the revolution. However, he did not comply with this request.[2]: 47

Simultaneously, Ishigaki began his artistic training in San Francisco: in 1913 he attended the William Best School of Art and in 1914 the San Francisco Institute of Art.[1] He met the poet Takeshi Kanno and his wife, the sculptor Gertrude Boyle Kanno, through whom he gained contact with artists and writers such as Joaquin Miller.[1]: 338 When Gertrud Boyle Kanno left her husband in 1915 and moved to New York City, the seventeen-years-younger Ishigaki followed her.[2]: 48

Leftist artist and activist in New York City (1915–1951)

[edit]Gertrude Boyle Kanno and Ishigaki lived in New York in the Greenwich Village district, to which her husband followed them, securing a residence nearby. The triangular relationship between the American sculptor and the two Japanese immigrants was a scandal. In 1929, the Kannos reconciled. In January 1927, the women's rights activist and author Ayako Tanaka visited Ishigaki in his apartment on Horatio Street, where his works impressed her. Tanaka had emigrated to the United States in 1926 after being imprisoned in Japan for her work as an activist, with her sister. Tanaka moved to New York despite the opposition from her family and married Ishigaki in 1931. In August 1932, the Ishigakis had a daughter, but she died after ten days. When Ayako Ishigaki published her autobiography Restless Wave in 1940 under the pseudonym Haru Matsui, the book contained illustrations made by her husband.[2]: 50

In New York, Ishigaki continued his art studies, attending John Sloan's evening class at the Arts Student League and eventually completing his studies there in 1918. Ishigaki was part of a network of Japanese emigre artists in New York, with whom he exhibited together. In 1922 he was part of the Exhibition of Paintings and Sculptures by the Japanese Artists Society of New York City in the Civic Club, today's New York Estonian House. Then, in 1927, he showed works in The First Annual Exhibition of Paintings and Sculptures by Japanese Artists in New York.[1]: 338

Ishigaki was involved in several projects within the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).[7][1]: 338 In this context, from 1936, he created two murals in the Harlem Courthouse with the titles The Spirit of 1776 and Emancipation of Negro Slaves, which showed America's independence and the liberation of slaves and were controversially discussed. Among other things, the skin color of Abraham Lincoln was perceived as too dark, and the facial expression of George Washington was also criticized.[8][2]: 66 This kind of criticism was racially based, directed as much at the creator himself as the painting.[2]: 66 Because the presentation of his controversial paintings in 1938 had led to considerable criticism, the New York City Council ruled his murals offensive and they were eventually destroyed in 1941.[9] While Ishigaki was still working on the murals in the Harlem Courthouse, he was fired from the Federal Art Project together with other emigre artists in July 1937 because they were not American citizens. Later Ishigaki stated: "I have lived in this country for thirty years, but because Orientals cannot become citizens, they have taken our only means of livelihood from us. Though we live like other Americans—have been educated here, pay taxes, and have the same stomachs as American citizens—we are not allowed to become naturalized. You can see how unfair the whole thing is."[2]: 60 Ishigaki created politically engaged paintings that dealt with the struggle of the workers for their rights and racism in the United States. They were regularly exhibited in the 1920s, but only sporadically in the 1930s and 1940s. In the 1930s, Ishigaki was active in the American Artists' Congress, in whose exhibitions he showed works from 1936 to 1940. In 1936 he also exhibited at the Exhibition by Japanese Artists in New York in the ACA Gallery, which also showed Ishigaki's solo exhibitions in the same year and 1940.[1]: 338 His painting, Man on the Horse (1932), depicted a plain-clothed Chinese guerrilla confronting the Japanese army, heavily equipped with airplanes and warships. His other painting, Flight (1937), depicted two Chinese women escaping Japanese bombing, running with three children past one man lying dead on the ground.[10]

In addition to his studies, Ishigaki was involved in a communist gathering led by the Japanese political activist Sen Katayama. Ishigaki already knew Katayama since they met in San Francisco in 1914. In 1929 Ishigaki was a founding member of the communist group John Reed Clubs, which included John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway. During this time, he also met the Mexican artists Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo and José Clemente Orozco. Under these influences, the style of his works, which have long reflected social issues, developed towards the sculptural modelling of forms that can be found in Rivera's murals.[1]: 338 Ishigaki regularly exhibited in exhibitions of the John Reed Clubs and was positively received by the critics there.[2]: 62 From July 1929, Ishigaki published several of his works in the Marxist magazine New Masses, which was closely linked to the Communist Party USA. His first contribution was a reproduction of his painting Undefeated Arm on the cover. Other illustrations of him included Fight, also depicted on the cover in June 1932, and South U.S.A. (Ku Klux Klan) as an illustration of a report on a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan in Atlanta and Down with the Swastika, both of which were used in 1936.[2]: 56 New Masses offered left-wing artists a venue for their socially engaged works. In the context of the magazine, artists were able to discuss the relationship between their art and the political concerns. However, the magazine's editor, Mike Gold, increasingly focused the magazine on the enforcement of workers' concerns through a more explicit political orientation of the content from June 1928 on, and as a result proletarian realism increasingly prevailed in the publication's art features. In this context Ishigaki also adapted his work.[2]: 57 In March 1936, a reproduction of Ishigaki's painting South U.S.A. also appeared in the Daily Worker. Ishigaki’s K.K.K. (Ku-Klux-Klan) was positioned to illustrate an article by Dorothy Calhoun about her visit to two mothers of the Scottsboro Boys, victims of racism in the American judicial system.[2]: 62

During World War II, Ishigaki and Ayako Ishigaki worked for the United States Office of War Information.[11] However, following the war, the Ishigakis were affected by the anti-communist McCarthy wave: in 1950, Ishigaki and Ayako Ishigaki were investigated several times by the Federal Bureau of Investigation because of their contacts with Agnes Smedley, who was accused of being a spy for the Soviet Union. In this context, the two also learned that their activities of the previous decades had been monitored by the United States government. Subsequently, the Ishigakis feared their arrests. Because of this, they did not participate in the commemorative event at the Friends Meeting House for Agnes Smedley on May 18, 1950. In 1951, Ishigaki left the country together with Ayako Ishigaki and returned to Japan.[7][1]: 338

Last years in Japan (1951–1958)

[edit]In Japan, Ishigaki settled with his wife in Tokyo, where he was not welcome. According to Ayako Ishigaki, he was isolated and lost his enthusiasm for painting. In the years 1955 to 1958, Ishigaki exhibited as part of the exhibition Ten Ten Kai in Tokyo. Ishigaki died on January 23, 1958, in Tokyo. The following year, the Tokyo gallery Bungei Shunjū showed a retrospective.[1]: 338 In his home town of Taiji, Wakayama Prefecture, there is the Taiji Town Ishigaki Memorial Museum (opened in 1991), built with private funds by his wife Ayako Ishigaki after Ishigaki's death.[12] Later the building and its collection was donated to Taiji Town in 2002.

Further reading

[edit]- Handel-Bajema, Ramona. Art Across Borders: Japanese Artists in the United States before World War II, Portland: MerwinAsia, 2021.[4]

- Hemingway, Andrew. Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926-1956, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

- Wang, ShiPu. "By Proxy of His Black Hero: 'The Bonus March' (1932) and Eitarō Ishigaki's Critical Engagement in American Leftist Discourses." American Studies 51, no. 3/4 (Fall/Winter 2010): 7–30.[5]

- Wang, ShiPu. The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa, University Park: Penn State University Press, 2017.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gordon H. Chang; Mark Dean Johnson; Paul J. Karlstrom; Sharon Spain, eds. (2008). Asian American art, 1850-1970. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5752-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wang, ShiPu (2017). The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- ^ "(美の履歴書:735)「ボーナス・マーチ」 石垣栄太郎 悲劇の中に見た希望とは:朝日新聞デジタル". 朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). 2022-02-22. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b Handel-Bajema, Ramona (2021). Art Across Borders: Japanese Artists in the United States before World War II. Portland: MerwinAsia.

- ^ a b ShiPu, Wang. "By Proxy of His Black Hero: "The Bonus March" (1932) and Eitarō Ishigaki's Critical Engagement in American Leftist Discourses". American Studies. 51 (3/4 (Fall/Winter 2010)): 7–30.

- ^ "生誕120年記念 石垣栄太郎展". 和歌山県立近代美術館 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b Japanese Artists In New York Between The World Wars

- ^ The American Scene Art of the 1930s and 1940s, Harlem Courthouse Mural study

- ^ Race, ethnicity and migration in modern Japan / edited by Michael Weiner. London: Routledge, 2004, p. 333.

- ^ Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan: Imagined and imaginary minorities Page 333

- ^ Michael Denning (1998). The cultural front: the laboring of American culture in the Twentieth Century. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-170-9.

- ^ "太地町立石垣記念館|太地町観光協会(和歌山県)". 太地町立石垣記念館|太地町観光協会(和歌山県) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- 1893 births

- 1958 deaths

- Federal Art Project artists

- American muralists

- American artists of Japanese descent

- Japanese emigrants to the United States

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- People of the United States Office of War Information

- People from Wakayama Prefecture

- People deported from the United States

- Artists from Wakayama Prefecture

- 20th-century American male artists