John K. Kane

John K. Kane | |

|---|---|

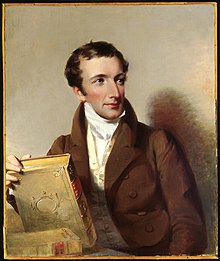

Portrait, 1824, by Thomas Sully | |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania | |

| In office June 17, 1846 – February 21, 1858 | |

| Appointed by | James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | Archibald Randall |

| Succeeded by | John Cadwalader |

| 21st Attorney General of Pennsylvania | |

| In office January 21, 1845 – June 17, 1846 | |

| Preceded by | Ovid F. Johnson |

| Succeeded by | John M. Read |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 16, 1795 Albany, New York |

| Died | February 21, 1858 (aged 62) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Spouse | Jane Duval Leiper |

| Relations | Robert Van Rensselaer (grandfather) |

| Children | 7, including Elisha, Thomas |

| Parent(s) | Elisha Kane Alida Van Rensselaer |

| Alma mater | Yale College |

| Profession | Attorney, Judge |

John Kintzing Kane (May 16, 1795 – February 21, 1858) was an American politician, attorney and jurist. Kane was noted for his political affiliation with President Andrew Jackson and for an 1855 pro-slavery legal decision related to the freeing of Jane Johnson and application of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

Early life

Kane was born in Albany, New York in 1795, the son of Elisha Kane and Alida (née Van Rensselaer), daughter of Brigadier General Robert Van Rensselaer and Cornelia Rutsen. When his mother Alida died in 1799, Elisha married Elizabeth Kintzing, and it was she who raised John and his siblings.[1]

He graduated from Yale College in 1814, studied law with Joseph Hopkinson, and was admitted to the bar on April 18, 1817. He established a legal practice in Philadelphia.

Career

Intensely interested in politics and public affairs, Kane was a member of the Federalist party as a young man and served in the Pennsylvania legislature in 1823. Shortly afterward, he moved his allegiance to the Democratic party. He filled the office of solicitor of Philadelphia in 1828-1830.

Kane supported Andrew Jackson in 1828, and received a number of appointments and honors during Jackson's administration. In 1832, Kane was appointed as one of three commissioners under the "Convention of Indemnity with France of 4 July of 1831." This commission was charged with collecting reparations paid by France to the United States for damages the country had received to its shipping and trade during recent European wars. He was a primary author of the commission's report, and prepared the record of "Notes" on questions decided by the board. This material was published after the conclusion of the board's activities in 1836.

Kane drafted the first printed attack on the United States Bank, and is credited with preparing written materials and speeches on the topic which were used by President Jackson. His friendship with the President led to a period of social difficulty in Philadelphia, which was a stronghold of the "bank" party. A memorable letter addressed by Jackson to James K. Polk during the campaign of 1844 was written by Kane, and he was an effective manager of the Democratic party during what is known as the Buckshot War in Pennsylvania.

Legal positions and rulings

Kane served as city solicitor for Philadelphia 1828-1830 and in 1831. He was appointed as attorney-general of Pennsylvania in 1845. On June 11, 1846, Kane was nominated by President James K. Polk to a seat as a United States District Court judge for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, which had been vacated by Archibald Randall. Kane was confirmed by the United States Senate on June 17, 1846, and received commission the same day. He held that judicial office for the rest of his life. He was distinguished both for his knowledge of the law and his judicial decisions. Many of his rulings affected admiralty and patent law.

In 1855 he heard the charges against abolitionists Passmore Williamson and William Still, both with the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and its Vigilance Committee, and five black men who were dockworkers, accused of forcible abduction and riot in the freeing of the slave Jane Johnson, who was owned by John Hill Wheeler, newly appointed US Minister to Nicaragua. Kane sentenced Williamson to three months in prison for contempt of court under the Fugitive Slave Law, for failing to tell where Johnson was being held (Williamson had not been told, so truthfully could say he did not know).

In this case, which was tried a year and a half earlier than the better-known Dred Scott decision, Kane ruled that the fugitive slave had no legal rights and rejected her testimony as immaterial. He placed legal penalties on the actions of abolitionists. Johnson and her sons evaded capture, and were moved via the Underground Railroad to Boston, where they lived free the rest of their lives. Her son Isaiah Johnson fought with the United States Colored Troops during the American Civil War.

Kane was violently attacked for his ruling by the Abolition party and the liberal press. Angry stories were found in major papers, including Horace Greeley's influential New York Tribune, the National Anti-Slavery Standard of New York, and William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator of Boston. The Hartford Religious Herald wrote:

A tyrannical judge is one of the vilest and most dangerous of despots. We refer to Judge Kane of Philadelphia. Fellow citizens of the North, let us unite to free our country from this degrading bondage of the Slave Power.

The Judge's son, Thomas L. Kane, held a position as a Clerk of the District Court in eastern Pennsylvania. An abolitionist, Thomas Kane was distressed at the passage of the Compromise of 1850 and the associated Fugitive Slave Act, which increased the legal responsibilities of officials even in free states to cooperate in the capture and return of fugitive slaves to Southern owners. He tendered his resignation to his father, who had the younger Kane jailed for contempt of court. The U.S. Supreme Court overruled this arrest.

Although the public breach between father and son was well known, Thomas and his wife Elizabeth D.W. Kane continued to live at the home of his father. The Judge politely ignored the unidentified negroes whom Thomas brought to their home, only to take them to other stations on the Underground Railroad later in the night. Although Judge Kane believed he had to enforce Federal slavery laws in court, he colluded with the anti-slavery acts of his son.

Other work

Kane was active in founding Girard College and was involved in the appointment of the institution's first board of trustees. Kane was one of the trustees and legal advisers of the Presbyterian church in the United States. He also took a prominent role in the controversy which eventually divided the Presbyterian church into the "new" and "old" schools. From 1856 until his death, he was President of the American Philosophical Society.

Personal life

In 1819, Kane was married to Jane Duval Leiper (1796–1866), the daughter of Thomas Leiper (1745–1825). Together, they had seven children, including one that died in infancy.[2] Two sons became well known as adults:

- Elisha Kent Kane (1820–1857), who was a United States naval officer, physician and explorer. He was a member of two Arctic expeditions that tried to rescue the explorer Sir John Franklin and his team

- Thomas Leiper Kane (1822–1883), who was an attorney, abolitionist and military officer, who was influential in the western migration of the Latter-day Saints movement and served as a Union colonel and general of volunteers in the American Civil War.

- Elizabeth Kane (1830–1869), who married Charles Woodruff Shields (1825–1904) in 1861.

Kane died in Philadelphia on February 21, 1858, and was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

References

- ^ Reynolds, Cuyler (1914). Genealogical and Family History of Southern New York and the Hudson River Valley: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Building of a Nation. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. p. 1151. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Matthew J. Grow (2009). Liberty to the Downtrodden: Thomas L. Kane, Romantic Reformer. Yale University Press. p. 4.

Further reading

- Kevin R. Chaney. "Kane, John Kintzing"; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000. Accessed October 2006 (subscription required).

- King, Moses. Philadelphia and Notable Philadelphians. New York: 1901.

- John Kintzing Kane at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Biographical and genealogical history of the state of Delaware (Volume 2) Brief bio of son Dr John Kintzing Kane

- Matthew J. Grow (2009). Liberty to the Downtrodden: Thomas L. Kane, Romantic Reformer. Yale University Press.

External links

- 1795 births

- 1858 deaths

- Judges of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

- United States federal judges appointed by James K. Polk

- 19th-century American judges

- Members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives

- Pennsylvania Federalists

- Pennsylvania Democrats

- Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia)

- 19th-century American politicians

- Politicians from Albany, New York

- United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law

- Lawyers from Albany, New York

- American proslavery activists