Falling Autumn Leaves

| Falling Autumn Leaves (F486) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1888 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 73 cm × 92 cm (29 in × 36 in) |

| Location | Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo |

| Falling Autumn Leaves (F487) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1888 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 72 cm × 91 cm (28 in × 36 in) |

| Location | Private collection |

Fall of Leaves (original French title: Chûte de feuillus), or Falling Autumn Leaves is a pair of paintings (in French pendants, i. e. counterparts) by the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh. They were executed during the two months at the end of 1888 that his artist friend Paul Gauguin spent with him at The Yellow House in Arles, France.

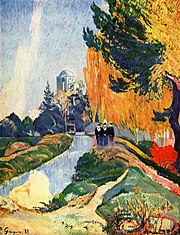

Les Alyscamps

Following months of correspondence, Paul Gauguin joined van Gogh in Arles in October 1888. Both were intent on depicting a "non-naturalist landscape". The paintings are among the first works that the pair painted following Gauguin's arrival.[1]

Van Gogh and Gauguin visited an ancient Roman necropolis, Les Alyscamps, which had been built outside the city walls. Over time the grounds were overtaken by factories and the railroad. The city relocated some of the sarcophagi in a long alley lined with benches and poplar trees that led to a Romanesque chapel which became known as the Allée des Tombeaux. It quickly became a lover's lane celebrated throughout France.[2][3]

The paintings

During a period of bad weather van Gogh worked on a second pair of "Les Alyscamps" paintings, which were taken from a vantage point above the lane and looking through the poplar trees, made in the studio. The yellow-orange of the leaves contrast with the violet-blue trunks of the poplar trees. This painting, made shortly after Gauguin's arrival in Arles, was unique in van Gogh's body of work and representative of the artistic achievements realised by two great artists working together. To Émile Bernard van Gogh described the collaborative process as a pooling of thoughts and techniques where each artist creates their own unique work that is different, yet complements one another. Van Gogh believed that his pair of paintings Falling Autumn Leaves was just such a collaborative effort influenced by his own ideas as well as those of Gauguin and Bernard.[4]

The paintings were made on Gauguin's jute which with Van Gogh’s brushstroke made a finished tapestry-like texture. The high vantage point represented in the work resembled that of Gauguin's Vision After the Sermon. Creating a composition of a landscape viewed through the trunks of trees was something used previously by Bernard. Van Gogh used complementary, contrasting colors to intensify the effect of each color. The blue poplar trunks against the yellow path of leaves. Green used against red. Violet was paired with apricot. To his sister, Vincent wrote of selection and placement of colors "which cause each other to shine brilliantly, which form a couple, which complete each other like man and woman."[5]

Van Gog's imagination created the figures in the paintings. In one, a couple of a thin man with an umbrella is paired with a large woman, much like van Gogh's image of a woman he might settle down with. On the lane is also a red-dressed woman. The other painting holds a couple who walk along the lane between stone sarcophagi, a yellow sunset at their backs.[5]

Van Gogh's other Les Alyscamps paintings

Van Gogh made another pair of paintings at Les Alyscamps.

-

Les Alyscamps

1888

Private collection (F569) -

Les Alyscamps

1888

Collection Basil P. and Elise Goulandris, Laussane, Switzerland

Gauguin's paintings

For his painting of Les Alyscamps, painted on the same day as van Gogh's, Gauguin chose a different vantage point, and excluded any reference to ancient sarcophagi.[1]

References

Bibliography

- Gayford, M (2006). The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles. Penguin. ISBN 0-670-91497-5.

- Naifeh, Steven; Smith, Gregory White. Van Gogh: The Life. Profile Books, 2011. ISBN 978-1846680106

External links

Media related to Falling Autumn Leaves (F486) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Falling Autumn Leaves (F486) at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Falling Autumn Leaves (F487) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Falling Autumn Leaves (F487) at Wikimedia Commons