Vachellia xanthophloea

| Fever tree | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Caesalpinioideae |

| Clade: | Mimosoid clade |

| Genus: | Vachellia |

| Species: | V. xanthophloea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vachellia xanthophloea (Benth.) P. J. H. Hurter[2]

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Acacia xanthophloea Benth. | |

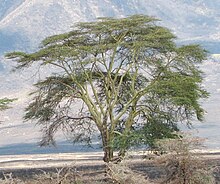

Vachellia xanthophloea is a tree in the family Fabaceae, commonly known in English as the fever tree.[3] This species of Vachellia is native to eastern and southern Africa (Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Somalia, South Africa, Eswatini, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe). It has also become a landscape tree in other warm climates, outside of its natural range.

Description

[edit]The trees grow to a height of 15–25 m (49–82 ft). The characteristic bark is smooth, powdery and greenish yellow, although new twigs are purple, flaking later to reveal the characteristic yellow.[4] It is one of the few trees where photosynthesis takes place in the bark. Straight, white spines grow from the branch nodes in pairs. The leaves are twice compound, with small leaflets (8 mm × 2 mm or 0.3 in × 0.1 in). The flowers are produced in scented pale cream spherical inflorescences, clustered at the nodes and towards the ends of the branches. The pale brown pods contain 5–10 elliptical, flattened green seeds and are 5–19 cm (2.0–7.5 in) long, straight, flat and rather papery, the segments are mostly longer than they are wide, often breaking up to form small clusters of segments each containing an individual seed. As the pods mature they change colour from green to pale greyish brown.[4]

Fever trees are fast growing and short lived. They have a tendency to occur as single-aged stands, and are subject to stand-level diebacks that have been variously attributed to elephants, water tables, and synchronous senescence.[5][6][7][8]

Etymology

[edit]

The name xanthophloea is derived from Greek and means "yellow bark" (ξανθός "yellow, golden"; φλοιός "bark"). The common name, fever tree, comes from its tendency to grow in swampy areas: early European settlers in the region noted that malarial fever was contracted in areas with these trees. It is now understood that malarial fever is spread by mosquitos living in the swampy areas that often support this tree species, and not by the tree species itself. This is because mosquitos often lay eggs in moist swampy areas, which they need blood to do.[9]

Ecology

[edit]

Vachellia xanthophloea is found growing near swamps, riverine forests or on lake shores, in semi-evergreen bush land and woodland where there is a high groundwater table. In seasonally flooded areas it often forms dense single species stands.[4]

The leaves and pods are used to provide food for livestock while the young branches and foliage are eaten by African elephants while giraffe and vervet monkeys eat the pods and leaves. The flowers are used for foraging by bees and provides favoured nesting sites for birds. Like other acacias and Fabaceae it is a nitrogen fixer, so improves soil fertility.[4] The gum is part of the diet of the Senegal bushbaby (Galago senegalensis) especially in the dry season.[10]

Butterflies recorded as feeding on Vachellia xanthophloea in Kenya included the Kikuyu ciliate blue (Anthene kikuyu), Pitman's hairtail (Anthene pitmani), common ciliate blue (Anthene definita), African babul blue (Azanus jesous), Victoria's bar (Cigaritis victoriae) and common zebra blue (Leptotes pirithous). In addition 30 species of larger moths have been recorded as feeding on this tree.[11]

Other uses

[edit]

Vachellia xanthophloea are planted next to dams and streams on farms to control soil erosion, as a live fence or hedge and in ornamental planting for shade and shelter in amenity areas. Vachellia xanthophloea is often planted as a source of firewood, but its gummy sap leaves a thick, black, tarlike residue when burnt. The valuable timber of Vachellia xanthophloea is pale reddish brown with a hard, heavy texture, and, because it is liable to crack, it should be seasoned before use. The timber is used to make poles and posts.[4]

Invasive species

[edit]

In Australia, Vachellia xanthophlea is a prohibited invasive plant in the state of Queensland under the Biosecurity Act 2014, under which it must not be given away, sold, or released into the environment without a permit. The act further requires that all sightings of Vachellia xanthophlea are to be reported to the appropriate authorities within 24 hours and that within Queensland everyone is obliged to take all reasonable and practical steps to minimise the risk of Vachellia xanthophlea spreading until they have received advice from an authorised officer. Thus far it has only been found in a few gardens and not in the "wild".[12] It is also a "declared pest" in Western Australia.[13]

In popular culture

[edit]These trees are immortalized by Rudyard Kipling in one of his Just So Stories, "The Elephant's Child", wherein he repeatedly refers to "the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees".[14]

Shamanic usage

[edit]This tree has been used for thousands of years by African tribes as a divination tool. Bark from this tree and four other herbs including Silene capensis (African dream root) and Synaptolepis kirkii are boiled into a brew. This is taken to induce lucid dreams, which they call "white paths". Before going to sleep a question is asked that will be answered in their dreams. Medicinally, the roots and a powder made from bark stripped from the trunk are used as an emetic and as a prophylactic against malaria.[4]

Gallery

[edit]-

A fever tree planted outside of its natural range at Ilanda Wilds

-

Planted at Umdoni Bird Sanctuary

-

Foliage and branches

-

Leaves

-

Branches

-

A spider on the stem

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI).; IUCN SSC Global Tree Specialist Group (2019). "Vachellia xanthophloea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T147140093A147140095. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T147140093A147140095.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Kyalangalilwa B, Boatwright JS, Daru BH, Maurin O, van der Bank M (2013). "Phylogenetic position and revised classification of Acacia s.l. (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae) in Africa, including new combinations in Vachellia and Senegalia". Bot J Linn Soc. 172 (4): 500–523. doi:10.1111/boj.12047. hdl:10566/3454.

- ^ "Vachellia xanthophloea". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Acacia xanthophloea". WorldAgroforestryCenter 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Western, D. & C. Van Praet (1973). "Cyclical changes in the habitat and climate of an East African ecosystem". Nature. 241 (5385): 104–106. Bibcode:1973Natur.241..104W. doi:10.1038/241104a0. S2CID 4206005.

- ^ Young, T. P. & W. K. Lindsay (1988). "Role of even-aged population structure in the disappearance of Acacia xanthophloea woodlands". African Journal of Ecology. 26: 69–72. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1988.tb01130.x.

- ^ Ruess, R. W. & F. L. Walter (1990). "The impact of large herbivores on the Seronera woodlands, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania". African Journal of Ecology. 28 (4): 259–275. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1990.tb01161.x.

- ^ Mills, A. J. (2006). "The role of salinity and sodicity in the dieback of Acacia xanthophloea in Ngorongoro Caldera, Tanzania". African Journal of Ecology. 44: 61–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00616.x.

- ^ Vachellia xanthophloea (as Acacia xanthophloea) entry at PlantZAfrica.com

- ^ Kingdon, Jonathan; Happold, David; Hoffmann, Mike; Happold, Meredith; Kalina, Jan (2013). Mammals of Africa: Volumes I-6. A & C Black. ISBN 978-1408122570.

- ^ Agassiz, David J. L.; Harper, David M. (2009). "The Macrolepidoptera Fauna of Acacia in the Kenyan Rift Valley (Part 1)" (PDF). Trop. Lepid. Res. 19 (1): 4–8.

- ^ "Yellow fever tree". The State of Queensland. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ "Acacia: declared pest". Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ "The Elephant's Child".

Bibliography

[edit]- Pooley, E. (1993). The Complete Field Guide to Trees of Natal, Zululand and Transkei. ISBN 0-620-17697-0.

External links

[edit]- Dressler, S.; Schmidt, M. & Zizka, G. (2014). "Acacia xanthophloea". African plants – a Photo Guide. Frankfurt/Main: Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg.