Garter snake: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 216.235.174.121 (talk) to last version by 96.233.115.20 |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

There is little variation within the pattern of scales among the different varieties of garter snakes, but coloration varies widely across varieties and geographic regions. |

There is little variation within the pattern of scales among the different varieties of garter snakes, but coloration varies widely across varieties and geographic regions. |

||

The pattern on |

The pattern on tsshese snakes consists of one, two or three longitudinal stripes on the back, typically red, yellow, blue, orange or white. The snake genus earned its common name because people described the stripes as resembling a [[Garter (stockings)|garter]]. In between the stripes on the pattern are rows with blotchy spots. Even within a single species the color in the stripes and spots and background can differ from a dark red to a lime green. In some species the stripes vary little in color from the adjacent bands or background and are not readily seen. Most garter snakes are under 60 cm (24 inches) long, but can be larger. ''T. gigas'' is capable of attaining lengths of 160 cm. The average lifespan is 6 years. |

||

== Diet == |

== Diet == |

||

Revision as of 01:29, 6 August 2009

| Garter snake | |

|---|---|

| |

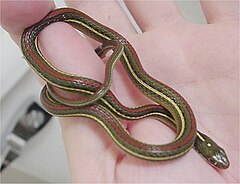

| Coast garter snake Thamnophis elegans terrestris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Thamnophis Fitzinger, 1843

|

| Species | |

|

See Taxonomy section. | |

A garter snake is any species of North American snake within the genus Thamnophis. Because of the similarity in the sound of the words, combined with where people often see them, they are sometimes called garden snakes, gardner snakes or gardener snakes, or even garder snakes or guarder snakes. They are harmless to humans. Garter snakes are common across North America, from Canada to Central America, and they are the single most widely distributed genus of reptile in North America. In fact, the common garter snake, T. sirtalis, is the only species of snake to be found in Alaska, and is one of the northernmost species of snake in the world, possibly second only to the Crossed Viper, Vipera berus. The genus is so far ranging due to its unparticular diet and adaptability to different biomes and landforms, from marshes to hillsides to drainage ditches and even vacant lots, in both dry and wet regions, with varying proximity to water and rivers. However, in the western part of North America, these snakes are more water loving than in the eastern portion. Northern populations hibernate in larger groups than southern ones. Despite the decline in their population from collection as pets (especially in the more northerly regions in which large groups are collected at hibernation), pollution of aquatic areas, and introduction of bullfrogs and bass as predators, this is still a very commonly found snake. The San Francisco garter snake, Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia, however, is an endangered subspecies and has been on the endangered list since 1967 and has a red and orange colored pattern on its back. Predation by crayfish has also been responsible for the decline of the narrow head garter snake, T. rufipunctatus.

There is no real consensus on the classificiation of species Thamnophis and disagreement among taxonomists and sources, such as field guides, over whether two types of snakes are separate species or subspecies of the same species is common. They are also closely related to the snakes of the genus Nerodia, and some species have been moved back and forth between genera.

Description

There is little variation within the pattern of scales among the different varieties of garter snakes, but coloration varies widely across varieties and geographic regions.

The pattern on tsshese snakes consists of one, two or three longitudinal stripes on the back, typically red, yellow, blue, orange or white. The snake genus earned its common name because people described the stripes as resembling a garter. In between the stripes on the pattern are rows with blotchy spots. Even within a single species the color in the stripes and spots and background can differ from a dark red to a lime green. In some species the stripes vary little in color from the adjacent bands or background and are not readily seen. Most garter snakes are under 60 cm (24 inches) long, but can be larger. T. gigas is capable of attaining lengths of 160 cm. The average lifespan is 6 years.

Diet

Garter snakes, like all snakes, are carnivorous. Their diet consists of almost any creature that they are capable of overpowering: slugs, earthworms, insects, leeches, lizards, spiders, amphibians, birds, fish, toads and rodents. When living near the water, they will eat other aquatic animals. The ribbon snake in particular favors frogs (including tadpoles), readily eating them despite their strong chemical defenses. Food is swallowed whole. Garter snakes often adapt to eat whatever they can find. Although they dine mostly upon live animals, they will sometimes eat eggs.

Behavior

Garter snakes of all species are gregarious (when not in brumation or aestivation). They have complex systems of pheromonal communication. They can locate other snakes by following their pheromone-scented trails. Male and female skin pheromones are so different as to be immediately distinguishable. However, sometimes male garter snakes produce both male and female pheromones. During mating season, this fact fools other males into attempting to mate with these "she-males". She-males have been shown to garner more copulations than normal males in the mating balls that form at the den when females emerge into the mating melee.

If disturbed, a garter snake may coil and strike, but typically it will hide its head and flail its tail. These snakes will also discharge a malodorous, musky-scented secretion from a gland near the anus. They often use these techniques to escape when ensnared by a predator. They will also slither into the water to escape a predator on land. Hawks, crows, raccoons, crayfish and other snake species (such as the coral snake and king snake) will eat garter snakes, with even shrews and frogs eating the juveniles.

Being heterothermic, like all reptiles, garter snakes bask in the sun to regulate their body temperature. During hibernation, garter snakes typically occupy large, communal sites called hibernacula. These snakes will migrate large distances to brumate. Most Garter snakes hide or live in dark places but often come out of their homes to bask in the sun.

Reproduction

Garter snakes go into brumation before they mate. They stop eating for about two weeks beforehand to clear their stomach of any food that would rot there otherwise. Garter snakes begin mating as soon as they emerge from brumation. During mating season, the males mate with several females. In chillier parts of their range, male common garter snakes awaken from brumation first, giving themselves enough time to prepare to mate with females when they finally appear. Males come out of their dens and, as soon as the females begin coming out, surround them. Female garter snakes produce a sex-specific pheromone that attracts male snakes in droves, sometimes leading to intense male-male competition and the formation of mating balls of up to 100 males per female. After copulation, a female leaves the den/mating area to find food and a place to give birth. Female garter snakes are able to store the male's sperm for years before fertilization. The young are incubated in the lower abdomen, at about the midpoint of the length of the mother's body. Garter snakes are ovoviviparous, meaning they give birth to live young. Gestation is two to three months in most species. As few as 3 or as many as 80 snakes are born in a single litter. The babies are independent upon birth.

Venom

Garters were long thought to be nonvenomous, but recent discoveries have revealed that they do in fact produce a mild neurotoxic venom.[1] Garter snakes are nevertheless harmless to humans due to the very low amounts of venom they produce, which is comparatively mild, and the fact that they lack an effective means of delivering it. They do have enlarged teeth in the back of their mouth, but unlike many rear-fanged colubrid snakes, garter snakes do not have a groove running down the length of the teeth that would allow it to inject venom into its prey. The venom is delivered via a Duvernoy's gland, secreted between their lips and gums.[2][3] Whereas most venomous snakes have anterior or forward venom glands, the Duvernoy's gland of garters are posterior (to the rear) of the snake's eyes.[4] The mild poison is spread into wounds through a chewing action. The properties of the venom are not well known, but it appears to contain 3FTx, commonly known as three-finger toxin, which is a neurotoxin commonly found in the venom of colubrids and elapids. A bite may result in mild swelling and an itching sensation. There are no known cases of serious injury and extremely few with symptoms of envenomation.

Taxonomy

- Longnose Garter Snake, Thamnophis angustirostris (Kennicott, 1860)

- Aquatic Garter Snake, Thamnophis atratus

- Santa Cruz Garter Snake, Thamnophis atratus atratus (Kennicott, 1860)

- Oregon Garter Snake, Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus (Fitch, 1936)

- Diablo Range Garter Snake, Thamnophis atratus zaxanthus (Boundy, 1999)

- Shorthead Garter Snake, Thamnophis brachystoma (Cope, 1892)

- Butler's Garter Snake, Thamnophis butleri (Cope, 1889)

- Goldenhead Garter Snake, Thamnophis chrysocephalus (Cope, 1885)

- Western Aquatic Garter Snake, Thamnophis couchii (Kennicott, 1859)

- Blackneck Garter Snake, Thamnophis cyrtopsis

- Western Blackneck Garter Snake, Thamnophis cyrtopsis cyrtopsis (Kennicott, 1860)

- Eastern Blackneck Garter Snake, Thamnophis cyrtopsis ocellatus (Cope, 1880)

- Tropical Blackneck Garter Snake, Thamnophis cyrtopsis collaris (Jan, 1863)

- Tepalcatepec Valley Garter Snake, Thamnophis cyrtopsis postremus (Smith, 1942)

- Yellow-throated Garter Snake, Thamnophis cyrtopsis pulchrilatus (Cope, 1885)

- Western Terrestrial Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans

- Arizona Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans arizonae (Tanner & Lowe, 1989)

- Mountain Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans elegans (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Mexican Wandering Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans errans (Smith, 1942)

- Coast Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans terrestris (Fox, 1951)

- Wandering Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans vagrans (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Upper Basin Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans vascotanneri (Tanner & Lowe, 1989)

- Sierra San Pedro Mártir Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans hueyi (Van Denburgh & Slevin, 1923)

- Thamnophis eques

- Mexican Garter Snake, Thamnophis eques eques (Reuss, 1834)

- Laguna Totolcingo Garter Snake, Thamnophis eques carmenensis (Conant, 2003)

- Thamnophis eques cuitzeoensis (Conant, 2003)

- Thamnophis eques diluvialis (Conant, 2003)

- Thamnophis eques insperatus (Conant, 2003)

- Northern Mexican Garter Snake, Thamnophis eques megalops (Kennicott, 1860)

- Thamnophis eques obscurus (Conant, 2003)

- Thamnophis eques patzcuaroensis (Conant, 2003)

- Thamnophis eques scotti (Conant, 2003)

- Thamnophis eques virgatenuis (Conant, 1963)

- Montane Garter Snake, Thamnophis exsul (Rossman, 1969)

- Highland Garter Snake, Thamnophis fulvus (Bocourt, 1893)

- Giant Garter Snake, Thamnophis gigas (Fitch, 1940)

- Godman's Garter Snake, Thamnophis godmani (Günther, 1894)

- Two-striped Garter Snake, Thamnophis hammondii (Kennicott, 1860)

- Checkered Garter Snake, Thamnophis marcianus (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Blackbelly Garter Snake, Thamnophis melanogaster

- Gray Blackbelly Garter Snake, Thamnophis melanogaster canescens (Smith, 1942)

- Chihuahuan Blackbelly Garter Snake, Thamnophis melanogaster chihuahuanensis (Tanner, 1959)

- Lined Blackbelly Garter Snake, Thamnophis melanogaster linearis (Smith, Nixon & Smith, 1950)

- Mexican Blackbelly Garter Snake, Thamnophis melanogaster melanogaster (Peters, 1864)

- Tamaulipan Montane Garter Snake, Thamnophis mendax (Walker, 1955)

- Northwestern Garter Snake, Thamnophis ordinoides (Baird & Girard, 1852)

- Western Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis proximus

- Chiapas Highland Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis proximus alpinus (Rossman, 1963)

- Arid Land Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis proximus diabolicus (Rossman, 1963)

- Gulf Coast Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis proximus orarius (Rossman, 1963)

- Western Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis proximus proximus (Say, 1823)

- Redstripe Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis proximus rubrilineatus (Rossman, 1963)

- Mexican Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis proximus rutiloris (Cope, 1885)

- Eastern Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis radix (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Rossman's Garter Snake, Thamnophis rossmani (Conant, 2000)

- Narrowhead Garter Snake, Thamnophis rufipunctatus

- Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis sauritus

- Bluestripe Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis sauritus nitae (Rossman, 1963)

- Peninsula Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis sauritus sackenii (Kennicott, 1859)

- Eastern Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis sauritus sauritus (Linnaeus, 1766)

- Northern Ribbon Snake, Thamnophis sauritus septentrionalis (Rossman, 1963)

- Longtail Alpine Garter Snake, Thamnophis scalaris (Cope, 1861)

- Short-tail Alpine Garter Snake, Thamnophis scaliger (Jan, 1863)

- Common Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis

- Texas Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis annectens (Brown, 1950)

Texas Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis annectens - Red-spotted Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis concinnus (Hallowell, 1852)

- New Mexico Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis dorsalis (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Valley Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis fitchi (Fox, 1951)

- California Red-sided Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis infernalis (Blainville, 1835)

- Thamnophis sirtalis lowei (Tanner, 1988)

- Maritime Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis pallidula (Allen, 1899)

- Red-sided Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis (Say, 1823)

- Puget Sound Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis pickeringii (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Bluestripe Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis similis (Rossman, 1965)

- Eastern Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Chicago Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis semifasciatus (Cope, 1892)

- San Francisco Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia (Cope, 1875)

- Texas Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis annectens (Brown, 1950)

- Sumichrast's Garter Snake, Thamnophis sumichrasti (Cope, 1866)

- West Coast Garter Snake, Thamnophis valida

- Mexican Pacific Lowlands Garter Snake, Thamnophis valida celaeno (Cope, 1860)

- Thamnophis valida isabellae (Conant, 1953)

- Thamnophis valida thamnophisoides (Conant, 1961)

- Thamnophis valida valida (Kennicott, 1860)

External links (alphabetical)

- Dutch Gartersnake site with many pictures

- Anapsid.org: Garter Snakes

- Several pictures of a Mexican ribbon snake (Thamnophis proximus rutiloris)

- Thamnophis.com - Garter Snake forum

- The Garter Snake Page

- Garter Snake Caresheet

- Plains Garter Snake - Thamnophis radix Species account from the Iowa Reptile and Amphibian Field Guide

- Eastern Garter Snake - Thamnophis sirtalis Species account from the Iowa Reptile and Amphibian Field Guide. A garter snake is an another name of garden snake..

- SnakePet.info - information on owning pet snakes, including garter snakes

References

- Genus Thamnophis at The Reptile Database