Heaving to

In sailing, heaving to (to heave to and to be hove to) is a way of slowing a sailboat's forward progress, as well as fixing the helm and sail positions so that the boat does not actively have to be steered. It is commonly used for a "break"; this may be to wait for the tide before proceeding, to wait out a strong or contrary wind. For a solo or shorthanded sailor it can provide time to go below deck, to attend to issues elsewhere on the boat, or for example to take a meal break.[1][2]

The term is also used in the context of vessels under power and refers to bringing the vessel to a complete stop. For example, in waters over which the United States has jurisdiction the Coast Guard may, under 14 U.S.C. § 89, demand that a boat "heave to" in order to enforce federal laws.[3]

Hove to

A sailing vessel is hove to when it is at or nearly at rest because the driving action from one or more sails is approximately balanced by the drive from the other(s). This always involves 'backing' one or more sails, so that the wind is pressing against the forward side of the cloth, rather than the aft side as it normally would for the sail to drive the vessel forwards. On large square rigged, multi-masted vessels the procedures can be quite complex and varied, but on a modern two-sailed sloop, there is only the jib and the mainsail. A cutter may have more than one headsail, and a ketch, yawl or schooner may have more than one sail on a boom. In what follows, the jibs and boomed sails on such craft can either be treated as one of each, or lowered for the purposes of reduced windage, heel or complexity when heaving to for any length of time.

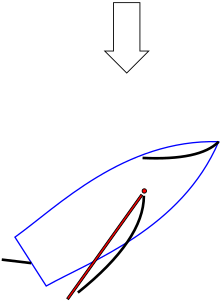

When a sloop is hove to, the jib is backed. This means that its windward sheet is tight holding the sail to windward. The mainsail sheet is often eased, or the mainsail reefed, to reduce forward movement, or 'fore-reaching'. The rudder is placed so that, should the boat make any forward movement, it will be turned into the wind, so as to prevent forward momentum building up. In a centerboard boat the centerboard will be partially raised and the tiller held down hard.

Heaving to

For a sloop sailing along normally, either of two maneuvers will render the sailboat to be hove to.

First, the jib can be literally heaved to windward, using the windward sheet and releasing the other. Then the rudder would be put across so as to turn gently towards the wind. Without the drive of the jib, and allowing time for momentum to die down, the sailboat will be unable to tack and will stop hove to. This method may be preferable when broad reaching or running before a strong wind in a heavy sea and the prospect of tacking through the wind in order to heave to may not appeal. Bearing away from the wind so that the headsail is blanketed by the mainsail can make it easier to haul in the windward sheet.

Alternatively, the vessel can simply be turned normally to tack through the wind, without freeing the jibsheet. The mainsail should self-tack onto the other side, but the jib is held aback. Finally the rudder is put the other way, as if trying to tack back again. Without the drive of the jib, she cannot do this and will stop hove to. This method is fast to implement and is recommended by sail training bodies such as the RYA as a 'quick stop' reaction to a man overboard emergency, for sailing boats that have an engine available for further maneuvers to approach and pick up the casualty.[4]

Finally, in either case, the tiller or wheel should be lashed so that the rudder cannot move again, and the mainsheet adjusted so that the boat lies with the wind ahead of the beam with minimal speed forward. Usually this involves easing the sheet slightly compared to a closehauled position, but depending on the relative sizes of the sails, the shape and configuration of the keel and rudder and the state of the wind and sea, each skipper will have to experiment. After this the boat can be left indefinitely, only keeping a lookout for other approaching vessels.

When hove to, the boat will heel, there will be some drift to leeward and some tendency to forereach, so adequate seaway must be allowed for. In rough weather, this leeway can actually leave a 'slick' effect to windward, in which the waves are smaller than elsewhere. This can make a rest or meal break a little more comfortable at times.

To come out from the hove-to position and get under way again, the tiller or wheel is unlashed and the windward jibsheet is released, hauling in the normal leeward one. Bearing off the wind using the rudder will get the boat moving and then she can be maneuvered onto any desired course. It is important when choosing the tack, heaving to, and remaining hove to, in a confined space that adequate room is allowed for these maneuvers.

Depending on the underwater configuration and relative sail areas, some vessels cannot be left hove to particularly in rough weather. If the action of the wind and waves is capable of pushing the bow off the wind sufficiently, it is possible that the boat will gybe and sail herself around in part of a rather violent circle with the rudder lashed. More traditional hulls with longer keels tend to heave to more calmly, those with deep dagger or blade keels and flat bottoms tend to be more skittish. Large genoas do not help with heaving to, compared to smaller jibs, as they wrap aft of the shrouds and add to the forward drive. Some mainsails need easing, others need reefing and some may need to be hardened in to achieve a stable heave-to.

Heaving to as a storm tactic

During the ill fated 1979 Fastnet race, of 300 yachts, 158 chose to adopt storm tactics; 86 'lay ahull', whereby the yacht adopts a 'beam on' attitude to the wind and waves; 46 ran before the wind under bare poles or trailing warps/sea anchors and 26 heaved to. 100 yachts suffered knock downs, 77 rolled (that is turtled) at least once. Not one of the hove to yachts were capsized or suffered any serious damage.[5] The 'heave to' maneuver is described in the story of the first Golden Globe yacht race of 1968.[6]

References

- ^ www.sailingusa.info/points_of_sail.htm Archived June 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Heavy weather conditions at sea (pictures and further explanation)". Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "US Coast Guard Law Enforcement" (PDF). Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Pearson, Malcolm (2007). Reeds skipper's handbook: for sail and power. London: Adlard Coles Nautical. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-7136-8338-7.

- ^ Pardey, Lin (2008). Storm Tactics Handbook, 3rd Ed., Modern methods of heaving-to for survival in extreme conditions. Arcata, California: Pardey Books. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-92921-447-1.

- ^ Nichols, Peter (2002). A Voyage For Madmen. London: Profile Books. p. 320. ISBN 978-1861974655.