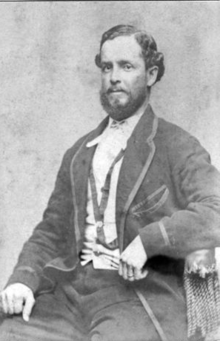

Thomas Cardozo

Thomas Cardozo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mississippi Superintendent of Public Instruction | |

| In office 1874–1876 | |

| Governor | Adelbert Ames |

| Preceded by | Henry R. Pease |

| Succeeded by | Thomas S. Gathright |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 19, 1838 Charleston, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | April 13, 1881 (aged 42) Newton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Laura J. Williams |

| Relatives | Henry Weston Cardozo (brother) Francis Lewis Cardozo (brother) Benjamin N. Cardozo (distant relative) |

| Profession |

|

Thomas Whitmarsh Cardozo (December 19, 1838[1] – April 13, 1881[2]) was an American educator, journalist, writer, and public official during the Reconstruction Era in the United States.[1][3] He adopted the name Civis as a nom de plume and wrote as a correspondent for the New National Era, founded by Frederick Douglass. He was the first African American to hold the position of State Superintendent of Education in Mississippi.[4]

Early life

[edit]Thomas Whitmarsh Cardozo was born in 1838 in Charleston, South Carolina, as the youngest of five children. His father, Isaac Nunez Cardozo, was part of a well-known Sephardic Jewish family[5] and was a weigher in the U.S. Customs House of Charleston for 24 years, until his death in 1855.[6] Thomas's mother was Lydia Weston,[note 1] a freed slave[note 2] of mixed ancestry who was a seamstress. He had two older brothers, Henry Weston Cardozo and Francis Lewis Cardozo, and two older sisters, Lydia Frances Cardozo and Eslander Cardozo.[1][9][10][note 3]

In Charleston, Thomas was among the "free-Negro elite" and went to private schools for free black children, mainly taught by free black teachers.[12][13] He was also taught by his father Isaac and his uncle Jacob Cardozo,[13] who was an economist and newspaper publisher.[14]

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the secession movement caused free people of color to be concerned about being enslaved.[11] When Isaac Cardozo died during this worsening time, Thomas's family lost their protector. Thomas was 17 at the time and became an apprentice in a company that manufactured rice-threshing machines,[12][15] working with his eldest brother Henry.[citation needed]

In 1857, two years after his father's death, Thomas moved to New York where he continued his education. In June 1858, his mother, sisters, and brother Henry left Charleston on the steamship Nashville for New York;[16] by 1860 they had settled in Cleveland, Ohio.[17] His brother Francis was in school at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. At the Newburgh Collegiate Institute, a private boys school, Thomas took academic courses and trained to be a teacher. Before he could graduate, the Civil War broke out and he began teaching in 1861.[12][15] He married Laura J. Williams, a teacher and accomplished musician who was from a mixed-race family in Brooklyn. Thomas and Laura became parents with a son, Alvin, born in 1863, and another son, Francis, in 1865.[18]

Career in education

[edit]Shortly after the beginning of the American Civil War, Cardozo began teaching in New York. A few years later in April 1865 at the end of the war, Thomas and his family moved from Flushing, New York, to his home town of Charleston, South Carolina.[12]

In Charleston, in the challenging turmoil of the weeks following the end of the Civil War, he supervised the educational activities of the American Missionary Association (AMA). He obtained building space and books. He supervised teachers, hired new teachers, and ran the AMA house for teachers who came down from the north. All this was in the context of disputes between the various aid agencies there.[12] Cardozo was the first AMA school principal in Charleston at the Tappan School.[19]

A few months after he began work in Charleston, the AMA became aware of a previous affair that the married Thomas Cardozo had with a female student of his in New York. Also, the AMA was dissatisfied with his accounting of his expenditures back then and suspected that some of the expenditures went to the young woman. The AMA asked his brother Francis Cardozo to discuss this with him in Charleston. Francis reported back that Thomas had the affair through "weakness", had “not been deliberately wicked”, and didn't misappropriate any AMA funds. Thomas asked for forgiveness. In response, the AMA replaced Thomas with Francis around September 1865.[20][21]

Thomas stayed in Charleston and became a grocer for a few months until his store burnt down. He moved to Baltimore, Maryland where he and his wife taught at the Negro Industrial School for a short time. When the school lost its funding in 1866, he and his family moved to Syracuse, New York. There, with the help of Samuel Joseph May, he raised funds for teaching in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, in a program of the New York Freedmen's Union Commission.[22]

In the spring of 1869, the Cardozos moved to Elizabeth City, where Thomas and his wife taught for about four months until the program ended. They went back to the North to try to find support for their educational work in North Carolina. Cardozo brought with him a letter of commendation from North Carolina U. S. Senator John Pool that was endorsed by North Carolina Governor William Woods Holden and other state officials. After Cardozo gained the support of a branch of the Freedmen's Union Commission, he obtained a thousand dollars from the Freedmen's Bureau for construction of a normal school in Elizabeth City to train high school graduates to be teachers. It opened in the fall of 1870 with 123 students.[22][23]

In January 1871, Thomas Cardozo and his family moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where he and his wife immediately began teaching.[24] Several years later he served as State Superintendent of Education from 1874 to 1876.[25][26] Cardozo proposed uniform textbooks for Mississippi schools during his tenure.[25][27]

Career in politics

[edit]"Whenever I sit to sketch the various members of the Legislature it kindles within me a warm feeling for the many good qualities and earnest friendship of all of them."

— Civis (Thomas Cardozo), March 24, 1873[28]

In New York, Cardozo had written in 1868 and 1869 in the National Anti-Slavery Standard about the place for blacks in the evolving political situation of reconstruction.[29] As a republican, Cardozo ran for Sheriff of Pasquotank County, North Carolina, and lost on August 4, 1870.[30] Five months later he moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, in January 1871.[24][31]

Since the large majority of voters in Mississippi were black with too few educated enough to provide political leadership, public office for Cardozo was a good possibility after satisfying the six-month residency requirement in July 1871.[32] He joined the Republican Party,[33] was elected circuit court clerk of Warren County and took office on January 1, 1872.[34] He wrote accounts of his experiences in Mississippi, including descriptions of his fellow Republican politicians, for the New National Era under the pseudonym "Civis".[33][note 4] He was a delegate to the 1873 National Civil Rights Convention in Washington, D.C.[35]

In November 1873, Cardozo was elected State Superintendent of Education in Mississippi, along with the election of Governor Adelbert Ames, Lieutenant Governor Alexander K. Davis and Secretary of State James Hill.[36][37] Although he was the first African-American to hold the post, Cardozo did not challenge the de facto racial segregation that existed in Mississippi schools.[25][note 5]

In August 1874, conservative whites took over the Vicksburg city government and Cardozo was charged with crimes while he was circuit court clerk in 1872. First he was charged with receiving money for falsified witness certificates and then additionally charged with embezzling money paid by land owners for redeeming land taken by the government for unpaid taxes. He appeared before a magistrate on September 7, 1874 and bond was posted. He was indicted in November 1874 and tried beginning May 6, 1875. The jury failed to reach a verdict. He was able to get the retrial moved from Vicksburg to Jackson with a new trial date in July 1876.[39]

After the first trial, the ongoing political attacks by conservative whites against Republican office holders turned into violence. On July 4, 1875 in Vicksburg, a white mob attacked a meeting where Cardozo was to speak, followed by street violence where several blacks were killed or injured. City officials helped Cardozo, the main target of the attacks, escape from the city.[40]

The occupying Army began to withdraw from the South in 1875 in the last years of the Reconstruction era. White Democrats had regained control of the Mississippi state legislature by a program of violence and intimidation against Republican black voters, known as the Mississippi Plan. The legislators brought impeachment charges against Superintendent Cardozo and the Senate impeachment trial began February 11, 1876.[note 6] The most incriminating charge was that he embezzled money from Tougaloo University.[41] Cardozo was granted permission to resign with the charges against him dismissed, and submitted his resignation on March 22, 1876.[42][43][note 7]

Later years

[edit]Leaving the politics, an upcoming trial in Jackson in July 1876, and the dangerous situation in Mississippi, Cardozo moved to Newton, Massachusetts. There he worked for the postal service until his death from disease[note 8] in 1881. He was forty-two.[42] Thomas Cardozo Middle School in Jackson, Mississippi, of the Jackson Public School District, is named for him and opened in September 2010.[4][45]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Although some authors refer to Thomas Cardozo's mother as Lydia Williams, official records for 1855 and 1857 indicate that her name was Lydia Weston. Her deceased former owner was Plowden Weston.[7]

- ^ The will of her deceased former owner, Plowden Weston, effectively freed her in 1826, but didn't legally free her.[8]

- ^ It's unclear whether there were other siblings. For example, one source said there was also a sister Lydia and a brother Jacob.[11]

- ^ See Further reading for some of Civis's writings.

- ^ Using the pseudonym Civis in the New National Era, Cardozo advocated for a school desegregation clause to be in the federal Civil-Rights Bill.[38]

- ^ See Further reading for State Senate impeachment proceedings.

- ^ According to his biographer, Euline W. Brock, "Yearning for wealth and status, Cardozo capitalized on party weaknesses and eventually brought opprobrium on himself and his party."[44]

- ^ The disease was listed as albumenia in 1881 Massachusetts records, which corresponds to the modern term albuminuria. See Reference desk, February 8, 2021.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Brock, Euline W. (1981). "Thomas W. Cardozo: Fallible Black Reconstruction Leader" (PDF). The Journal of Southern History. 47 (2): 183–206. doi:10.2307/2207949. JSTOR 2207949. (p. 186)

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 204, footnote 89

- ^ Richter, William L. (December 1, 2011). Historical Dictionary of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810879591 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Cardozo Middle School — About Cardozo". Jackson Public Schools. August 8, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Waldfogel, Sabra (August 1, 2014). "Jews and Slavery: Isaac Cardozo and Lydia Weston". Jewish Book Council. Retrieved Jan 4, 2021.

- ^ Fick, Sarah; et al. "Cardozo Family — A family whose descendants shaped history". Mapping Jewish Charleston. College of Charleston. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Kinghan, Neil (2019). A Brief Moment in the Sun: Francis Cardozo and Reconstruction in South Carolina (PDF) (PhD). University College London. pp. 65–67

- ^ Kinghan 2019, pp. 61–62, 66–67

- ^ 1850 Census, Charleston, South Carolina, St. Michael and St. Philip, Line Number 15 Dwelling Number 167

- ^ Kinghan 2019, pp. 67–68

- ^ a b Waldfogel, Sabrah (August 1, 2014). "Jews and Slavery: Isaac Cardozo and Lydia Weston". Jewish Book Council. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Brock 1981, p. 188

- ^ a b Kinghan 2019, p. 69

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 186, footnote 10

- ^ a b "Hon. T. W. Cardozo". New National Era and Citizen. Vol. 4, no. 37. September 18, 1873. p. 3. (Image 3) Column 1. Reprinted from Jackson Mississippi Pilot.

- ^ The Charleston Daily Courier, 28 Jun 1858, Page 4

- ^ 1860 Census, Cleveland Ohio, Ward 4, Dwelling Number 1028, Family Number 1039

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 188, main text and footnote 15.

- ^ Kinghan 2019, p. 114

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 189

- ^ Kinghan 2019, p. 115

- ^ a b Brock 1981, pp. 189–190

- ^ Ballou, Leonard B. (1987). "Thomas W. Cardozo Unsung Schoolmaster and Politician" (PDF). Elizabeth City State University.

- ^ a b Brock 1981, p. 191

- ^ a b c Brock 1981, p. 197

- ^ Biennial Reports of the Departments and Benevolent Institutions, of the State Of Mississippi for the Years 1896–97 (Report). 1898. p. 95. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "Cardozo Middle School". Jackson Public Schools. August 17, 2016.

- ^ Civis (April 3, 1873). "Personnel of the Mississippi Legislature". New National Era. Vol. IV, no. 13. Washington, D.C.

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 190

- ^ Ballou, Leonard B. (1966). "Chapter 1: Cardozo — Schoolmaster and Politician". Pasquotank Pedagogoues and Politicians: Early Educational Struggles (PDF). Elizabeth City, North Carolina: Elizabeth City State College. p. 7

- ^ Ballou 1966, p. 10

- ^ Brock 1981, pp. 191–192

- ^ a b Brock 1981, p. 192

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 193

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 195

- ^ W.E.B. Du Bois (1935). "XI. The Black Proletariat in Mississippi and Louisiana". Black Reconstruction in America (1860-1880). Meridian. p. 444–5.

- ^ Biennial Reports of the Departments and Benevolent Institutions, of the State Of Mississippi for the Years 1896–97 (Report). 1898. p. 95. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ New National Era July 2, 1874.

- ^ Brock 1981, pp. 198–201

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 201

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 203

- ^ a b Brock 1981, p. 204

- ^ Resignation letters can be viewed at: "Cardozo, Thomas Whitmarsh". cwrgm.org. The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Brock 1981, p. 185

- ^ Mississippi Legislature 2009 Regular Session, House Resolution 14 — "A Resolution Congratulating the Family of Superintendent Thomas W. Cardozo, on the Dedication of a Middle School Named in His Honor by the Jackson Public Schools." January 16, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- "Impeachment Trial of Thomas W. Cardozo, State Superintendent of Public Education". Journal of the Senate of the State of Mississippi: Sitting as a Court of Impeachment, in the Trials of Adelbert Ames, Governor, Alexander K. Davis, Lieutenant Governor, Thomas W. Cardozo, Superintendent of Public Education.: 1–59. 1876. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Writings in the New National Era

- – by Thomas Cardozo under the pseudonym Civis,

- – by Cardozo under his own name — Aug 3, 1871

- – by others about Cardozo/Civis — R. W. Fluornoy, Oct 12, 1871;[a] Student, May 2, 1872;[b] Dufoy, Jan 16, 1873;[c] May 8, 1873;[d] H. C. Carter, Nov 20, 1873;[e] Robert C. MacGregor, Jul 16, 1874 [f]

- – a reprint from the Mississippi Pilot about Cardozo — Sep 18, 1873

- ^ Fluornoy criticized Civis's comments from the Sep 14, 1871 issue.

- ^ Student criticized Civis's comments from the Apr 4, 1872 issue.

- ^ Dufoy discussed some of Civis's comments from the Dec 26, 1872 issue.

- ^ New National Era's rejection of a letter critical of Civis that "...attacks, without assigning sufficient reasons, a gentleman whose letters have received wide commendation."

- ^ Carter criticized Civis's comments from the Oct 30, 1873 issue. Civis responded in the Dec 11, 1873 issue.

- ^ MacGregor criticized Civis's comments from the Jul 2, 1874 issue, asked if Civis was T. W. Cardoza [sic], and said he should respond to various accusations from the press. Civis didn't write any more for the New National Era after this. (Thomas W. Cardozo: Fallible Black Reconstruction Leader See p. 198: main text and footnote 62.)

- 1838 births

- 1881 deaths

- African-American politicians during the Reconstruction Era

- American people of Jewish descent

- Politicians from Charleston, South Carolina

- 19th-century American educators

- 19th-century African-American educators

- United States officials impeached by state or territorial governments

- Mississippi State Superintendent of Education