Epiglottis

| Epiglottis | |

|---|---|

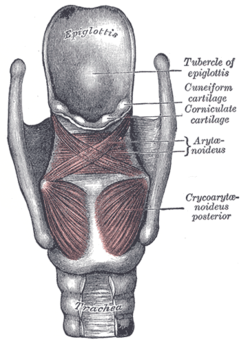

Posterior view of the larynx. The epiglottis is the most superior structure shown. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Hypopharyngeal eminence[1][unreliable source?] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Epiglottis |

| MeSH | D004825 |

| TA98 | A06.2.07.001 |

| TA2 | 3190 |

| FMA | 55130 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The epiglottis is a flap made of elastic cartilage tissue covered with a mucous membrane, attached to the entrance of the larynx. It projects obliquely upwards behind the tongue and the hyoid bone, pointing dorsally. It stands open during breathing, allowing air into the larynx. During swallowing, it closes to prevent aspiration, forcing the swallowed liquids or food to go down the esophagus instead. It is thus the valve that diverts passage to either the trachea or the esophagus.

The epiglottis gets its name from being above the glottis (epi- + glottis). There are taste buds on the epiglottis.[2]

Structure

The epiglottis is shaped somewhat like a leaf of purslane, with the stem attached to the anterior part of the thyroid cartilage.[3]

The epiglottis is one of nine cartilaginous structures that make up the larynx (voice box). During breathing, it lies completely within the larynx. During swallowing, it serves as part of the anterior of the pharynx.[citation needed]

Histology

In a direct section of the epiglottis it can be seen that the body consists of elastic cartilage. The epiglottis has two surfaces, a lingual and a laryngeal surface, related to the oral cavity and the larynx respectively.

The entire lingual surface and the apical portion of the laryngeal surface (since it is vulnerable to abrasion due to its relation to the digestive tract) are covered by stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium. The rest of the laryngeal surface on the other hand, which is in relation to the respiratory system, has respiratory epithelium: pseudostratified, ciliated columnar cells and mucus secreting goblet cells.

Development

The epiglottis arises from the fourth pharyngeal arch. It can be seen as a distinct structure later than the other cartilage of the pharynx, visible around the fifth month of development.[4]

Function

The epiglottis is normally pointed upward during breathing with its underside functioning as part of the pharynx. During swallowing, elevation of the hyoid bone draws the larynx upward; as a result, the epiglottis folds down to a more horizontal position, with its superior side functioning as part of the pharynx. In this manner, the epiglottis prevents food from going into the trachea and instead directs it to the esophagus, which is at the back. Should food or liquid enter the windpipe due to the epiglottis failing to close properly, the gag reflex is induced to protect the respiratory system.

Gag reflex

The glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) sends fibers to the upper epiglottis that contribute to the afferent limb of the gag reflex. (The gag reflex is variable in people from a limited to a hypersensitive response.) The superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X) sends fibers to the lower epiglottis that contribute to the efferent limb of the cough reflex.[5] This initiates an attempt to try to dislodge the food or liquid from the windpipe.

Speech sounds

In some languages, the epiglottis is used to produce epiglottal consonant speech sounds, though this sound-type is rather rare.

Clinical significance

Inflammation

Inflammation of the epiglottis is known as epiglottitis. Epiglottitis is mainly caused by Haemophilus influenzae. A person with epiglottitis may have a fever, sore throat, difficulty swallowing, and difficulty breathing. For this reason, in children, acute epiglottitis is considered a medical emergency, because of the risk of obstruction of the pharynx. Epiglottitis is often managed with antibiotics, racemic epinephrine (a sympathomimetic bronchodilator that is delivered by aerosol), and may require tracheal intubation or a tracheostomy if breathing is difficult.[6]Behind the root of the tongue is an epiglottic vallecula which is an important anatomical landmark in intubation.

The incidence of epiglottitis has decreased significantly in countries where vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae is administered.[7][8]

History

The epiglottis was first described by Aristotle, although the epiglottis' function was first defined by Vesalius in 1543. It also has Greek roots.[9]

Additional images

-

Epiglotic cartilage.

-

Larynx

-

Cut through the larynx of a horse

-

The cartilages of the larynx. Posterior view.

-

Ligaments of the larynx. Posterior view.

-

Coronal section of larynx and upper part of trachea.

-

The entrance to the larynx, viewed from behind.

-

Muscles of larynx. Side view. Right lamina of thyroid cartilage removed.

-

Sagittal section of nose mouth, pharynx, and larynx.

-

Larynx. 1=vocal folds, 2=vestibular fold, 3=epiglottis, 4=plica aryepiglottica, 5=arytenoid cartilage, 6=sinus piriformis, 7=dorsum of the tongue

See also

References

- ^ Stevenson, Roger E. (2006). Human malformations and related anomalies. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516568-3.

- ^ Jowett, Shrestha, 1998. Mucosa and taste buds of the human epiglottis. Journal of Anatomy 193(Pt 4): 617–618. [Link]

- ^ Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 951. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^ Schoenwolf, Gary C. (2009). ""Development of the Urogenital system"". Larsen's human embryology (4th ed., Thoroughly rev. and updated. ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 362. ISBN 9780443068119.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ April, Ernest. Clinical Anatomy, 3rd ed. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins.

- ^ Nicki R. Colledge; Brian R. Walker; Stuart H. Ralston, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. illustrated by Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 681. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^ Reilly, Brian; Reddy, Srijaya K.; Verghese, Susan T. (Oct 2012). "Acute epiglottitis in the era of post-Haemophilus influenzae type B (HIB) vaccine". Journal of Anesthesia. 27 (2): 316–7. doi:10.1007/s00540-012-1500-9. PMID 23076559. Retrieved Nov 15, 2014.

- ^ Hermansen, MN; Schmidt, J. H.; Krug, A. H.; Larsen, K; Kristensen, S (Apr 2014). "Low incidence of children with acute epiglottis after introduction of vaccination". Dan Med J. 61 (4): A4788. PMID 24814584. Retrieved Nov 15, 2014.

- ^ Lydiatt, Daniel D.; Bucher, Gregory S. (2010). "The historical Latin and etymology of selected anatomical terms of the larynx". Clinical Anatomy: NA. doi:10.1002/ca.20912.

External links

- lesson11 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (larynxsagsect)