Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin

The Indigenous Peoples of the Great Basin are Native Americans of the northern Great Basin, Snake River Plain, and upper Colorado River basin. The "Great Basin" is a cultural classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas and a cultural region located between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada, in what is now Nevada, and parts of Oregon, California, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah. There is very little precipitation in the Great Basin area which affects the lifestyles and cultures of the inhabitants.

History

Original inhabitants of the region may have arrived by 12,000 BCE. 9,000 BCE to 400 CE marks the Great Basin Desert Archaic Period, following by the time of the Fremont culture, who were hunter-gatherers, as well as agriculturalists. Numic language-speakers, ancestors of today's Western Shoshone and both Northern and Southern Paiute peoples entered the region around the 14th century CE.[2]

The first Europeans to reach the area was the Spanish Dominguez-Escalante Expedition, who passed far from present day Delta, Utah in 1776.[2] Great Basin settlement was relatively free of non-Native settlers until the first Mormon settlers arrived in 1847. Within ten years, the first Indian reservation was established, in order to assimilate the native population. The Goshute Reservation was created in 1863.[2] The attempted acculturation process included sending children to Indian schools and limiting the landbases and resources of the reservations.

Because their contact with European-Americans and African-Americans occurred comparatively late, Great Basin tribes maintain their religion and culture and were leading proponents of 19th century cultural and religious renewals. Two Paiute prophets, Wodziwob and Wovoka, introduced the Ghost Dance in a ceremony to commune with departed loved ones and bring renewal of buffalo herds and precontact lifeways. The Ute Bear Dance emerged on the Great Basin. The Sun Dance and Peyote religion flourished in the Great Basin, as well.[3]

In 1930, the Ely Shoshone Reservation was established, followed by the Duckwater Indian Reservation in 1940.[2]

Conditions for the Native American population of the Great Basin were erratic throughout the 20th century. Economic improvement emerged as a result of President Franklin Roosevelt's Indian New Deal in the 1930s, while activism and legal victories in the 1970s have improved conditions significantly. Nevertheless, the communities continue to struggle against chronic poverty and all of the resulting problems: unemployment; substance abuse; and high suicide rates.

Today self-determination, beginning with the 1975 passage of the Indian Self-determination and Education Assistance Act,[2] has enabled Great Basin tribes to develop economic opportunities for their members.

Cultures

Different ethnic groups of Great Basin tribes share certain common cultural elements that distinguish them from surrounding groups. All but the Washoe traditionally speak Numic languages, and tribal groups, who historically lived peacefully and often shared common territories, have intermingled considerably. Prior to the 20th century, Great Basin peoples were predominantly hunters and gatherers.

"Desert Archaic" or more simply "The Desert Culture" refers to the culture of the Great Basin tribes. This culture is characterized by the need for mobility to take advantage of seasonally available food supplies. The use of pottery was rare due to its weight, but intricate baskets were woven for containing water, cooking food, winnowing grass seeds and storage—including the storage of pine nuts, a Paiute-Shoshone staple. Heavy items such as metates would be cached rather than carried from foraging area to foraging area. Agriculture was not practiced within the Great Basin itself, although it was practiced in adjacent areas (modern agriculture in the Great Basin requires either large mountain reservoirs or deep artesian wells). Likewise, the Great Basin tribes had no permanent settlements, although winter villages might be revisited winter after winter by the same group of families. In the summer, the largest group was usually the nuclear family due to the low density of food supplies.

In the early historical period the Great Basin tribes were actively expanding to the north and east, where they developed a horse-riding bison-hunting culture. These people, including the Bannock and Eastern Shoshone share traits with Plains Indians.

Great Basin peoples

- Bannock, Idaho[4]

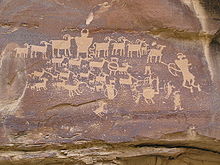

- Coso People, of Coso Rock Art District in the Coso Range, Mojave Desert California

- Fremont culture (400 CE–1300 CE), Utah[3]: 161

- Kawaiisu, southern inland California[4]

- Mono, southeastern California

- Eastern Mono (Owens Valley Paiute), southeastern California

- Western Mono, southeastern California

- Timbisha or Panamint or Koso, southeastern California

- Washo, Nevada and California[5]

Paiute

- Northern Paiute, eastern California, Nevada, Oregon, southwestern Idaho[4]

- Kucadikadi, Mono Lake Paiute, California

- Owens Valley Paiute, California Nevada

- Southern Paiute, Arizona, Nevada, Utah[6]

- Chemehuevi, southeastern California

- Kaibab, northwestern Arizona

- Kaiparowtis, southwestern Utah

- Moapa, southern Nevada

- Panaca

- Panguitch, Utah

- Paranigets, southern Nevada

- Shivwits, southwestern Utah

Shoshone

- Guchundeka', Kuccuntikka, Buffalo Eaters[7][8]

- Tukkutikka, Tukudeka, Mountain Sheep Eaters, joined the Northern Shoshone[8]

- Boho'inee', Pohoini, Pohogwe, Sage Grass people, Sagebrush Butte People[7][8][9]

- Agaideka, Salmon Eaters, Lemhi, Snake River and Lemhi River Valley[9][9][10]

- Doyahinee', Mountain people[7]

- Kammedeka, Kammitikka, Jack Rabbit Eaters, Snake River, Great Salt Lake[9]

- Hukundüka, Porcupine Grass Seed Eaters, Wild Wheat Eaters, possibly synonymous with Kammitikka[9][11]

- Tukudeka, Dukundeka', Sheep Eaters (Mountain Sheep Eaters), Sawtooth Range, Idaho[9][10]

- Yahandeka, Yakandika, Groundhog Eaters, lower Boise, Payette, and Wiser Rivers[9][10]

-

- Kuyatikka, Kuyudikka, Bitterroot Eaters, Halleck, Mary's River, Clover Valley, Smith Creek Valley, Nevada[11]

- Mahaguadüka, Mentzelia Seed Eaters, Ruby Valley, Nevada[11]

- Painkwitikka, Penkwitikka, Fish Eaters, Cache Valley, Idaho and Utah[11]

- Pasiatikka, Redtop Grass Eaters, Deep Creek Gosiute, Deep Creek Valley, Antelope Valley[11]

- Tipatikka, Pinenut Eaters, northernmost band[11]

- Tsaiduka, Tule Eaters, Railroad Valley, Nevada[11]

- Tsogwiyuyugi, Elko, Nevada[11]

- Waitikka, Ricegrass Eaters, Ione Valley, Nevada[11]

- Watatikka, Ryegrass Seed Eaters, Ruby Valley, Nevada[11]

- Wiyimpihtikka, Buffalo Berry Eaters[11]

Ute

- Capote, southeastern Colorado and New Mexico[3]: 339

- Moanunts, Salina, Utah

- Muache, south and central Colorado[3]: 282

- Pahvant, western Utah

- Sanpits, central Utah

- Timpanogots, north central Utah

- Uintah, Utah

- Uncompahgre or Taviwach, central and northern Colorado

- Weeminuche, western Colorado, eastern Utah, northwestern New Mexico

- White River Utes (Parusanuch and Yampa), Colorado and eastern Utah

Notes

- ^ Pritzker, Barry M (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples (Google Books). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ a b c d e "History Timeline of Great Basin National Heritage Area." Great Basin National Heritage Area. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d D'Azevedo, Warren L (editor) (1986). Volume 11: Great Basin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-16-004581-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c D'Azevedo ix

- ^ Nicholas, Walter S. "A Short History of Johnsondale". RRanch.org. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ Pritzker 230

- ^ a b c Loether, Christopher. "Shoshones." Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Retrieved 20 Oct 2013.

- ^ a b c Shimkin 335

- ^ a b c d e f g Murphy and Murphy 306

- ^ a b c Murphy and Murphy 287

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Thomas, Pendleton, and Cappannari 280–283

External links

- Great Basin Native Artists, a collective of indigenous artists from the Great Basin

- Great Basin artwork in Infinity of Nations, National Museum of the American Indian

- Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin

- History of the Great Basin

- Indigenous peoples of North America

- Native American tribes

- Native American tribes in California

- Native American tribes in Idaho

- Native American tribes in Nevada

- Native American tribes in Oregon

- Native American tribes in Utah

- Native American tribes in Wyoming

- Great Basin

- Western United States