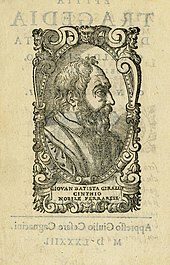

Giovanni Battista Giraldi

Giovanni Battista Giraldi (November[1] 1504 – 30 December 1573) was an Italian novelist and poet. He appended the nickname Cinthio to his name and is commonly referred to by that name (which is also rendered as Cynthius, Cintio or, in Italian, Cinzio).

Biography

[edit]Cinthio was born in Ferrara, then the capital of the Duchy of Ferrara, and educated at the University of Ferrara. In 1525, he became a professor of natural philosophy there. Twelve years later, he succeeded Celio Calcagnini in the chair of belles-lettres.

Between 1542 and 1560 he was a private secretary, first to Ercole II and afterwards to Alfonso II d'Este; but having, in connection with a literary quarrel, lost the favour of his patron, he moved to Mondovì, where he remained as a teacher of literature until 1568. Subsequently, on the invitation of the senate of Milan, he occupied the chair of rhetoric at Pavia until 1573, when, in search of health, he returned to Ferrara, where he later died.

Besides an epic entitled Ercole (1557), in twenty-six cantos, Cinthio wrote nine tragedies, the best known of which, Orbecche, was produced in 1541. The bloodthirsty nature of the play, and its style, are, in the opinion of many of its critics, almost redeemed by occasional bursts of genuine and impassioned poetry.

His literary work was ideologically influenced by the Catholic Reformation. In the theatrical works there appears a vein of experimentation that anticipates some typical elements of taste of the modern European theatre, for example the Elizabethan theatre and baroque styles, where psychological violence and horror are used in function and dramatic action structured in real time.

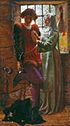

Among the prose works of Cinthio is the Hecatommithi or Gli Ecatommiti, a collection of tales told somewhat after the manner of Boccaccio, but still more closely resembling the novels of Cinthio's contemporary, Matteo Bandello. Something may be said in favour of their professed claim to represent a higher standard of morality. Originally published at Mondovì in 1565, they were frequently reprinted in Italy, while a French translation appeared in 1583 and one in Spanish, with 20 of the stories, in 1590. They have a peculiar interest to students of English literature, for providing the plots of Measure for Measure and Othello. That of the latter, which is to be found in the Hecatommithi, was almost certainly read by Shakespeare in the original Italian;[2] while that of the former is probably to be traced to George Whetstone's Promos and Cassandra (1578), an adaptation of Cinthio's story, and to his Heptamerone (1582), which contains a direct English translation. To Cinthio also must be attributed the plot of Beaumont and Fletcher's Custom of the Country.

References

[edit]- ^ The Bibliophile Dictionary: A Biographical Record of the Great Authors, The Minerva Group, Inc., 2003: "Giraldi, Giovanni Battista"

- ^ Michael Neill, ed. Othello (Oxford University Press), 2006, p. 21–2.

Sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Giraldi, Giovanni Battista". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 44.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Giovanni Battista Giraldi". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Giovanni Battista Giraldi". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Jossa, Stefano, Rappresentazione e scrittura. La crisi delle forme poetiche rinascimentali (1540-1560), Naples: Vivarium, 1996. ISBN 8885239137

External links

[edit] Works by or about Giovanni Battista Giraldi at Wikisource

Works by or about Giovanni Battista Giraldi at Wikisource- [1] Extended contents (not in book) of first (and only) volume of Hecatommithi] transl. into Spanish 1590, digitised by Biblioteca Nacional Espana, bne.es, digital and hard copy page nos

- Massimo Colella, Radici novellistiche e metamorfosi teatrali: Otello da Giraldi Cinzio a Shakespeare, in «Rivista di Letterature moderne e comparate», LXXIV, 2, 2021, pp. 121–144.

- Hecatommithi, Deca Terza, Novella VII: "Un Capitano Moro", di Giovan Battista Giraldi Cinthio (1574), on archive.org

- Gli Ecatommiti, Deca Terza, Novella VII: "Un Capitano Moro", di Giovan Battista Giraldi (1853), on archive.org

- Gli Ecatommiti, Deca Terza, Novella VII: "Un Capitano Moro", di Giovan Battista Giraldi (1853), on archive.org