Eugene Bullard

Eugene Jacques Bullard | |

|---|---|

Bullard in his uniform as a caporal | |

| Nickname(s) | Black Swallow of Death (l'Hirondelle noire de la mort) |

| Born | October 9, 1895 Columbus, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | October 12, 1961 (aged 66) New York City, U.S. |

| Buried | 40°45′6″N 73°47′58″W / 40.75167°N 73.79944°W |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | 170th French Infantry Regiment |

| Years of service | 1914–1919, 1940 |

| Battles / wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Légion d'honneur Médaille militaire Croix de guerre Croix de guerre Croix du combattant volontaire 1914–1918 Insigne des blessés militaires Médaille Interalliée 1914–1918 Médaille commémorative de la guerre 1914–1918 Médaille commémorative de la guerre 1939–1945 Insignia for the Military Wounded |

Eugene Jacques Bullard (October 9, 1895 – October 12, 1961), born Eugene James Bullard, was the first African-American military pilot.[1] His life has been surrounded by many legends.[2] However, Bullard, who flew for France, was unquestionably one of the few black combat pilots during World War I, along with William Robinson Clarke, a Jamaican who flew for the Royal Flying Corps and Ahmet Ali Çelikten of the Ottoman Empire.

Early life

Bullard was born in Columbus, Georgia, the seventh of 10 children born to William (Octave) Bullard, a black man from Martinique, and Josephine ("Yokalee") Thomas, an indigenous Creek woman.[3] His father's ancestors had been enslaved in Haiti by French refugees who later fled during the Haitian Revolution, which abolished slavery.[4] Bullard's ancestors left the Caribbean for the United States and took refuge with the Creek Indians.[5][6][7][8]

Bullard was a student at the Twenty-eighth Street School from 1901 to 1906.[9]

As a teenager, he stowed away on the German freighter Marta Russ,[10] hoping to escape racial discrimination. (He later said that he witnessed his father's narrow escape from lynching). Bullard arrived at Aberdeen and made his way south to Glasgow. In London, he boxed and performed slapstick in the Freedman Pickaninnies, an African-American troupe.[10] On a visit to Paris, he decided to settle in France. He boxed in Paris and also worked in a music hall.

World War I

Marching Regiment of the Foreign Legion

World War I began in August 1914, and on October 19, 1914, Bullard enlisted and was assigned to the 3rd Marching Regiment of the Foreign Legion (R.M.L.E.),[11] as foreign volunteers were allowed only to serve in the French Foreign Legion.[12]

By 1915, Bullard was a machine gunner and saw combat on the Somme front in Picardy. In May and June, he was at Artois, and in the fall of that year fought in a second Champagne offensive (September 25 – November 6, 1915) along the Meuse River.[13][14] He was assigned to the 3rd Marching Regiment of the 1st Foreign Regiment. On July 13, he joined the 2nd Marching Regiment of the 1st Foreign Regiment and also served with the 170th French Infantry Regiment (Template:Lang-fr), known as the "hirondelles noires de la mort" ("black swallows of death"). The 2nd Marching Regiment of the 1st Foreign Regiment and the 2nd Marching Regiment of the 2nd Foreign Regiment were serving as part of the 1st Moroccan Division. Commanded initially by Hubert Lyautey, Resident-General of Morocco at the outbreak of World War I, the division was a mix of the Metropolitan and Colonial French troops, including Legionnaires, zouaves and tirailleurs.[15] Towards the end of the war, the 1st Moroccan Division became one of the most decorated units in the French Army.[16] The Foreign Legion suffered high casualties in 1915. It started the year with 21,887 soldiers, NCOs and officers, and ended with 10,683.[17] As a result, the Foreign Legion units fighting on the Western front were put in reserve for reinforcement and reorganization. On November 11, 1915, 3,316 survivors from the 1e and the 2e Etranger were merged into one unit – the Marching Regiment of the Foreign Legion (Régiment de Marche de la Légion étrangère), which in 1920 became the 3rd Foreign Regiment of the French Foreign Legion. Bullard participated in the fighting on the Somme, Champagne, and Verdun, where he was severely wounded on March 5, 1916.

As for the Americans and other volunteers, they were allowed to transfer to the Metropolitan French Army units, including the 170th French Infantry Regiment (Template:Lang-fr). The 170th had a reputation of crack troops, being nicknamed Les Hirondelles de la Mort, or The Swallows of Death.[18] Bullard opted to serve in the 170th Infantry Regiment and the 170 military insignia is displayed on his uniform collar. In the beginning of 1916, the 170th Infantry along with the 48th Infantry Division (Template:Lang-fr), to which the regiment belonged from February 1915 to December 1916, was sent to Verdun. During his convalescence, Bullard was cited for acts of valor at the orders of the regiment on July 3, 1917, and was awarded the croix de guerre.

Aviation

While serving with the 170th Infantry, Bullard was seriously wounded in action in March 1916 at the Battle of Verdun.[13][19] After recovering, he volunteered on October 2, 1916, for the French Air Service (Template:Lang-fr)[20] as an air gunner. He was accepted and underwent training at the Aerial Gunnery School in Cazaux, Gironde.[11] Following this, he went through his initial flight training at Châteauroux and Avord, and received pilot's license number 6950 from the Aéro-Club de France on May 5, 1917.[11][13] Like many other American aviators, Bullard hoped to join the famous squadron Escadrille Americaine N.124, the Lafayette Escadrille, but after enrolling 38 American pilots in the spring and summer of 1916, it stopped accepting applicants. After further training at Avord, Bullard[21] joined 269 American aviators at the Lafayette Flying Corps on November 15, 1916,[22] which were a designation rather than a unit.[23] American volunteers flew with French pilots in different pursuit and bomber/reconnaissance aero squadrons on the Western Front. Edmund L. Gros, who facilitated the incorporation of American pilots in the French Air Service, listed in the October 1917 issue of Flying, an official publication of the Aero Club of America, Bullard's name is on the member roster of the Lafayette Flying Corps.[24]

On June 28, 1917, Bullard was promoted to corporal.[11] On August 27, he was assigned to Escadrille N.93 (Template:Lang-fr), based at Beauzée-sur-Aire south of Verdun, where he stayed until September 13.[25] The squadron was equipped with Nieuport and Spad aircraft that displayed a flying stork as the squadron insignia. Bullard's service record also includes Squadron N.85 (Template:Lang-fr), September 13, 1917 – November 11, 1917, which had a bull insignia.[26][27] He took part in over twenty combat missions, and he is sometimes credited with shooting down one or two German aircraft (sources differ).[14] However, the French authorities could not confirm Bullard's victories.[28]

When the United States entered the war, the United States Army Air Service convened a medical board to recruit Americans serving in the Lafayette Flying Corps for the Air Service of the American Expeditionary Forces. Bullard went through the medical examination, but he was not accepted, as only white pilots were chosen.[10] Some time later, while on a short break from duty in Paris, Bullard allegedly got into an argument with a French commissioned officer and was punished by being transferred to the service battalion of the 170th in January 1918.[14] He served beyond the Armistice, not being discharged until October 24, 1919.[13]

Interwar years

For his World War I service, the French government awarded Bullard the Croix de guerre, Médaille militaire, Croix du combattant volontaire 1914–1918, and Médaille de Verdun, along with several others.[14][19] After his discharge, Bullard returned again to Paris.

Bullard found work as a drummer and a nightclub manager at "Le Grand Duc", and he eventually became the owner of his own nightclub, "L'Escadrille". In 1923, he married Marcelle Straumann, from a wealthy family, but this ended in divorce in 1935, with Bullard gaining custody of their two surviving children, Jacqueline and Lolita.[29] As a popular jazz venue, "Le Grand Duc" gained him many famous friends, including Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, Langston Hughes and French flying ace Charles Nungesser.[10] When World War II began in September 1939, Bullard, who also spoke German, agreed to a request from the French government to spy on the German citizens who still frequented his nightclub.

World War II

Following the German invasion of France in May 1940, Bullard volunteered and served with the 51st Infantry Regiment (Template:Lang-fr) in defending Orléans on June 15, 1940. Bullard was wounded, but he escaped to neutral Spain, and in July 1940 he returned to the United States.

Bullard spent some time in a New York hospital and never fully recovered from his wound. Moreover, he found the fame he enjoyed in France had not followed him to the United States. He worked as a perfume salesman, a security guard, and as an interpreter for Louis Armstrong, but a back injury severely restricted him. In 1945, he attempted to regain his nightclub in Paris, but it had been destroyed during the war. He received a financial settlement from the French government and was able to buy an apartment in Harlem, New York City.

Peekskill riots

In 1949, a concert held by Black entertainer and activist Paul Robeson in Peekskill, New York to benefit the Civil Rights Congress resulted in the Peekskill riots. These were caused in part by members of the local Veterans of Foreign Wars and American Legion chapters, who considered Robeson a communist sympathizer.[30] The concert was scheduled to take place on August 27 at Lakeland Acres, north of Peekskill. Before Robeson arrived, however, a mob attacked the concert-goers with baseball bats and stones. Thirteen people were seriously injured before police put an end to it. The concert was then postponed until September 4.[31] The rescheduled concert took place without incident, but as concert-goers drove away, they passed through long lines of hostile locals, who threw rocks through their windshields.

Bullard was among those attacked after the concert. He was knocked to the ground and beaten by an angry mob, which included members of the state and local law enforcement. The attack was captured on film and can be seen in the 1970s documentary The Tallest Tree in Our Forest and the Oscar-winning documentary narrated by Sidney Poitier, Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist. None of the assailants was ever prosecuted. Graphic pictures of Bullard being beaten by two policemen, a state trooper, and a concert goer were published in Susan Robeson's biography of her grandfather, The Whole World in His Hands: a Pictorial Biography of Paul Robeson.[30]

Later life

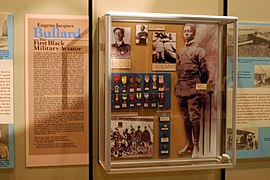

In the 1950s, Bullard was a relative stranger in his own homeland. His daughters had married, and he lived alone in his apartment, which was decorated with pictures of his famous friends and a framed case containing his 15 French war medals. His final job was as an elevator operator at the Rockefeller Center, where his fame as the "Black Swallow of Death" was unknown.

On December 22, 1959, he was interviewed on NBC's Today Show by Dave Garroway and received hundreds of letters from viewers. Bullard wore his elevator operator uniform during the interview.

Bullard died in New York City of stomach cancer on October 12, 1961, at the age of 66.[1] He was buried with military honors in the French War Veterans' section of Flushing Cemetery in the New York City borough of Queens.

Honors

Bullard received 15 decorations from the government of France.[13] In 1954, the French government invited Bullard to Paris to be one of the three men chosen to rekindle the everlasting flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe.[10] In 1959, he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Légion d'honneur[10] by General Charles de Gaulle, who called Bullard a "véritable héros français" ("true French hero"). He also was awarded the Médaille militaire, another high military distinction.[32]

In 1989 he was posthumously inducted into the inaugural class of the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame.[33] On August 23, 1994 — 33 years after his death, and 77 years to the day after the physical that should have allowed him to fly for his own country — Bullard was posthumously commissioned a second lieutenant in the United States Air Force.[10]

1st row :

- Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor)

- Médaille militaire (Military Medal)

2nd row :

- Croix de guerre 1914–1918 avec etoile de bronze (War Cross with bronze star)

- Croix du combattant volontaire 1914–1918 (Volunteer Combatant Cross)

- Croix du combatant (Combatant's Cross)

- Médaille des blessés militaires (Medal for Military Wounded)

3rd row :

- Médaille commémorative de la guerre 1914–1918 (World War I Medal)

- Médaille interalliée 1914–1918, dite de la Victoire (Victory Medal)

- Médaille engagé volontaire (Voluntary Enlistment Medal)

- Médaille commémorative de la bataille de Verdun (Battle of Verdun Medal)

4th row :

- Médaille commémorative de la bataille de la Somme (Battle of the Somme Medal)

- Médaille commémorative de la guerre 1939–1945 (World War II Medal)

- Médaille commémorative des services volontaires de la France libre (Voluntary Service to Free France)

- Médaille des volontaires américains avec l'Armée Française (American Volunteer with French Army Medal)

Note – Bullard was posthumously eligible for the World War I Victory Medal (United States) as he was posthumously commissioned an officer in the United States Army with a date of rank which fell during the eligibility period of the medal.

In print and film

In 1972, Bullard's exploits as a pilot were retold in a biography, The Black Swallow of Death.[34] He is also the subject of the nonfiction young adult memoir Eugene Bullard: World's First Black Fighter Pilot by Larry Greenly.[35]

The 2006 movie Flyboys loosely portrayed Bullard and his comrades in World War I.

In 2012–2014, the French writer Claude Ribbe wrote a book on Bullard[36] and made a television documentary.[37]

Gallery

-

Bullard in his Legionnaire uniform, between 1914 and 1917

-

Bullard in 1917 beside a Nieuport while with Escadrille 93

-

Bullard in January 1918

-

Bullard beside a Caudron trainer

-

Bullard in a group photo

-

Bullard in a group photo

-

Bullard exhibit at the National Museum of the United States Air Force

-

Bullard's awards

-

Bullard's decorations

See also

References

- ^ a b "Eugene Bullard, Ex-Pilot, Dead. American Flew for French in '18". New York Times. October 14, 1961. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

Eugene Jacques Bullard of 10 East 116th Street, a Negro flier who was honored in France for ...

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Harris, Henry Scott (2012). All Blood Runs Red: Life and Legends of Eugene Jacques Bullard: First Black American Military Aviator. NOOK Book (eBook): eBookIt.com. ISBN 9781456612993.

- ^ William I. Chivalette. "Corporal Eugene Jacques Bullard First Black American Fighter pilot". Air & Space Power Journal. www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Dickon, Chris, ed. (2014). "Americans at War in Foreign Forces: A History, 1914–1945". p. 26. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ Buckley, Gail Lumet (2002). "American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution To Desert Storm". p. 169. ISBN 0375760091. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Sutherland, Jonathan (2004). "African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1". p. 119. ISBN 1576077462. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Bielakowski, Alexander M., ed. (2013). "Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1". p. 110. ISBN 9781598844276. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Martin, James B., ed. (2014). "African American War Heroes". p. 33. ISBN 9781610693660. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Craig Lloyd, Columbus State University (November 19, 2002). "Eugene Bullard (1895–1961)". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dominick Pisano (October 12, 2010). "Eugene J. Bullard". National Air and Space Museum.

- ^ a b c d "Bullard James Eugene". www.memoiredeshommes.sga.defense.gouv.fr. Secrétariat Général pour l'Administration – Ministère de la Défense: Mémoire des hommes. pp. 1–2. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Porch, Douglas. The French Foreign Legion: a complete history of the legendary fighting force. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Carnes, Mark C. American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 53–55.

- ^ a b c d Sutherland, Jonathan. African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2004, Vol. 1, p. 86–87.

- ^ Dean, William (2010). "Morale Among French Colonial Troops On The Western Front During World War I: 1914–1918". Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies. 38 (2): 44–61. doi:10.5787/38-2-89.

- ^ Dean, William T. (2011). "Strategic Dilemmas of Colonization: France and Morocco during the Great War". Historian. 73 (4): 730–746. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2011.00304.x.

- ^ Porch, Douglas. The French Foreign Legion: a complete history of the legendary fighting force. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2010, p. 380.

- ^ "Ferdinand Capdevielle". American Volunteers in the French Foreign Legion, 1914–1917. www.scuttlebuttsmallchow.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Venzon, Anne Cipriano. The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Pub, 1995, p. 110.

- ^ "French Air Service". www.theaerodrome.com. The Aerodrome: Aces and Aircraft of World War I. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Hall, James Norman, Charles Nordhoff, and Edgar G. Hamilton. The Lafayette Flying Corps. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920, Volume II, p. 324.

- ^ Gordon, Dennis. The Lafayette Flying Corps: The American Volunteers in the French Air Service in World War One. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Pub, 2000, pp. 78-79.

- ^ "Member Roster Volunteer American Pilots: The Lafayette Flying Corps". New England Air Museum. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Dr. Edmund L. Gros (October 1917). "The members of Lafayette Flying Corps". Flying. 6 (9): 776.

- ^ Sloan, James J. Wings of Honor, American Airmen in World War I: A Compilation of All United States Pilots, Observers, Gunners and Mechanics Who Flew against the Enemy in the War of 1914–1918. Atglen, Pa: Schiffer Military/Aviation History Pub, 1994, p. 64.

- ^ Hall, James Norman, Charles Nordhoff, and Edgar G. Hamilton. The Lafayette Flying Corps. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920, Volume II, p. 330.

- ^ "L'escadrille_85". albindenis.free.fr. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Bailey, Frank W., and Christophe Cony. French Air Service War Chronology, 1914–1918: Day-to-Day Claims and Losses by French Fighter, Bomber and Two-Seat Pilots on the Western Front. London: Grub Street, 2001.

- ^ "Eugene Bullard". American Aviators of WWI. www.usaww1.com. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Robeson, Susan. The Whole World in His Hands: A Pictorial Biography of Paul Robeson. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1981. Chapter 5, The Politics of Persecution, p. 181–183.

- ^ Ford, Carin T. Paul Robeson: "I Want to Make Freedom Ring". Berkeley Heights, New Jersey: Enslow, 2008. Chapter 9, pp. 97–98.

- ^ "Musée National de la Légion d'Honneur: How to research a decorated individual". www.musee-legiondhonneur.fr. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "2nd Lieutenant Eugene Jacques Bullard". Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Carisella, P. J., and James W. Ryan. The Black Swallow of Death: The Incredible Story of Eugene Jacques Bullard, the World's First Black Combat Aviator. Boston: Marlborough House; distributed by Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 1972.

- ^ Greenly, Larry (2013). Eugene Bullard: World's First Black Fighter Pilot. Montgomery: NewSouth Books. ISBN 978-1-58838-280-1.

- ^ RIBBE, Claude (7 June 2012). "Eugène Bullard". Cherche Midi. Retrieved 6 January 2018 – via Amazon.

- ^ "Eugene Bullard (TV Documentary) - ORTHEAL". www.ortheal.com. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

Further reading

- Carisella, P. J., and James W. Ryan. The Black Swallow of Death: The Incredible Story of Eugene Jacques Bullard, the World's First Black Combat Aviator. Boston: Marlborough House; distributed by Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 1972.

- Cockfield, Jamie. All Blood Runs Red . American Heritage, Vol. 46, No. 1, February–March 1995.

- Greenly, Larry W. Eugene Bullard: World's First Black Fighter Pilot. Montgomery, Alabama: NewSouth Books, 2013. ISBN 978-1-58838-280-1

- Gordon, Dennis. The Lafayette Flying Corps: The American Volunteers in the French Air Service in World War One. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military/Aviation History Pub, 2000. ISBN 9780764311086

- Harris, Henry Scott. All Blood Runs Red: Life and Legends of Eugene Jacques Bullard: First Black American Military Aviator. NOOK Book (eBook): eBookIt, 2012. ISBN 9781456612993

- Jouineau, André. Officers and Soldiers of the French Army 1918: 1915 to Victory. Paris: Histoire & Collections, 2008.

- Lloyd, Craig. Eugene Bullard: Black Expatriate in Jazz Age Paris. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8203-2192-3

- Mason, Herbert Molloy Jr. High Flew the Falcons: The French Aces of World War I. New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1965.

- Ribbe, Claude Eugène Bullard: récit. Paris, Le Cherche Midi, 2012.

- Sloan, James J. Wings of Honor, American Airmen in World War I: A Compilation of All United States Pilots, Observers, Gunners and Mechanics Who Flew against the Enemy in the War of 1914–1918. Atglen, Pa: Schiffer Military/Aviation History Pub, 1994.

External links

- James Eugene Bullard Base des Personnels de l'aéronautique militaire, Secrétariat Général pour l'Administration, Ministère de la Defence, France

- Eugene Bullard (1895-1961) New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Eugene J. Bullard Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

- Eugene Jacques Bullard U.S. Air Force Museum

- Eugene Jacques Bullard American Volunteers in the French Foreign Legion, 1914–1917

- Eugene Bullard at Find a Grave

- 'The First Black Fighter Pilot', by Jack Doyle, Jan. 23, 2016

- 1895 births

- 1961 deaths

- Deaths from stomach cancer

- Deaths from cancer in New York (state)

- People from Columbus, Georgia

- African-American military personnel

- African-American boxers

- American people of Haitian descent

- American people of Native American descent

- French people of African-American descent

- French people of Haitian descent

- French military personnel of World War I

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France)

- Lafayette Escadrille

- Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion

- Burials at Flushing Cemetery

- American male boxers

- Boxers from Georgia (U.S. state)