Exothermic reaction

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2013) |

An exothermic reaction is a chemical reaction that releases energy by light or heat. It is the opposite of an endothermic reaction.[1]

Expressed in a chemical equation: reactants → products + energy

Overview

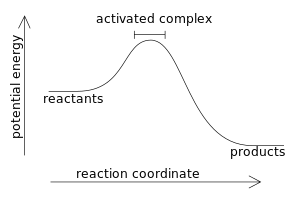

An exothermic reaction is a chemical or physical reaction that releases heat. It gives net energy to its surroundings. That is, the energy needed to initiate the reaction is less than the energy released.[2]

When the medium in which the reaction is taking place gains heat, the reaction is exothermic. When using a calorimeter, the total amount of heat that flows into (or through) the calorimeter is the negative of the net change in energy of the system.

The absolute amount of energy in a chemical system is difficult to measure or calculate. The enthalpy change, ΔH, of a chemical reaction is much easier to work with. The enthalpy change equals the change in internal energy of the system plus the work needed to change the volume of the system against constant ambient pressure. A bomb calorimeter is very suitable for measuring the energy change, ΔH, of a combustion reaction. Measured and calculated ΔH values are related to bond energies by:

- ΔH = energy used in forming product bonds − energy released in breaking reactant bonds

In an exothermic reaction, by definition, the enthalpy change has a negative value:

- ΔH < 0

since a larger value (the energy released in the reaction) is subtracted from a smaller value (the energy used for the reaction). For example, when hydrogen burns:

- 2H2 (g) + O2 (g) → 2H2O (g)

- ΔH = −483.6 kJ/mol of O2 [3]

The most commonly available hand warmers make use of the oxidation of iron to achieve an exothermic reaction:

- 4Fe(s) + 3O2(g) → 2Fe2O3(s).

Examples of exothermic reactions

- Combustion reactions of fuels

- Neutralization

- Burning of a substance

- Deposition of dry ice (carbon dioxide) from the gaseous state

- Adding water to anhydrous copper(II) sulfate

- The thermite reaction

- Reactions taking place in a self-heating can based on lime aluminium

- Many corrosion reactions such as oxidation of metals

- Most polymerization reactions

- The Haber process of ammonia production

- Respiration

- Decomposition of vegetable matter into compost

- Solution of sulfuric acid into water

- Dehydration of sugars upon contact with sulfuric acid

- Detonation of nitroglycerin

- Nuclear fission of uranium-235

Other points to think about

- The concept and its opposite number endothermic relate to the enthalpy change in any process, not just chemical reactions.

- In endergonic reactions and exergonic reactions it is the sign of the Gibbs free energy that determines the equilibrium point, and not enthalpy. The related concepts endergonic and exergonic apply to all physical processes.

- The conceptually related endotherm and ectotherm (or sometimes exotherm) are concepts in animal physiology.

- In quantum numbers, when any excited energy level goes down to its original level for example: when n=4 fall to n=2, energy is released so, it is exothermic.

- Where an exothermic reaction causes heating of the reaction vessel which is not controlled, the rate of reaction can increase, in turn causing heat to be evolved even more quickly. This positive feedback situation is known as thermal runaway. An explosion can also result from the problem.

Measurement

Heat production or absorption in either a physical process or chemical reaction is measured using calorimetry. One common laboratory instrument is the reaction calorimeter, where the heat flow into or from the reaction vessel is monitored. The technique can be used to follow chemical reactions as well as physical processes such as crystallization and dissolution.

Energy released is measured in Joule per mole. The reaction has a negative ΔH(heat change) value due to heat loss. e.g.: -123 J/mol

See also

- Chemical thermodynamics

- Differential scanning calorimetry

- Endergonic

- Exergonic

- Endergonic reaction

- Exergonic reaction

- Exothermic

- Endothermic reaction

- Endotherm

References

- ^ Article written by Anne Marie Helmenstine, Ph.D on exothermic and endothermic reactions http://chemistry.about.com/cs/generalchemistry/a/aa051903a.htm

- ^ "Endothermic and Exothermic Reactions". About Chemistry. 3 February 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ http://chemistry.osu.edu/~woodward/ch121/ch5_enthalpy.htm