HMS St Vincent (1908)

St Vincent at the Coronation Review, Spithead, 24 June 1911

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Saint Vincent |

| Namesake | Admiral of the Fleet John Jervis, Earl of St Vincent |

| Ordered | 26 October 1907 |

| Laid down | 30 December 1907 |

| Launched | 10 September 1908 |

| Commissioned | 3 May 1910 |

| Decommissioned | March 1921 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 1 December 1921 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 19,700 long tons (20,000 t) (normal) |

| Length | 536 ft (163.4 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 84 ft (25.6 m) |

| Draught | 28 ft (8.5 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,900 nmi (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 756–835 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

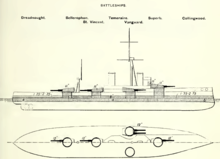

HMS St Vincent was the lead ship of her class of three dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Navy in the first decade of the 20th century. She spent her whole career assigned to the Home and Grand Fleets and often served as a flagship. Aside from participating in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, during which she damaged a German battlecruiser, her service during World War I generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea. The ship was deemed obsolete after the war and was reduced to reserve and used as a training ship. St Vincent was sold for scrap in 1921.

Design and description

The design of the St Vincent class was derived from that of the previous Template:Sclass-. St Vincent had an overall length of 536 feet (163.4 m), a beam of 84 feet (25.6 m),[1] and a normal draught of 28 feet (8.5 m).[2] She displaced 19,700 long tons (20,000 t) at normal load and 22,800 long tons (23,200 t) at deep load. In 1911 her crew numbered 756 officers and enlisted men and 835 in 1915.[3]

Machinery

St Vincent was powered by 2 sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each driving two shafts, using steam from eighteen Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The turbines were rated at 24,500 shp (18,300 kW) and intended to reach a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). During her sea trials on 17 December 1909, the ship reached a top speed of 21.67 knots (40.13 km/h; 24.94 mph) from 28,218 shp (21,042 kW). She had a range of 6,900 nautical miles (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4]

Armament

The St Vincent class was equipped with ten breech-loading (BL) 12-inch (305 mm) Mk XI guns in five twin gun turrets, three along the centreline and the remaining two as wing turrets. The secondary, or anti-torpedo boat armament, comprised twenty BL 4-inch (102 mm) Mk VII guns. Two of these guns were each installed on the roofs of the fore and aft centreline turrets and the wing turrets in unshielded mounts, and the other ten were positioned in the superstructure. All guns were in single mounts.[3] The ships were also fitted with three 18-inch torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and the third in the stern.[2]

Armour

The St Vincent-class ships had a waterline belt of Krupp cemented armour (KC) that was 10 inches (254 mm) thick between the fore and aftmost barbettes that reduced to a thickness of 2 inches (51 mm) before it reached the ships' ends. Above this was a strake of armour 8 inches (203 mm) thick. Transverse bulkheads 5 to 8 inches (127 to 203 mm) inches thick terminated the thickest parts of the waterline and upper armour belts once they reached the outer portions of the endmost barbettes.[5]

The three centreline barbettes were protected by armour 9 inches (229 mm) thick above the main deck that thinned to 5 inches (127 mm) below it. The wing barbettes were similar except that they had 10 inches of armour on their outer faces. The gun turrets had 11-inch (279 mm) faces and sides with 3 inches (76 mm) roofs. The three armoured decks ranged in thicknesses from .75 to 3 inches (19 to 76 mm). The front and sides of the forward conning tower were protected by 11-inch plates, although the rear and roof were 8 inches and 3 inches thick respectively.[6]

Alterations

The guns on the forward turret roof were removed in 1911–12 and the upper forward pair of guns in the superstructure were removed in 1913–14. In addition, gun shields were fitted to all guns in the superstructure and the bridge structure was enlarged around the base of the forward tripod mast. During the first year of the war, a fire-control director was installed high on the forward tripod mast. Around the same time, the base of the forward superstructure was rebuilt to house four 4-inch guns and the turret-top guns were removed, which reduced her secondary armament to a total of fourteen guns. In addition a pair of 3-inch anti-aircraft (AA) guns were added.[7]

By April 1917, St Vincent mounted thirteen 4-inch anti-torpedo boat guns as well as single 4-inch and 3-inch AA guns. Approximately 50 long tons (51 t) of additional deck armour had been added after the Battle of Jutland and the ship was modified to operate a kite balloon. In 1918 a high-angle rangefinder was fitted and the stern torpedo tube was removed before the end of the war.[7]

Construction and career

St Vincent, named after Admiral of the Fleet John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent,[8] was ordered on 26 October 1907.[9] She was laid down at Portsmouth Royal Dockyard on the same date; launched on 10 September 1908 and completed in May 1909. Including her armament, her cost is variously quoted at £1,579,970[3] or £1,754,615.[10] She was commissioned on 3 May 1910 and assigned as the junior flagship of the 1st Division of the Home Fleet. She was commanded by Captain Douglas Nicholson and was present in Torbay when King George V visited the fleet in late July. St Vincent also participated in the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead on 24 June 1911. On 1 May 1912 the 1st Division was renamed the 1st Battle Squadron. The ship participated in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead before beginning a lengthy refit late in the year.[9]

On 21 April 1914, she was recommissioned and resumed her role as the flagship of the second-in-command of the 2nd Division, 1st Battle Squadron,[9] under the command of Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas.[11] Between 17 and 20 July, she took part in a test mobilisation and fleet review. On 29 July she sailed to the fleet's war station at Scapa Flow and began the patrols and training exercises that constituted the greater part of her service after the declaration of war on 4 August. She was briefly based (22 October to 3 November) with the greater part of the fleet at Lough Swilly while the defences at Scapa were strengthened. King George V inspected all of the personnel of the 2nd Division aboard St Vincent during his visit to Scapa on 8 July 1915. She became a private ship in November when she was relieved by Colossus as flagship.[9]

Battle of Jutland

St Vincent, under the command of Captain William Fisher, was assigned to the 5th Division of the 1st Battle Squadron at the Battle of Jutland. Shortly after 14:20,[Note 1] Fisher semaphored the Grand Fleet's flagship, Iron Duke, that his ship was monitoring strong radio signals on the frequency used by the German High Seas Fleet that implied the Germans were nearby. Detection of further signals was transmitted at 14:52.[12]

As the Grand Fleet began deploying from columns into line of battle beginning at 18:15, the 5th Division was near the rear and St Vincent, the twentieth ship from the front, was briefly forced to stop to avoid overrunning ships further forward as the fleet had been forced to slow to 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) to allow the battlecruisers to assume their position at the head of the line. During the first stage of the general engagement, the ship fired a few salvos from her main guns at the crippled light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden from 18:33, although the number of hits made, if any, is unknown. Between 18:40 and 19:00 the ship turned away twice from what were thought to be torpedoes that stopped short of the ship. From 19:10 St Vincent began firing at what was identified as a German battleship, but proved to be the battlecruiser SMS Moltke, hitting her target twice before she disappeared into the mist. The first armor-piercing, capped (APC) shell was probably a ricochet and struck the upper hull abreast the bridge. It wrecked the sickbay and slightly damaged the surrounding superstructure and hull which caused some minor flooding. One man in the conning tower was wounded by a splinter. The second hit penetrated the rear armor of the superfiring turret at the rear of the ship, wrecking it and starting a small fire that was easily extinguished by the crew. This was the last time that St Vincent fired her guns during the battle. The ship fired a total of 90 APC and 8 Common Pointed, Capped twelve-inch shells during the battle.[13]

Shortly after the battle, she was transferred to the 4th Battle Squadron.[9] On 24 April 1918, St Vincent was under repair at Invergordon when she, and the dreadnought Hercules were ordered north to reinforce the forces based at Scapa Flow and the Orkneys when the High Seas Fleet sortied north for the last time to intercept a convoy to Norway. She was unable to comply with the order before the Germans turned back after Moltke suffered engine damage.[14] The ship was present at Rosyth when the German fleet surrendered on 21 November. In March 1919, she was reduced to reserve and became a gunnery training ship at Portsmouth. St Vincent became flagship of the Reserve Fleet in June and was relieved as gunnery training ship in December when she was transferred to Rosyth. There she remained until listed for disposal in March 1921. She was sold to the Stanlee Shipbreaking & Salvage Co. for scrap on 1 December 1921 and towed to Dover for demolition in March 1922.[9]

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Burt, pp. 75–76

- ^ a b Preston, p. 125

- ^ a b c Burt, p. 76

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 80

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 78; Parkes, p. 503

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 78; Parkes, p. 504

- ^ a b Burt, p. 81

- ^ Silverstone, p. 267

- ^ a b c d e f Burt, p. 86

- ^ Parkes, p. 503

- ^ Corbett, p. 438

- ^ Burt, p. 86; Gordon, p. 416

- ^ Campbell, pp. 146, 157, 167, 205, 208, 232–34, 349

- ^ Newbolt, pp. 235–38

Bibliography

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- Corbett, Julian. Naval Operations to the Battle of the Falklands. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. I (2nd, reprint of the 1938 ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-256-X.

- Gordon, Andrew (2012). The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-336-9.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. V (reprint of the 1931 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-255-1.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.