History of climate change science: Difference between revisions

OKIsItJustMe (talk | contribs) m Updated quote to use {{CO2}} |

LovelyButz (talk | contribs) →Scientists increasingly predicting warming, 1970s: This properly captures the section content |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

By the 1960s, [[aerosol]] pollution ("smog") had become a serious local problem in many cities, and some scientists began to consider whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution could affect global temperatures. Scientists were unsure whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution or warming effect of greenhouse gas emissions would predominate, but regardless, began to suspect the net effect could be disruptive to climate in the matter of decades. In his 1968 book ''[[The Population Bomb]]'', [[Paul R. Ehrlich]] wrote "the greenhouse effect is being enhanced now by the greatly increased level of carbon dioxide... [this] is being countered by low-level clouds generated by contrails, dust, and other contaminants... At the moment we cannot predict what the overall climatic results will be of our using the atmosphere as a garbage dump."<ref>{{cite book |author=Paul R. Ehrlich |title=The Population Bomb |year=1968 |page=52 }}</ref> |

By the 1960s, [[aerosol]] pollution ("smog") had become a serious local problem in many cities, and some scientists began to consider whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution could affect global temperatures. Scientists were unsure whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution or warming effect of greenhouse gas emissions would predominate, but regardless, began to suspect the net effect could be disruptive to climate in the matter of decades. In his 1968 book ''[[The Population Bomb]]'', [[Paul R. Ehrlich]] wrote "the greenhouse effect is being enhanced now by the greatly increased level of carbon dioxide... [this] is being countered by low-level clouds generated by contrails, dust, and other contaminants... At the moment we cannot predict what the overall climatic results will be of our using the atmosphere as a garbage dump."<ref>{{cite book |author=Paul R. Ehrlich |title=The Population Bomb |year=1968 |page=52 }}</ref> |

||

== Global cooling vs. global warming == |

|||

== Scientists increasingly predicting warming, 1970s == |

|||

[[Image:Global Cooling Map.png|thumb|left|Mean temperature anomalies during the period 1965 to 1975 with respect to the average temperatures from 1937 to 1946. This dataset was not available at the time.]] |

[[Image:Global Cooling Map.png|thumb|left|Mean temperature anomalies during the period 1965 to 1975 with respect to the average temperatures from 1937 to 1946. This dataset was not available at the time.]] |

||

{{ Main | global cooling }} |

{{ Main | global cooling }} |

||

Revision as of 06:56, 5 March 2011

The history of the scientific discovery of climate change began in the early 19th century when natural changes in paleoclimate were first suspected and the natural greenhouse effect first identified. In the late 19th century, scientists first argued that human emissions of greenhouse gases could change the climate, but the calculations were disputed. In the 1950s and 1960s, scientists increasingly thought that human activity could change the climate on a timescale of decades, but were unsure whether the net impact would be to warm or cool the climate. During the 1970s, scientific opinion increasingly favored the warming viewpoint. In the 1980s the consensus position formed that human activity was in the process of warming the climate, leading to the beginning of the modern period of global warming science summarized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Paleoclimate change and the natural greenhouse effect, early and mid 1800s

Prior to the 18th century, scientists had not suspected that prehistoric climates were different from the modern period. By the late 18th century, geologists found evidence of a succession of geological ages with changes in climate. There were various competing theories about these changes, and James Hutton, whose ideas of cyclic change over huge periods of time were later dubbed uniformitarianism, was among those who found signs of past glacial activity in places too warm for glaciers in modern times.[1]

Although he wasn't a scientist, in 1815 Jean-Pierre Perraudin described for the first time how glaciers might be responsible for the giant boulders seen in alpine valleys. As he hiked in the Val de Bagnes, he noticed giant granite rocks that were scattered around the narrow valley. He knew that it would take an exceptional force to move such large rocks. He also noticed how glaciers left stripes on the land, and concluded that it was the ice that had carried the boulders down into the valleys.[2]

His idea was initially met with disbelief. Jean de Charpentier wrote, "I found his hypothesis so extraordinary and even so extravagant that I considered it as not worth examining or even considering."[3] Despite Charpentier rejecting his theory, Perraudin eventually convinced Ignaz Venetz that it might be worth studying. Venetz convinced Charpentier, who in turn convinced the influential scientist Louis Agassiz that the glacial theory had merit.[2]

Agassiz developed a theory of what he termed "Ice Age" — when glaciers covered Europe and much of North America. In 1837 Agassiz was the first to scientifically propose that the Earth had been subject to a past ice age.[4] William Buckland had led attempts in Britain to adapt the geological theory of catastrophism to account for erratic boulders and other "diluvium" as relics of the Biblical flood. This was strongly opposed by Charles Lyell's version of Hutton's uniformitarianism, and was gradually abandoned by Buckland and other catastrophist geologists. A field trip to the Alps with Agassiz in October 1838 convinced Buckland that features in Britain had been caused by glaciation, and both he and Lyell strongly supported the ice age theory which became widely accepted by the 1870s.[1]

In the same general period that scientists first suspected climate change and ice ages, Joseph Fourier, in 1824, found that Earth's atmosphere kept the planet warmer than would be the case in a vacuum, and he made the first calculations of the warming effect. Fourier recognized that the atmosphere transmitted visible light waves efficiently to the earth's surface. The earth then absorbed visible light and emitted infrared radiation in response, but the atmosphere did not transmit infrared efficiently, which therefore increased surface temperatures. He also suspected that human activities could influence climate, although he focused primarily on land use changes. In a 1827 paper Fourier stated, "The establishment and progress of human societies, the action of natural forces, can notably change, and in vast regions, the state of the surface, the distribution of water and the great movements of the air. Such effects are able to make to vary, in the course of many centuries, the average degree of heat; because the analytic expressions contain coefficients relating to the state of the surface and which greatly influence the temperature."[5]

John Tyndall took Fourier's work one step further when he investigated the absorption of heat in different gases.[6]

First calculations of human-induced climate change, late 1800s

By the late 1890s, American scientist Samuel Pierpoint Langley had attempted to determine the surface temperature of the moon by measuring infrared radiation leaving the moon and reaching the earth.[7] The angle of the moon in the sky when a scientist took a measurement determined how much CO2 and water vapor the moon's radiation had to pass through to reach the earth's surface, resulting in weaker measurements when the moon was low in the sky. This result was unsurprising given that scientists had known about the greenhouse effect for decades.

Meanwhile, Swedish scientist Arvid Högbom had been attempting to quantify natural sources of emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) for purposes of understanding the global carbon cycle. Högbom decided to compare the natural sources with estimated carbon production from industrial sources in the 1890s.[8]

Another Swedish scientist, Svante Arrhenius, integrated Högbom and Langley's work. He realized that Högbom's calculation of human influence on carbon would eventually lead to a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide, and used Langley's observations of increased infrared absorption where moon rays pass through atmosphere at a low angle, encountering more CO2, to estimate an atmospheric warming effect from a future doubling of CO2. He also realized the effect would also reduce snow and ice cover on earth, making the planet darker and warmer. Adding in this effect gave a total calculated warming of 5-6 degrees Celsius. However, because of the relatively low rate of CO2 production in 1896, Arrhenius thought the warming would take thousands of years and might even be beneficial to humanity.[8]

Controversy and disinterest, early 1900s to mid 1900s

Arrhenius' calculations were disputed and subsumed into a larger debate over whether atmospheric changes had caused the ice ages. Experimental attempts to measure infrared absorption in the laboratory showed little differences resulted from increasing CO2 levels, and also found significant overlap between absorption by CO2 and absorption by water vapor, all of which suggested that increasing carbon dioxide emissions would have little climatic effect. These early experiments were later found to be insufficiently accurate, given the instrumentation of the time. Many scientists also thought that oceans would quickly absorb any excess carbon dioxide.[8]

While a few early 20th-Century scientists supported Arrhenius' work, including E. O. Hulburt and Guy Stewart Callendar, most scientific opinion disputed or ignored it through the early 1950s.[8]

Concern and increasing urgency, 1950s and 1960s

Better spectrography in the 1950s showed that CO2 and water vapor absorption lines did not overlap completely. Climatologists also realized that little water vapor was present in the upper atmosphere. Both developments showed that the CO2 greenhouse effect would not be overwhelmed by water vapor.[8]

Scientists began using computers to develop more sophisticated versions of Arrhenius' equations, and carbon-14 isotope analysis showed that CO2 released from fossil fuels were not immediately absorbed by the ocean. Better understanding of ocean chemistry led to a realization that the ocean surface layer had limited ability to absorb carbon dioxide. By the late 1950s, more scientists were arguing that carbon dioxide emissions could be a problem, with some projecting in 1959 that CO2 would rise 25% by the year 2000, with potentially "radical" effects on climate.[8]

By the 1960s, aerosol pollution ("smog") had become a serious local problem in many cities, and some scientists began to consider whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution could affect global temperatures. Scientists were unsure whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution or warming effect of greenhouse gas emissions would predominate, but regardless, began to suspect the net effect could be disruptive to climate in the matter of decades. In his 1968 book The Population Bomb, Paul R. Ehrlich wrote "the greenhouse effect is being enhanced now by the greatly increased level of carbon dioxide... [this] is being countered by low-level clouds generated by contrails, dust, and other contaminants... At the moment we cannot predict what the overall climatic results will be of our using the atmosphere as a garbage dump."[9]

Global cooling vs. global warming

Scientists in the 1970s started to shift from the uncertain leanings in the 1960s to increasingly a prediction of future warming. A survey of the scientific literature from 1965 to 1979 found 7 articles predicting cooling and 44 predicting warming, with the warming articles also being cited much more often in subsequent scientific literature.[10]

Several scientific panels from this time period concluded that more research was needed to determine whether warming or cooling was likely, indicating that the trend in the scientific literature had not yet become a consensus.[11][12] On the other hand, the 1979 World Climate Conference of the World Meteorological Organization concluded "it appears plausible that an increased amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can contribute to a gradual warming of the lower atmosphere, especially at higher latitudes....It is possible that some effects on a regional and global scale may be detectable before the end of this century and become significant before the middle of the next century."[13]

In July of 1979 the United States National Research Council published a report, [14] concluding (in part):

When it is assumed that the CO2 content of the atmosphere is doubled and statistical thermal equilibrium is achieved, the more realistic of the modeling efforts predict a global surface warming of between 2°C and 3.5°C, with greater increases at high latitudes. … … we have tried but have been unable to find any overlooked or underestimated physical effects that could reduce the currently estimated global warmings due to a doubling of atmospheric CO2 to negligible proportions or reverse them altogether. …

The mainstream news media at the time did not reflect scientific opinion. In 1975, Newsweek magazine published a story that warned of "ominous signs that the Earth's weather patterns have begun to change," and reported "a drop of half a degree [Fahrenheit] in average ground temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere between 1945 and 1968."[15] The article continued by stating that evidence of global cooling was so strong that meteorologists were having "a hard time keeping up with it."[15] On October 23, 2006, Newsweek issued an update stating that it had been "spectacularly wrong about the near-term future".[16]

Climate change scientific consensus begins development, 1980-1988

By the early 1980s, the slight cooling trend from 1945-1975 had stopped. Aerosol pollution had decreased in many areas due to environmental legislation and changes in fuel use, and it became clear that the cooling effect from aerosols was not going to increase substantially while carbon dioxide levels were progressively increasing.

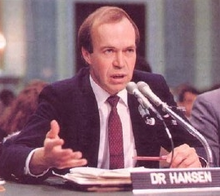

In 1985 a joint UNEP/WMO/ICSU Conference on the "Assessment of the Role of Carbon Dioxide and Other Greenhouse Gases in Climate Variations and Associated Impacts" assessed the role of carbon dioxide and aerosols in the atmosphere, and concluded that greenhouse gases "are expected" to cause significant warming in the next century and that some warming is inevitable.[17] In June 1988, James E. Hansen made one of the first assessments that human-caused warming had already measurably affected global climate.[18]

Modern period: 1988 to present

Both the UNEP and WMO had followed up on the 1985 Conference with additional meetings. In 1988 the WMO established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change with the support of the UNEP. The IPCC continues its work through the present day, and issues a series of Assessment Reports and supplemental reports that describe the state of scientific understanding at the time each report is prepared. Scientific developments during this period are discussed in the articles for each Assessment Report.

Discovery of other climate changing factors

Methane: In 1859, John Tyndall determined that coal gas, a mix of methane and other gases, strongly absorbed infrared radiation. Methane was subsequently detected in the atmosphere in 1948, and in the 1980s scientists realized that human emissions were having a substantial impact.[19]

Milankovitch cycles: Beginning in 1864, Scottish geologist James Croll theorized that changes in earth's orbit could trigger cycles of ice ages by changing the total amount of winter sunlight in the high latitudes. His theory was widely discussed but not accepted. Serbian geophysicist Milutin Milanković substantially revised the theory in 1941 with the publication of Kanon der Erdbestrahlung und seine Anwendung auf das Eiszeitenproblem (Canon of Insolation of the Earth and Its Application to the Problem of the Ice Ages). Milanković's ideas became the consensus position in the 1970s, when ocean sediment dating matched the prediction of 100,000 year ice-age cycles.

Chlorofluorocarbon: In 1973, British scientist James Lovelock speculated that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) could have a global warming effect. In 1975, Veerabhadran Ramanathan found that a CFC molecule could be 10,000 times more effective in absorbing infrared radiation than a carbon dioxide molecule, making CFCs potentially important despite the small amount in the atmosphere. While most early work on CFCs focused on their role in ozone depletion, by 1985, scientists had concluded that CFCs together with methane and other trace gases could have nearly as important a climate effect as increases in CO2.[19]

Published works discussing the history of climate change science

Historian Spencer Weart wrote The Discovery of Global Warming that summarized the history of climate change science, and provided an extensive supplementary website at the American Institute of Physics.[20]

The IPCC published a review of the later period of climate science in December 2004, "16 Years of Scientific Assessment in Support of the Climate Convention".[21]

The American Meteorological Society published "The Myth of the 1970s Global Cooling Consensus" that focuses on the middle period in climate science.[10]

The Long Thaw by David Archer is primarily about current understanding of climate science but also includes information about the science's history.[7]

Keeping Your Cool - Canada in a Warming World by Andrew Weaver addresses many questions about climate science including extensive discussion of its history.

See also

- Description of the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age in IPCC reports

- Historical climatology

- History of geology

- History of geophysics

References

- ^ a b Young, Davis A. (1995). The biblical Flood: a case study of the Church's response to extrabiblical evidence. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0719-4. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ a b Holli Riebeek (28 June 2005). "Paleoclimatology". NASA. Retrieved 01 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Imbrie, J. and K. P. Imbrie, 1979: Ice Ages, Enslow Publishers: Hillside, New Jersey.

- ^ E.P. Evans: The Authorship of the Glacial Theory, North American review. / Volume 145, Issue 368, July 1887. Accessed on February 25, 2008.

- ^ William Connolley. "Translation by W M Connolley of: Fourier 1827: MEMOIRE sur les temperatures du globe terrestre et des espaces planetaires". Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ John Tyndall (1872) "Contributions to molecular physics in the domain of radiant heat"DjVu

- ^ a b David Archer (2009). The Long Thaw: How Humans Are Changing the Next 100,000 Years of Earth's Climate. Princeton University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780691136547.

- ^ a b c d e f Spencer Weart (2003). "The Carbon Dioxide Greenhouse Effect". The Discovery of Global Warming.

- ^ Paul R. Ehrlich (1968). The Population Bomb. p. 52.

- ^ a b Peterson, T.C., W.M. Connolley, and J. Fleck (2008). "The Myth of the 1970s Global Cooling Scientific Consensus". Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 89: 1325–1337. doi:10.1175/2008BAMS2370.1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Science and the Challenges Ahead. Report of the National Science Board.

- ^ W M Connolley. "The 1975 US National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council Report". Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ "Declaration of the World Climate Conference" (PDF). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^

Report of an Ad Hoc Study Group on Carbon Dioxide and Climate, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, July 23-27, 1979, to the Climate Research Board, Assembly of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, National Research Council (1979). Carbon Dioxide and Climate:A Scientific Assessment. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. ISBN 0309119103.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Peter Gwynne (1975). "The Cooling World" (PDF).

- ^ Jerry Adler (23 October 2006). "Climate Change: Prediction Perils". Newsweek.

- ^ World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) (1986). "Report of the International Conference on the assessment of the role of carbon dioxide and of other greenhouse gases in climate variations and associated impacts". Villach, Austria. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ "Statement of Dr. James Hansen, Director, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies" (PDF). The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ a b Spencer Weart (2003). "Other Greenhouse Gases". The Discovery of Global Warming.

- ^ Spencer Weart (2003). "The Discovery of Global Warming". American Institute of Physics.

- ^ "16 Years of Scientific Assessment in Support of the Climate Convention" (PDF). 2004. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

External links

- Joseph Fourier's 1827 article, Memoire sur les temperatures du globe terrestre et des espaces planetaires, in French and English, with annotations by William Connolley

- Svante Arrhenius' April 1896 article, On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground

- How Was the Greenhouse Effect Discovered?