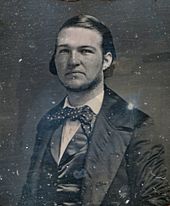

Horace Gray

Horace Gray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office December 20, 1881 – September 15, 1902 | |

| Nominated by | Chester Arthur |

| Preceded by | Nathan Clifford |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Holmes |

| Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | |

| In office September 5, 1873 – January 9, 1882 | |

| Nominated by | William Washburn |

| Preceded by | Reuben Chapman |

| Succeeded by | Marcus Morton |

| Associate Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | |

| In office August 23, 1864 – September 5, 1873 | |

| Nominated by | John Andrew |

| Preceded by | Pliny Merrick |

| Succeeded by | Charles Devens |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 24, 1828 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 15, 1902 (aged 74) Nahant, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

Horace Gray (March 24, 1828 – September 15, 1902) was an American jurist who ultimately served on the United States Supreme Court. He was active in public service and a great philanthropist to the City of Boston.

Early life

Gray was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to the prominent Boston Brahmin merchant family of William Gray. He enrolled at Harvard College at the age of 13, graduated four years later and traveled in Europe for a time before returning home following a series of business problems for his family. He studied law at Harvard, although he did not receive a degree. Gray entered the bar in 1851. Gray's home later became the site of the Third Church of Christ, Scientist (Washington, D.C.)

Horace Gray's half-brother, John Chipman Gray went on to become a lawyer and long-time professor at Harvard Law School.

Judicial career

In 1854, he was named Reporter of Decisions for the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, a very prestigious appointment for so young a man and one which allowed him to edit numerous volumes of court records and provided for some independent legal writing, all of which earned him a very good reputation as a scholar and legal historian. This reputation made him a natural choice when a vacancy opened up on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in 1864. At age 36, Gray was youngest appointee in that court's history. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1860,[1] and in 1866, was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[2]

Gray maintained a good reputation on the state supreme court, and became the court's Chief Justice in 1873. While serving as chief justice, Gray hired Louis D. Brandeis as a clerk, becoming the first justice of that court to hire a clerk.[3]

Supreme Court

On 1881, President Chester A. Arthur nominated Gray to a vacancy on the Supreme Court of the United States; he was confirmed the following day, replacing Nathan Clifford. In 1889, Gray married Jane Matthews, who was the daughter of his former colleague on the court, Thomas Stanley Matthews. As he had been in Massachusetts, Gray was the first Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court to hire a law clerk. He used his own funds to pay the clerk's salary, as no government money was appropriated for this purpose at the time.

Gray served on the US Supreme Court for over 20 years, resigning in July, 1902, gravely ill. He was succeeded by a fellow Massachusetts native, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who, like Gray, previously served on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

Gray was one of the few Supreme Court appointees in the latter half of the 19th century who had not previously been a politician, and he maintained the opinion that law and politics were entirely separate fields. His opinions, both concurring and dissenting, were generally very long and weighted with legal history.

Gray is well known for his decision in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. This case was heard twice, though only the second hearing resulted in a decision; the justices, feeling that the opinions written had not adequately explained their view of the situation (the case was about the constitutionality of a national income tax), wished to rehear the case. After the first hearing, Gray wrote that he sided with the defendant (Farmer's Loan & Trust), arguing that the tax was indeed constitutional. He was in the minority, however. After the second hearing, Gray changed his stance, joining with the majority in favor of the plaintiff. He chose not to write a dissenting or concurring opinion, in either hearing.

Probably the most famous of Justice Gray's opinions is Mut. Life Ins. Co. of N.Y. v. Hillmon (1892), which held that a declarant's out-of-court statement of his intention to do something or go somewhere in the future is admissible under the "state-of-mind" hearsay exception. "The letters in question were competent, not as narratives of facts communicated to [Walters] by others, nor yet as proof that he actually went away from Wichita, but as evidence that, shortly before the time when other evidence tended to show that he went away, he had the intention of going, and of going with Hillmon, which made it more probable both that he did go and that he went with Hillmon, than if there had been no proof of such intention." This holding gained wide acceptance and is now codfied in Rule 803(3) of the Federal Rules of Evidence, as well as the evidence law in most states.

Horace Gray was also the author of the 1898 case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, ruling that "a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicil and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States." 169 U.S. 649;705.

Horace Gray sided with the majority in the infamous case Plessy v. Ferguson that upheld racial segregation.

See also

- Samuel Williston who worked as Justice Gray's private secretary

References

- ^ American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter G" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Peppers, Todd C. (2006). Courtiers of the Marble Palace: The Rise and Influence of the Supreme Court Law Clerk. Stanford University Press. pp. 44–5.

- Data drawn in part from the Supreme Court Historical Society and Oyez.

Further reading

- Spector, Robert M. (1968). "Legal Historian on the United States Supreme Court: Justice Horace Gray, Jr., and the Historical Method". American Journal of Legal History. 12 (3). Temple University: 181–210. doi:10.2307/844125. JSTOR 844125.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Koslosky, Daniel Ryan, "Ghosts of Horace Gray: Customary International Law as Expectation in Human Rights Litigation" 97 Kentucky Law Journal 615 (2009)

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1882–1887 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1888 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1888–1889 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1890–1891 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1891–1892 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1892–1893 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1893 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1894–1895 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1896–1897 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1898–1902 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- 1828 births

- 1902 deaths

- 19th-century American judges

- 20th-century American judges

- American legal writers

- American Unitarians

- Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery

- Chief Justices of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Lawyers from Boston

- Massachusetts Republicans

- United States federal judges appointed by Chester A. Arthur

- United States Supreme Court justices

- Members of the American Antiquarian Society