Fatimid art

Fatimid art refers to Islamic artifacts and architecture from the Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171), principally in Egypt and North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate was initially established in the Mahgreb, with its roots in a ninth-century Shia Ismailist religious movement originating in Iraq and Iran. Many monuments survive in the Fatimid cities founded in North Africa, starting with Mahdia, on the Tunisian coast, the principal city prior to the conquest of Egypt in 969 and the building of al-Qahira, the "City Victorious", now part of modern day Cairo. The period was marked by a prosperity amongst the upper echelons, manifested in the creation of opulent and finely wrought objects in the decorative arts, including carved rock crystal, lustreware and other ceramics, wood and ivory carving, gold jewelry and other metalware, textiles, books and coinage. These items not only reflected personal wealth, but were used as gifts to curry favour abroad. The most precious and valuable objects were amassed in the caliphal palaces in al-Qahira. In the 1060s, following several years of drought during which the armies received no payment, the palaces were systematically looted, the libraries largely destroyed, precious gold objects melted down, with a few of the treasures dispersed across the medieval Christian world. Afterwards Fatimid artifacts continued to be made in the same style, but were adapted to a larger populace using less precious materials.

In 1067-68 the great treasury of the Fatimids was ransacked when the troops rebelled and demanded to be paid. The stories of this plundering mention not only great quantities of pearls and jewels, crowns, swords, and other imperial accoutrements but also many objects in rare materials and of enormous size. Eighteen thousand pieces of rock crystal and cut glass were swiftly looted from the palace, and twice as many jewelled objects; also large numbers of gold and silver knives all richly set with jewels; valuable chess and backgammon pieces; various types of hand mirrors, skilfully decorated; six thousand perfume bottles in gilded silver; and so on. More specifically, we learn of enormous pieces of rock crystal inscribed with caliphal names; of gold animals encrusted with jewels and enamels; of a large golden palm tree; and even of a whole garden partially gilded and decorated with niello. There was also an immensely rich treasury of furniture, carpets, curtains, and wall coverings, many embroidered in gold, often with designs incorporating birds and quadrupeds, kings and their notables, and even a whole range of geographical vistas.Relatively few of these objects have survived, most of them very small; but the finest are impressive enough to lend substance to the vivid picture painted in the historical accounts of this vanished world of luxury.

Rock crystal ewers

Rock crystal ewers are pitchers carved from a single block of rock crystal. They were made by Islamic Fatimid artisans and are considered to be amongst the rarest objects in Islamic art.[1] There are a few that survived and are now in collections across Europe. They are often in cathedral treasuries, where they were rededicated after being captured from their original Islamic settings. Made in Egypt in the late 10th century, the ewer pictured is exquisitely decorated with fantastic birds, beasts and twisting tendrils. The Treasure of Caliph Mostansir-Billah at Cairo, which was destroyed in 1062, apparently contained 1800 rock crystal vessels.

Great skill was required to hollow out the raw rock crystal without breaking it and to carve the delicate, often very shallow, decoration.

Fatimid architecture

In architecture, the Fatimids followed Tulunid techniques and used similar materials, but also developed those of their own. In Cairo, their first congregational mosque was al-Azhar mosque ("the splendid") founded along with the city (969–973), which, together with its adjacent institution of higher learning (al-Azhar University), became the spiritual center for Ismaili Shia. The Mosque of al-Hakim (r. 996–1013), an important example of Fatimid architecture and architectural decoration, played a critical role in Fatimid ceremonial and procession, which emphasized the religious and political role of the Fatimid caliph. Besides elaborate funerary monuments, other surviving Fatimid structures include the Aqmar Mosque (1125)[2] as well as the monumental gates for Cairo's city walls commissioned by the powerful Fatimid emir and vizier Badr al-Jamali (r. 1073–1094).

Gallery

-

Rock crystal ewer, Victoria and Albert Museum

-

11th century gold armlet from Syria. Freer Gallery of Art

-

Lustre ware cup with eagle. Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Ceramic bowl, Bardo National Museum

-

Carved stone column in the al-Aqmar Mosque in Cairo

-

Mashad al-Sayyida Ruqayya in Cairo

-

Carved and engraved ivory panel with hunters, Louvre

-

12th century linen tapestry with silk embroidery, Royal Ontario Museum

-

Page from the Blue Qur'an, Gold and silver leaf on indigo-dyed parchment, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

10th century gold dinar, Caliphate of al-Muizz Lideenillah, British Museum

-

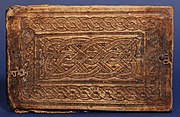

10th century leather bookbinding, Kairouan

-

10th-11th century illustration of rooster, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

11th-12th century illustration of hare from lost bestiary, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

11th-12th century illustration of lion from lost bestiary, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

12th-13th century copy of 11th century world map from "Book of Curiosities", Bodleian Library

Notes

- ^ Fatimid Rock Crystal Ewers, Most Valuable Objects in Islamic Art

- ^ Doris Behrens-Abouseif (1992), Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction, BRILL, p. 72

- ^ This ewer, inscribed with the name of Husain ibn Jawhar,a general of the Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, was accidentally dropped by an assistant in the museum in 1998 and shattered beyond repair.

References

History of art

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2007), Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic art and architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-13542-4

- Jackson, Anna (ed.) (2001). V&A: A Hundred Highlights. V&A Publications.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Ellis, Marianne (2001), Embroideries and samplers from Islamic Egypt, Ashmolean Museum, ISBN 1-85444-135-3

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009), The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture, Volumes 1–3, Oxford University Press

- Barrucand, Marianne, ed. (1999), L'Égypte fatimide: son art et son histoire : actes du colloque organisé à Paris les 28, 29 et 30 mai 1998, Presses de l'université de Paris-Sorbonne

- Yeomans, Richard (2006), The art and architecture of Islamic Cairo, Garnet, ISBN 1-85964-154-7

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins, Marilyn (2001), Islamic art and architecture 650-1250, Pelican history of art, vol. 51 (2nd ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-08869-8

- Evans, Helen C.; Wixom, William D., eds. (2000), Glory of Byzantium: Arts and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-300-08616-4

- Qaddumī, Ghādah Ḥijjāwī (1996), Book of gifts and rarities, Harvard Middle Eastern monographs, vol. 29, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-932885-13-6t

History

- Hoffman, Eva Rose F., ed. (2007), Late antique and medieval art of the Mediterranean world, Blackwell anthologies in art history, vol. 5, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 1-4051-2072-X

- Brett, Michael (1975), Fage, J. D. (ed.), The Fatimid revolution and its aftermath in North Africa, The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 589–636, ISBN 0-521-21592-7

- Hrbek, Ivan (1977), Oliver, R. (ed.), The Fatimids, The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600, Volume 3, Cambridge University Press, pp. 10–27, ISBN 0-521-21592-7

- Sanders, Paula A. (1994), Ritual, politics, and the city in Fatimid Cairo, SUNY series in medieval Middle East history, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1781-6

- Walker, Paul E. (1998), Daly, M. W.; Petry, Carl F. (eds.), The Ismaili Dawa and the Fatimid caliphate, The Cambridge history of Egypt, vol. I, Cambridge University Press, pp. 120–150, ISBN 0521068851

- Sanders, Paula A. (1998), Daly, M. W.; Petry, Carl F. (eds.), The Fatimid state, 969-1171, The Cambridge history of Egypt, vol. I, Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–174, ISBN 0521068851

- Walker, Paul E. (2002), Exploring an Islamic empire: Fatimid history and its sources, Ismaili heritage series, vol. 7, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-86064-692-1

- Daftary, Farhad (2007), The Ismailıis: their history and doctrines (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-61636-0

- Brett, Michael (2001), The rise of the Fatimids: the world of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the fourth century of the Hijra, tenth century CE, The Medieval Mediterranean, vol. 30, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-11741-5

- Bresc, Henri; Guichard, Pierre (1997), Fossier, Robert (ed.), Explosions within Islam, 850-1200, The Cambridge illustrated history of the Middle Ages, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 146–202, ISBN 0-521-26645-9

- Meri, Josef W. (2005), Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-96690-6

External links

- Fatimid Rock Crystal Ewers, Most Valuable Objects in Islamic Art

- The Masterpiece Minbar, extract from Saudi Aramco World (1998) of an article by Jonathan Bloom

- Trésors fatimides du Caire, exhibition of Fatimid art at the Institut du Monde Arabe

- Bronze animal statuary (aquamaniles, incense burners, fountain fixtures. perfume dispensers): lion 1, lion 2, lion 3, cheetah, stag, hind, gazelle, ram, hare, bird, parrot

- Rock crystal ewers: Venice 1, Venice 2, Berlin

- Carved ivory frame, Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art

![Rock crystal ewer from the treasury of Lorenzo de Medici, Palazzo Pitti[3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/78/Museo-degli-ArgentiFatimid.jpg/126px-Museo-degli-ArgentiFatimid.jpg)