Grey heron

| Grey heron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. cinerea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ardea cinerea | |

| |

| Range of A. cinerea Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range

| |

The grey heron (Ardea cinerea) is a long-legged predatory wading bird of the heron family, Ardeidae, native throughout temperate Europe and Asia and also parts of Africa. It is resident in much of its range, but some populations from the more northern parts migrate southwards in autumn. A bird of wetland areas, it can be seen around lakes, rivers, ponds, marshes and on the sea coast. It feeds mostly on aquatic creatures which it catches after standing stationary beside or in the water or stalking its prey through the shallows.

Standing up to a metre tall, adults weigh from 1 to 2 kg (2.2 to 4.4 lb). They have a white head and neck with a broad black stripe that extends from the eye to the black crest. The body and wings are grey above and the underparts are greyish-white, with some black on the flanks. The long, sharply pointed beak is pinkish-yellow and the legs are brown.

The birds breed colonially in spring in "heronries", usually building their nests high in trees. A clutch of usually three to five bluish-green eggs is laid. Both birds incubate the eggs for a period of about 25 days, and then both feed the chicks, which fledge when seven or eight weeks old. Many juveniles do not survive their first winter, but if they do, they can expect to live for about five years.

In Ancient Egypt, the deity Bennu was depicted as a heron in New Kingdom artwork. In Ancient Rome, the heron was a bird of divination. Roast heron was once a specially-prized dish; when George Neville became Archbishop of York in 1465, four hundred herons were served to the guests.

Description

The grey heron is a large bird, standing up to 100 cm (39 in) tall and measuring 84–102 cm (33–40 in) long with a 155–195 cm (61–77 in) wingspan.[2] The body weight can range from 1.02–2.08 kg (2.2–4.6 lb).[3] The plumage is largely ashy-grey above, and greyish-white below with some black on the flanks. Adults have the head and neck white with a broad black supercilium that terminates in the slender, dangling crest, and bluish-black streaks on the front of the neck. The scapular feathers are elongated and the feathers at the base of the neck are also somewhat elongated. Immature birds lack the dark stripe on the head and are generally duller in appearance than adults, with a grey head and neck, and a small, dark grey crest. The pinkish-yellow beak is long, straight and powerful, and is brighter in colour in breeding adults. The iris is yellow and the legs are brown and very long.[4]

The main call is a loud croaking "fraaank", but a variety of guttural and raucous noises are heard at the breeding colony. The male uses an advertisement call to encourage a female to join him at the nest, and both sexes use various greeting calls after a pair bond has been established. A loud, harsh "schaah" is used by the male in driving other birds from the vicinity of the nest and a soft "gogogo" expresses anxiety, as when a predator is nearby or a human walks past the colony. The chicks utter loud chattering or ticking noises.[4]

Taxonomy and evolution

Herons are a fairly ancient lineage and first appeared in the fossil record in the Paleogene period; very few fossil herons have been found however. By seven million years ago (the late Miocene), birds closely resembling modern forms and attributable to modern genera had appeared.[5]

Herons are members of the family Ardeidae, and the majority of extant species are in the subfamily Ardeinae and known as true or typical herons. This subfamily includes the herons and egrets, the green herons, the pond herons, the night herons and a few other species. The grey heron belongs in this subfamily and is placed in the genus Ardea, which also includes the cattle egret and the great egret.[5] The grey heron was first described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus who gave it the name Ardea cinerea. The scientific name comes from Latin ardea "heron", and cinerea , "ash-grey" (from cineris ashes).[6]

Four subspecies are recognised:[7]

- A. c. cinerea – Linnaeus, 1758: nominate, found in Europe, Africa, western Asia

- A. c. jouyi – Clark, 1907: found in eastern Asia

- A. c. firasa – Hartert, 1917: found in Madagascar

- A. c. monicae – Jouanin & Roux, 1963: found on islands off Banc d'Arguin, Mauritania.

It is closely related and similar to the North American great blue heron (Ardea herodias), which differs in being larger, and having chestnut-brown flanks and thighs, and to the cocoi heron (Ardea cocoi) from South America that forms a superspecies with. Some authorities believe that the subspecies A. c. monicae should be considered a separate species.[8] It has been known to hybridise with the great egret (Ardea alba), the little egret (Egretta garzetta), the great blue heron and the purple heron (Ardea purpurea).[9] The Australian white-faced heron is often incorrectly called a grey heron.[10] In Ireland, the grey heron is often colloquially called a "crane".[11]

Distribution and habitat

The grey heron has an extensive range throughout most of the Palearctic ecozone. The range of the nominate subspecies A. c. cinerea extends to 70° North in Norway and 66° North in Sweden, but otherwise its northerly limit is around 60° North across the rest of Europe and Asia eastwards as far as the Ural Mountains. To the south, its range extends to northern Spain, France, central Italy, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Iraq, Iran, India and Myanmar (Burma). It is also present in Africa south of the Sahara Desert, the Canary Islands, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and many of the Mediterranean Islands. It is replaced by A. c. jouyi in eastern Siberia, Mongolia, eastern China, Hainan, Japan and Taiwan. In Madagascar and the Aldabra Islands, the subspecies A. c. firasa is found, while the subspecies A. c. monicae is restricted to Mauritania and offshore islands.[4]

Over much of its range, the grey heron is resident, but birds from the more northerly parts of Europe migrate southwards, some remaining in central and southern Europe, others travelling on to Africa south of the Sahara Desert.[4]

Within its range, the grey heron can be found anywhere with suitable watery habitat that can supply its food. The water body needs to be either shallow enough, or have a shelving margin in which it can wade. Although most common in the lowlands it also occurs in mountain tarns, lakes, reservoirs, large and small rivers, marshes, ponds, ditches, flooded areas, coastal lagoons, estuaries and the sea shore. It sometimes forages away from water in pasture, and it has been recorded in desert areas, hunting for beetles and lizards. Breeding colonies are usually near feeding areas but exceptionally may be up to 8 kilometres (5 mi) away, and birds sometimes forage as much as 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the nesting site.[4]

Behavior

The grey heron has a slow flight, with its long neck retracted (S-shaped). This is characteristic of herons and bitterns, and distinguishes them from storks, cranes, and spoonbills, which extend their necks.[4] It flies with slow wing-beats and sometimes glides for short distances. It sometimes soars, circling to considerable heights, but not as often as the stork. In spring, and occasionally in autumn, birds may soar high above the heronry and chase each other, undertake aerial manoeuvres or swoop down towards the ground. The birds often perch in trees, but spend much time on the ground, striding about or standing still for long periods with an upright stance, often on a single leg.[4]

Diet and feeding

Fish, amphibians, small mammals and insects are taken in shallow water with the heron's long bill. It has also been observed catching and killing juvenile birds such as ducklings, and occasionally takes birds up to the size of a water rail.[12] It may stand motionless in the shallows, or on a rock or sandbank beside the water, waiting for prey to come within striking distance. Alternatively, it moves slowly and stealthily through the water with its body less upright than when at rest and its neck curved in an "S". It is able to straighten its neck and strike with its bill very fast.[4]

Small fish are swallowed head first, and larger prey and eels are carried to the shore where they are subdued by being beaten on the ground or stabbed by the bill. They are then swallowed, or have hunks of flesh torn off. For avian prey such as small birds and ducklings, the prey is held by the neck and either suffocated or killed by having its neck snapped with the heron's beak, before being swallowed whole. The bird regurgitates pellets of indigestible material such as fur, bones and the chitinous remains of insects. The main periods of hunting are around dawn and dusk, but it is also active at other times of day. At night it roosts in trees or on cliffs, where it tends to be gregarious.[4]

Breeding

This species breeds in colonies known as heronries, usually in high trees close to lakes, the seashore or other wetlands. Other sites are sometimes chosen, and these include low trees and bushes, bramble patches, reed beds, heather clumps and cliff ledges. The same nest is used year after year until blown down; it starts as a small platform of sticks but expands into a bulky nest as more material is added in subsequent years. It may be lined with smaller twigs, strands of root or dead grasses, and in reed beds, it is built from dead reeds. The male usually collects the material while the female constructs the nest. Breeding activities take place between February and June. When a bird arrives at the nest, a greeting ceremony occurs in which each partner raises and lowers its wings and plumes.[11] In continental Europe, and elsewhere, nesting colonies sometimes include nests of the purple heron and other heron species.[4]

Courtship involves the male calling from the chosen nesting site. On the arrival of the female, both birds participate in a stretching ceremony, in which each bird extends its neck vertically before bringing it backwards and downwards with the bill remaining vertical, simultaneously flexing its legs, before returning to its normal stance. The snapping ceremony is another behaviour where the neck is extended forward, the head is lowered to the level of the feet and the mandibles are vigorously snapped together. This may be repeated twenty to forty times. When the pairing is settled, the birds may caress each other by attending to the other bird's plumage. The male may then offer the female a stick which she incorporates into the nest. At this, the male becomes excited, further preening the female and copulation takes place.[4]

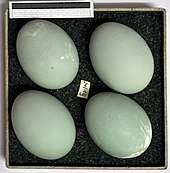

The clutch of eggs usually numbers three to five, though as few as two and as many as seven eggs have been recorded. The eggs have a matt surface and are greenish-blue, averaging 60 mm × 43 mm (2.36 in × 1.69 in). The eggs are normally laid at two-day intervals and incubation usually starts after the first or second egg has been laid. Both birds take part in incubation and the period lasts for about twenty-five days. Both parents bring food for the young. At first the chicks seize the adult's bill from the side and extract regurgitated food from it. Later the adult disgorges the food at the nest and the chicks squabble for possession. They fledge at seven to eight weeks. There is usually a single generation each year, but two broods have been recorded.[4]

The oldest recorded bird lived for twenty-three years but the average life expectancy in the wild is about five years. Only about a third of juveniles survive into their second year, many falling victim to predation.[11]

City life

Grey herons have the ability to live in cities where habitats and nesting space are available. In the Netherlands, the grey heron has established itself over the past decades in great numbers in urban environments. In cities such as Amsterdam, they are ever present and well adapted to modern city life. They hunt as usual, but also visit street markets and snackbars. Some individuals make use of people feeding them at their homes or share the catch of recreational fishermen. Similar behaviour on a smaller scale has been reported in Ireland.[13] Garden ponds stocked with ornamental fish are attractive to herons, and may provide young birds with a learning opportunity on how to catch easy prey.[14]

Herons have been observed visiting water enclosures in zoos, such as spaces for penguins, otters, pelicans, and seals, and taking food meant for the animals on display.[15][16][17][18]

Predators and parasites

Being large birds with powerful beaks, grey herons have few predators as adults, but the eggs and young are more vulnerable. The adult birds do not usually leave the nest unattended, but may be lured away by marauding crows or kites.[19] A dead grey heron found in the Pyrenees is thought to have been killed by an otter. The bird may have been weakened by harsh winter weather causing scarcity of its prey.[20]

A study performed by Sitko and Heneberg in the Czech Republic between 1962 and 2013 suggested that central European grey herons host 29 species of parasitic worms. The dominant species consisted of Apharyngostrigea cornu (67% prevalence), Posthodiplostomum cuticola (41% prevalence), Echinochasmus beleocephalus (39% prevalence), Uroproctepisthmium bursicola (36% prevalence), Neogryporhynchus cheilancristrotus (31% prevalence), Desmidocercella numidica (29% prevalence) and Bilharziella polonica (5% prevalence). Juvenile grey herons were shown to host fewer species, but the intensity of infection was higher in the juveniles than in the adult herons. Of the digenean flatworms found in central European grey herons, 52% of the species likely infected their definitive hosts outside central Europe itself, in the pre-migratory, migratory, or wintering quarters, despite the fact that a substantial proportion of grey herons do not migrate to the south.[21]

In human culture

In Ancient Egypt, the bird deity Bennu, associated with the sun, creation, and rebirth, was depicted as a heron in New Kingdom artwork.[22]

In Ancient Rome, the heron was a bird of divination that gave an augury (sign of a coming event) by its call, like the raven, stork, and owl.[23]

Roast heron was once a specially-prized dish in Britain for special occasions such as state banquets. For the appointment of George Neville as Archbishop of York in 1465, four hundred herons were served to the guests. Young birds were still being shot and eaten in Romney Marsh in 1896. Two grey herons feature in a stained glass window of the church in Selborne, Hampshire.[24]

The English surnames Earnshaw, Hernshaw, Herne, and Heron all derive from the heron, the suffix -shaw meaning a wood, referring to a place where herons nested.[25]

References

- ^ BirdLife International (2012). "Ardea cinerea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. IUCN: e.T22696993A40287322. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22696993A40287322.en. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Grey heron (Ardea cinerea)". ARKive. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ Dunning Jr., John B., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Witherby, H. F., ed. (1943). Handbook of British Birds, Volume 3: Hawks to Ducks. H. F. and G. Witherby Ltd. pp. 125–133.

- ^ a b "Heron Taxonomy and Evolution". Heron Conservation. IUCN Heron Specialist Group. 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 54, 107. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Gill, F.; Donsker, D., eds. (2014). "IOC World Bird List (v 4.4)". doi:10.14344/IOC.ML.4.4.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Martínez-Vilalta, A.; Motis, A.; Kirwan, G.M. (2014). "Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Grey Heron: Ardea cinerea Linnaeus, 1758". Avibase. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Pizzey, Graham; Knight, Frank (1997). Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Sydney, Australia: HarperCollinsPublishers. p. 111. ISBN 0-207-18013-X.

- ^ a b c "Grey herons". AvianWeb. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Pistorius, P.A. (2008). "Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea) predation on the Aldabra White-throated Rail (Dryolimnas cuvieri aldabranus)". Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 120 (3): 631–632. doi:10.1676/07-101.1.

- ^ The heron's city life is documented in the Dutch documentary Schoffies (Hoodlums), shot in Amsterdam.

- ^ "Herons and garden fish ponds". RSPB. 3 June 2004. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ "Graureiher". Tiergarten Schoenbrunn. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Rosie. "Oi, hands off our fish! Cheeky heron flies in as penguins enjoy new Olympic diving pool". Daily Mail Online. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ "Birdworld Animals". Birdworld. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Mallison, Heinrich. "Interspecific prey theft in extant theropod dinosaurs – Ardea vs. Spheniscus". Dinosaur Paleo. Humboldt University Berlin. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ Kwong Wai Chong (5 January 2011). "Nesting grey herons: predation". Bird Ecology Study Group. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Ruiz-Olmo, Jordi; Marsol, Rosa (2002). "New Information on the Predation of Fish Eating Birds by the Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra)". IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin. 19 (2): 103–106.

- ^ Sitko, J.; Heneberg, P. (2015). "Composition, structure and pattern of helminth assemblages associated with central European herons (Ardeidae)". Parasitology International. 64: 100–112. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2014.10.009.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- ^ Jonson, Ben; Orgel, Stephen (1969). The Complete Masques. Yale University Press. p. 553. ISBN 978-0-300-10538-4.

- ^ Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. Chatto & Windus. pp. 51–56. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Bardsley, Ch. W. E. (1901). A dictionary of English and Welsh surnames. Henry Frowde. p. 377. ISBN 978-5-87114-401-5.