Epsilon Boötis

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Boötes |

| Right ascension | 14h 44m 59.21746s[1] |

| Declination | +27° 04′ 27.2099″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 2.37[2] / 5.12[3] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | K0 II-III[4] + A2 V[5] |

| U−B color index | +0.73[2] |

| B−V color index | +0.97[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | -16.31[6] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: -50.95[1] mas/yr Dec.: +21.07[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 16.10 ± 0.66 mas[1] |

| Distance | 203 ± 8 ly (62 ± 3 pc) |

| Details | |

| A | |

| Mass | 4.6[7] M☉ |

| Radius | 33[6] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 501[6] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 2.2[6] cgs |

| Temperature | 4,550[6] K |

| Metallicity | –0.13[6] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 10.9[6] km/s |

| Age | 37.4 ± 4.2[8] Myr |

| B | |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 123[9] km/s |

| Other designations | |

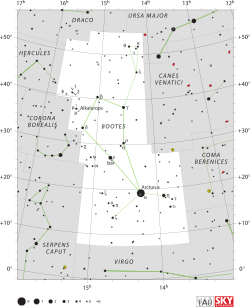

Epsilon Boötis (ε Boötis, abbreviated Epsilon Boo, ε Boo), also named Izar,[12] is a binary star in the northern constellation of Boötes. The star system can be viewed with the unaided eye at night, but resolving the pair with a small telescope is challenging; an aperture of 76 mm (3.0 in) or greater is required.[13]

Nomenclature

ε Boötis (Latinised to Epsilon Boötis) is the star's Bayer designation.

It bore the traditional names Izar, Mirak and Mizar, and was named Pulcherrima by Otto Struve.[14] Izar, Mirak and Mizar are derived from the Arabic إزار ’izār meaning 'veil' and المراق al-maraqq meaning 'the loins'; 'Pulcherrima' is Latin for 'loveliest'.[15] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[16] to catalogue and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN approved the name Izar for this star on 21 August 2016 and it is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[12]

In the catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, this star was designated Mintek al Aoua (منطقة العوّاء - minṭáqa al awwa), which was translated into Latin as Cingulum Latratoris, meaning belt of barker.[17]

In Chinese, 梗河 (Gěng Hé), meaning Celestial Lance, refers to an asterism consisting of Epsilon Boötis, Sigma Boötis and Rho Boötis.[18] Consequently, Epsilon Boötis itself is known as 梗河一 (Gěng Hé yī, Template:Lang-en.)[19]

Properties

Epsilon Boötis consists of a pair of stars with an angular separation of 2.852 ± 0.014 arcseconds at a position angle of 342.°9 ± 0.°3.[20] The brighter component (A) has an apparent visual magnitude of 2.37,[2] making it readily visible to the naked eye at night. The fainter component (B) is at magnitude 5.12,[3] which by itself would also be visible to the naked eye. Parallax measurements from the Hipparcos astrometry satellite[21][22] put the system at a distance of about 203 light-years (62 parsecs) from the Earth.[1] This means the pair has a projected separation of 185 Astronomical Units and they orbit each other with a period of at least 1,000 years.[15]

The brighter member has a stellar classification of K0 II-III,[4] which means it is a fairly late-stage star well into its stellar evolution, having already exhausted its supply of hydrogen fuel at the core. With more than four times the mass of the Sun,[7] it has expanded to about 33 times the Sun's radius and is emitting 501 times the luminosity of the Sun.[6] This energy is being radiated from its outer envelope at an effective temperature of 4,550 K,[6] giving it the orange hue of a K-type star.[23]

The companion star has a classification of A2 V,[5] so it is a main sequence star that is generating energy through the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen at its core. This star is rotating rapidly, with a projected rotational velocity of 123 km s−1[9] By the time the smaller main sequence star reaches the current point of the primary in its evolution, the larger star will have lost much of its mass in a planetary nebula and will have evolved into a white dwarf. The pair will have essentially changed roles: the brighter star becoming the dim dwarf, while the lesser companion will shine as a giant star.[15]

In culture

In one Star Trek episode Whom Gods Destroy the major character Kelvar Garth is also referred to as Garth of Izar.

In 1973, the Scottish astronomer and science fiction writer Duncan Lunan claimed to have managed to interpret a message caught in the 1920s by two Norwegian physicists[24] that, according to his theory, came from a probe orbiting the Moon and sent there by the inhabitants of a planet orbiting Epsilon Boötis.[25] The story was even reported in Time magazine.[26] Lunan later withdrew his Epsilon Boötis theory, presenting proofs against it and clarifying why he was brought to formulate it in the first place but would later go on to revoke his withdrawal.[27]

References

- ^ a b c d e f van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, H. L.; et al. (1966). "UBVRIJKL photometry of the bright stars". Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. 4 (99). Bibcode:1966CoLPL...4...99J.

- ^ a b c "HR 5506 -- Star in double system", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2012-01-09

- ^ a b Luck, R. Earle; Wepfer, Gordon G. (November 1995), "Chemical Abundances for F and G Luminosity Class II Stars", Astronomical Journal, 110: 2425, Bibcode:1995AJ....110.2425L, doi:10.1086/117702

- ^ a b Cowley, A.; et al. (April 1969), "A study of the bright A stars. I. A catalogue of spectral classifications", Astronomical Journal, 74: 375–406, Bibcode:1969AJ.....74..375C, doi:10.1086/110819

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Massarotti, Alessandro; et al. (January 2008), "Rotational and Radial Velocities for a Sample of 761 Hipparcos Giants and the Role of Binarity", The Astronomical Journal, 135 (1): 209–231, Bibcode:2008AJ....135..209M, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/1/209

- ^ a b Gondoin, P. (December 1999), "Evolution of X-ray activity and rotation on G-K giants", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 352: 217–227, Bibcode:1999A&A...352..217G

- ^ Tetzlaff, N.; Neuhäuser, R.; Hohle, M. M. (January 2011), "A catalogue of young runaway Hipparcos stars within 3 kpc from the Sun", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 410 (1): 190–200, arXiv:1007.4883, Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410..190T, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17434.x

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Royer, F.; et al. (October 2002), "Rotational velocities of A-type stars in the northern hemisphere. II. Measurement of v sin i", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 393: 897–911, arXiv:astro-ph/0205255, Bibcode:2002A&A...393..897R, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020943

- ^ "CCDM J14449+2704AB", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2012-01-09

- ^ "HR 5505 -- Star in double system", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2012-01-09

- ^ a b "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Monks, Neale (2010), Go-To Telescopes Under Suburban Skies, Patrick Moore's Practical Astronomy Series, Springer, ISBN 1-4419-6850-4

- ^ Norton's Star Atlas, publ. Gall & Inglis, Edinburgh, 2nd Ed., 1959

- ^ a b c Kaler, James B., "Izar", Stars, University of Illinois, retrieved 2012-01-09

- ^ "IAU working group on star names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Knobel, E. B. (June 1895), "Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, on a catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Mohammad Al Achsasi Al Mouakket", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 55: 429, Bibcode:1895MNRAS..55..429K, doi:10.1093/mnras/55.8.429

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Template:Zh icon 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ^ Template:Zh icon 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表, Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 23, 2010.

- ^ Prieur, J.-L.; et al. (June 2008), "Speckle observations with PISCO in Merate - V. Astrometric measurements of visual binaries in 2006", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 387 (2): 772–782, Bibcode:2008MNRAS.387..772P, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13265.x

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Perryman, M. A. C.; Lindegren, L.; Kovalevsky, J.; et al. (July 1997), "The Hipparcos Catalogue", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 323: L49–L52, Bibcode:1997A&A...323L..49P

- ^ Perryman, Michael (2010), The Making of History's Greatest Star Map, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11602-5

- ^ "The Colour of Stars", Australia Telescope, Outreach and Education, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, December 21, 2004, retrieved 2012-01-16

- ^ Holm, Sverre (March 16, 2004), The Five Most Likely Explanations for Long Delayed Echoes, retrieved 2009-09-01

- ^ "Spaceprobe from Epsilon Bootes" by Duncan Lunan, in "Spaceflight" (British Interplanetary Society), 1973

- ^ "Message from a Star", Time, April 9, 1973, retrieved 2009-08-27

- ^ Lunan, Duncan (March 1998), "Epsilon Boötis Revisited", Analog Science Fiction and Fact, 118 (3)