Guernsey Martyrs

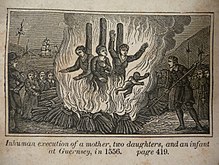

The Guernsey Martyrs were three women who were burned at the stake for their Protestant beliefs, in Guernsey, Channel Islands, in 1556 during the Marian persecutions.

Trial

[edit]Guillemine Gilbert and Perotine Massey were sisters, who lived with their mother, Catherine Cauchés (sometimes given as "Katherine Cawches"). Perotine was the wife of a Norman Calvinist minister, who was in London, possibly to avoid persecution. The three women were brought to court on a charge of receiving a stolen goblet. Although they were found to be not guilty of that charge, it emerged that their religious views were contrary to those required by the church authorities. They were returned to prison in Castle Cornet and later found guilty of heresy by an ecclesiastical court held in the Town Church and handed over to the Royal Court for sentencing where they were condemned to death.[1]

Execution

[edit]The execution was carried out on or around 18 July 1556.[2]: 39 All three were burnt on the same fire; they ought to have been strangled beforehand, but the rope broke before they died and they were thrown into the fire alive.[3] John Foxe recorded that Perotine was "great with child" and that "the belly of the woman burst asunder by the vehemence of the flame, the infant, being a fair man-child, fell into the fire". The baby was rescued by a W. House and laid on the grass,[1] taken by the Provost to the Bailiff, Hellier Gosselin who ordered that "it should be carried back again, and cast into the fire".[2][4]

Legacy

[edit]On the death of Queen Mary (1558), the Bailiff and the Roman Catholic élite of the island were subjected to a series of commissions and investigations encompassing not only the circumstances of the execution of the women, but also embezzlement; James Amy, the Dean, was committed to prison in Castle Cornet and dispossessed of his living. Gosselin was dismissed from his post in 1562 but along with the Jurats managed to obtain a pardon from Elizabeth I.[2]: 40

Reactions to the executions played a role in the rise of Calvinism in the Channel Islands.[5]

In 1567, Thomas Harding criticised Foxe's account, not for his description of the event, for which Foxe quotes eye-witnesses and official documents, but on the grounds that Perotine Massey was responsible for the death of her own child; had she revealed in court that she was pregnant, "pleading the belly", the execution would have had to have been postponed until after the birth.[6]

A memorial plaque to the martyrs can be found on the Tower Hill steps in Saint Peter Port, near the site of the execution. It was unveiled at a commemorative service on 24 April 1999.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Lempriére, Raoul (1974). History of the Channel Islands. Robert Hale Ltd. p. 51. ISBN 978-0709142522.

- ^ a b c Tupper, Ferdinand Brock. The Chronicles of Castle Cornet. Stephen Barbet 1851.

- ^ Guernsey Museums and Galleries: The Story of Catherine Cauchés and her Daughters Archived 2010-09-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Acts And Monuments Of The Christian Church By John Foxe: 350. Katharine Cawches, Guillemine Gilbert, Perotine Massey, and an Infant, the Son of Perotine Massey

- ^ Compare: Ogier, Darryl Mark (1997), Reformation and Society in Guernsey, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-0851156033 (p. 62)

- ^ Levin, Carole (1981), Women in The Book Of Martyrs as Models of Behavior in Tudor England, University of Nebraska - Lincoln (pp. 202 - 203)

- ^ "La Villiaze Evangelical Congregational Church: The Guernsey Martyrs Memorial". Archived from the original on 2016-02-14. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

Further reading

[edit]- "Murder not then the fruit within my womb": Shakespeare's Joan, Foxe's Guernsey Martyr, and Women Pleading Pregnancy in Early Modern English History and Culture[permanent dead link]

- Seizing the stake: Female martyrdom in England during the Reformation

- Women in The Book Of Martyrs as Models of Behavior in Tudor England

- Night Seasons: Trauma, history, and the uses of women's martyrdom in seventeenth-century Puritan literature

- Heresy and Infanticide in ‘Catholic' Guernsey

- 1556 deaths

- 1556 in Europe

- 16th-century Protestant martyrs

- Executed British people

- Executed children

- Groups of Christian martyrs of the Early Modern era

- Guernsey Protestants

- Guernsey women

- History of Guernsey

- Martyred groups

- People executed by the Kingdom of England by burning

- People executed for heresy

- People executed under Mary I of England

- Protestant martyrs of England