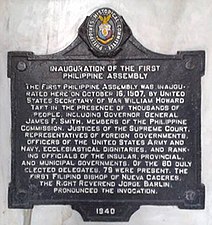

Historical marker

It has been suggested that this article be merged with Commemorative plaque. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2016. |

A historical marker or historic marker is an indicator such as a plaque or sign to commemorate an event or person of historic interest and to associate that point of interest with a specific locale one can visit.[1]

Description

Historical markers are put on display by the owners of sites listed by national agencies concerned with historic preservation such as the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the National Register of Historic Places[2] (in the United States), the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty[3] (in the United Kingdom), An Taisce[4] (in Ireland), National Historical Commission of the Philippines (in the Philippines), and the National Trusts of other countries.

Other historical markers are created by local municipalities, non-profit organizations, companies, or individuals. In addition to geographically defined regions, individual organizations, such as E Clampus Vitus or the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, can choose to maintain a national set of historical markers that fit a certain theme.[5]

History

The Royal Society of Arts established the first scheme in the world for historical commemoration on plaques in 1866.[6]

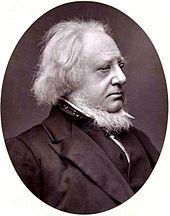

The scheme was established under the influence of the British politician William Ewart and the civil servant Henry Cole.[7] The first plaque was unveiled in 1867 to commemorate Lord Byron at his birthplace, 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square. The earliest historical marker to survive, commemorates Napoleon III in King Street, St James's, and was also put up in 1867.[8]

The original plaque colour was blue, but this was changed by the manufacturer Minton, Hollins & Co to chocolate brown to save money.[9] In 1901, the scheme was first taken over by the local government authority - the London County Council.[10]

Examples

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (March 2011) |

The criteria and circumstances through which a party administers the distribution of historical markers varies. For example, the "Preservation Worcester" program in Worcester, Massachusetts allows a person to register their house or other structure of least fifty years of age if the building is well preserved, with retention of its original character and importance to the architectural, cultural or historical nature of the local neighborhood. One then pays a fee ($185 to $225) to receive the historical marker itself.[11]

In the same state, the Boston neighborhood of Charlestown, Massachusetts has its own local association to administer historical markers.[12] Other historical markers in and around Boston are administered by agencies such as The Bostonian Society[13] or are associated with sites such as those along the Freedom Trail, the Black Heritage Trail, and the Emerald Necklace.[14]

Other examples of mostly locally generated historical markers in the United States include the plaque outside the Alaska Governor's Mansion made by the Alaska Centennial Commission's historical markers program,[15] the historical markers of State Historic Marker Council in Florida,[16] the markers placed by various agencies in Georgia (of which one source mentions 3,292 different historical markers[1]), in Indiana, where it is illegal to create a historical marker in the "state format" without first getting official approval from that state's historical bureau,[17] historical markers in Kansas erected by the Kansas Historical Society and the Kansas Department of Transportation,[18] the Roadside Historic Marker Program in Maryland administered by the Maryland Historical Trust,[19] the State Historic Marker Program of New York (begun in 1926 to commemorate the Sequicentennial of the American Revolution),[20] the historic markers placed as recently as 2008 in Sussex County, New Jersey,[21] the New Mexico historical markers printed in white letters on a brown background by the New Mexico Department of Transportation,[22] the historical markers of North Carolina (the Historical Publications Section of the state Office of Archives and History publishes a Guide to North Carolina Highway Historical Markers),[23] the more than 1200 historical markers of Ohio (all of which are now made in a Marietta, Ohio workshop),[24] and over 550 official state markers in Wisconsin.[25]

Blue plaques are the principal type of historical markers found throughout England and are the closest thing there is to a historical marker system in that country. An example is the blue plaque scheme run by English Heritage in London, although these were originally erected in a variety of shapes and colors. The National Trust (which is a non-profit charity organization unlike English Heritage and English Heritage properties) has its own similar markers as well.[26][27]

However, not all historical markers in the United Kingdom are blue, and many are not ceramic. There are commemorative plaque schemes in Bath, Edinburgh, Brighton, Liverpool, Loughton, and elsewhere—some of which differ from the familiar blue plaque. A scheme in Manchester uses color-coded plaques to commemorate figures, with each of the colors corresponding to the person's occupation. The Dead Comics' Society installs blue plaques to commemorate the former residences of well-known comedians, including those of Sid James and John Le Mesurier. In 2003, the London Borough of Southwark started a plaque scheme which included living people in the awards. Even in London, the Westminster City Council runs a green plaque scheme which is run alongside that of the blue plaque scheme administered by English Heritage. Other schemes are run by civic societies, district or town councils, or local history groups, and often operate with different criteria.[26][27] In 2010, British tabloid The Sun placed a red coloured plaque outside the Snappy Snaps store in Hampstead, North London where singer George Michael crashed in the early hours of Sunday 4 July 2010. The newspaper stated it planned to put similar plaques in sites around the UK to mark events that had proved popular in the UK Tabloid Press.[28]

Gallery

Some sample images of historical markers from different places:

See also

Austria

Belgium

Canada

Chile

France

Germany

Hong Kong

- Declared monuments of Hong Kong

- List of Grade I historic buildings in Hong Kong

- List of Grade II historic buildings in Hong Kong

- List of Grade III historic buildings in Hong Kong

Italy

Netherlands

New Zealand

Singapore

Switzerland

- Kulturgüterschutz — or: Protection des biens culturels; Cultural heritage protection in Switzerland; or Protezione dei beni culturali

Philippines

- Historical markers all over Philippines

United Kingdom

- Blue plaques programme — all U.K.

- List of blue plaques

- Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest

- National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty — England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

- National Trust for Scotland — Scotland

United States

- National Register of Historic Places (NRHP)

- National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Historical markers posted at U.S. state and/or municipal levels (examples):

- California Historical Landmark — of statewide historical significance, by state

- New York State Historic Markers — of statewide historical significance, by state

- California Points of Historical Interest — of local (city or county) significance, by state

- Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument — by city

- San Francisco Designated Landmarks — by city

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission Designated Landmarks — by city

- North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, part of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources -- by state

- West Virginia, significance in state or local prehistory (archaeology), history, natural history, architecture, or cultural life - by state

Bibliography

- James Loewen, Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong, 1999.

- English Heritage, Blue Plaques: A Guide to the Scheme, 2002

- Nick Rennison, The London Blue Plaque Guide, 2003

- Derek Sumeray, Discovering London Plaques

- Derek Sumeray, Track the Plaque, 2003

References

- ^ a b "Historic Markers Across Georgia". Latitude 34 North. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "The National Trust". Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "An Taisce". National Trust for Ireland. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Making their markers". The News & Observer. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ Hansard vol 172 17 July 1863 quoted in 'The commemoration of historians under the blue plaque scheme in London' by author Howard Spencer

- ^ "History of the Blue Plaques Scheme". English Heritage. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ "About blue plaques". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ "The Blue Plaque Design". English Heritage. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ "Preservationworcester.org". Preservationworcester.org. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ "Charlestownpreservation.org". Charlestownpreservation.org. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ 2007 Catalogue For Philanthropy

- ^ "Boston National Historic Park". Nps.gov. 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ "Alaska Historic Markers". Waymarking.com. 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ Florida Heritage & Preservation Archived August 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Historical Marker FAQs". In.gov. 2009-06-16. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ "Kansas Historical Markers". Kshs.org. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ Maryland Historical Trust [dead link]

- ^ "New York State Museum". Nysm.nysed.gov. 1998-12-01. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ "Sussex County News and Information". Sussex.nj.us. 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ New Mexico Department of Transportation [dead link]

- ^ News Observer (July 26, 2006)

- ^ "Manufacturing Ohio's Historic Markers". Touring-ohio.com. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ "Wisconsin Historical Society". Wisconsinhistory.org. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ a b Markeroni.com, Information about historical markers and historical plaques, and historic preservation in England, British Isles.

- ^ a b "English Heritage". English Heritage. 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ "The Sun marks the dented shop front where stoned George Michael crashed", The Sun, accessed 2010-09-18.