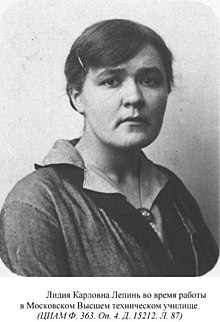

Lidija Liepiņa

Lidija Liepina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 4 April 1891 |

| Died | 4 September 1985 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | Latvian |

| Other names | Lydia Lepin[1] |

| Known for | helped test and improve the first Russian gas mask |

| Awards | Hero of Socialist Labour |

Lidija Liepiņa (Latvian pronunciation: [ˈli.di.ja ˈli͡ɛ.pi.ɲa], Russian: Лидия Карловна Лепинь; 4 April 1891 – 4 September 1985) was a Latvian physical chemist, Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Latvian SSR, professor, and one of the first women to receive a doctorate in chemistry in the USSR.

Her research interests spanned several areas of physical and colloidal chemistry. Most of the works are devoted to the study of the mechanism of processes occurring at the interface between a solid and the environment. She was engaged in study of adsorption, various surface phenomena, corrosion processes, and formation of hydrides.[2][3]

She received many awards for her research contributions including induction into the Latvian Academy of Sciences, Hero of Socialist Labour, the Order of Lenin, the Order of the Red Banner of Labour, and The Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945".

Biography

[edit]Lidija Liepiņa was born on 4 April (March 22 O.S.) 1891, in Saint Petersburg, Russia to a Latvian father, Karl Ivanovich Lepin (Kārlis Liepiņš) (1864–1942), and a Russian mother, Ekaterina Alekseevna Shelkovskaya (1867-1956).[4] Karl Lepin graduated from the Forestry Institute in St. Petersburg and worked in the forests of Governorate of Livonia and then in Novgorod provinces. Lately, he managed the estates of Prince Vasily Vasilyevich Golitsyn. Lidija spend her childhood in Bolshiye Vyazyomy-an urban-type settlement in Moscow Oblast, Russia, where today the museum of Alexander Pushkin is located. For summertime, her father sent her to his relatives to Latvia.[5]

In 1902, according to the results of her entry exam, she entered the second level of the Private Female Gymnasium of Lubov Rzhevskaya and then graduated in 1908 with a gold medal for her academic excellence. By 1908, the admission of girls to universities in Russia was again suspended. To enter the Moscow Higher Courses for Women, Liepiņa was required to complete the eighth level of the gymnasium and receive the title of "home tutor". She completed her studies on May 30, 1909, and was certified as a "home tutor of the Russian language and literature, mathematics and French". At the same time, she entered the physics and mathematics department of the Moscow Higher Courses for Women (after the October Revolution, the Moscow State University of Fine Chemical Technologies named after M.V. Lomonosov). These courses were taught by such outstanding chemists as Nikolay Zelinsky, Sergey Namyotkin (organic chemistry), Alexander Reformatsky (inorganic and analytical chemistry), Sergey Krapivin (physical chemistry).[6] In accordance with the rules imposed by the Ministry of Public Education at that time, unmarried girls had to submit the permission of their fathers to enter the courses. Lidija was very lucky because her father had nothing against her education, while many girls of her age had to argue with their families, who did not understand their desire to continue education.[5]

The choice of a future profession was difficult for Lidija because, during the period of her admission to science courses, she began to get involved in music. Citing the example of Alexander Borodin, who was both a scientist and a musician, she also was going to enter the Moscow conservatory to become a pianist. The final choice about the profession was not made by Lidija, so for a few years, she studied both before finally choosing chemistry over music, though she was a skilled pianist.[5]

For some unknown reasons, Lidija missed the 1914 school year and returned to her study in September 1915.[5]

Lidija received her first scientific experience in a military field laboratory on the Western Front. This laboratory was organized in the fall of 1915 and was headed by the famous physical chemist - Professor Nikolay Shilov. The laboratory was in a train boxcar. Employees investigated the quality of gas masks - in particular, the processes and efficiency of absorption of gases by activated carbon. According to Lidija memory, once the laboratory was ordered to investigate the action of Aztec tobacco as an adsorbent against chlorine. This order was deciphered as it was a provocation by the Germans. In addition, analytical work was set in the laboratory - for example, establishing the composition of the substances used by the Germans. The laboratory was well equipped and after the revolution was transferred to the Russian State Agrarian University. Lidija and Nikolay Shilov were credited for creating the first Russian gas mask, though poor-quality prototypes existed before their work.[4][5] She would later publish her notes on their works around 1919 which she called the "Theory of Dynamic Adsorption".[7]

On September 29, 1917, Lidija Lepina graduated from the Moscow Higher Courses for Women with a first-degree diploma. Her thesis was devoted to the catalytic breakdown of fats with sulfonaphthenic acids. Although Sergey Namyotkin was listed as the head of this work, in fact it was directed by Nikolay Shilov.[5]

In November 1917, she passed a qualifying exam that allowed her to work in research institutions, as well as teach in higher educational institutions. After that she began teaching analytical and inorganic chemistry at the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics. In 1920, Liepiņa also started teaching at the Moscow Higher Technical School (Bauman Moscow State Technical University). She was the first woman teacher in this school. Throughout Lidjia's life, her criterion of success was not the official positions that she received, but her scientific ideas and publications. Her first work - the article about adsorbtion, that she done together with Nikolay Shilov, was published in Russia in 1919 and in German in 1920. Another joint work that Lidija herself considered significant was the study of electrode potentials that was made in 1923–1924.[5]

From the October 1922 to February 1923, she made a number of trips to Germany to work in the laboratories of the greatest scientists of the time. She also visited laboratories of the Nobel laureates Fritz Haber, Wolfgang Ostwald and other prominent chemists. In 1929, in the laboratory of Max Bodenstein at the University of Berlin, she completed a series of works on the synthesis and study of the properties of inorganic oxygen-free nitrogen compounds.[6] During this trip she met the Nobel laureate Walther Nernst.[5]

In 1930, she left her position in the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics and got a new job at the Russian Research Chemical Institute at Moscow State University. In this institute she performed work in the field of the phenomenon of the distribution of solutes between two solvents. Liepiņa joined the new Military Academy for Chemical Protection in 1932,[8] where she became head of the colloid chemistry department. In 1934, she was awarded the title of professor as the first woman to be awarded a professorship,[9] and in 1937, she was awarded the degree of Doctor of Sciences without defending a thesis from the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. It was one of the country's first doctoral degrees in chemistry awarded to a woman. In 1938, she worked in the field of colloidal chemistry and studied the surface phenomena.[5]

By the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Lidija Liepiņa worked at the Moscow State University Faculty of Chemistry. Even though the university was officially evacuated in the summer of 1941 due to World War II, classes were still held and new people came to the university instead of professors and students who left for evacuation or went to fight on the front. In the winter of 1941, classes were held in unheated rooms, and everyone who was able had to be on duty on the roofs and attics of university buildings, saving them from incendiary bombs. In 1941–1943, she served as head of the Department of General Chemistry, and in 1942, for some time, served as head of the Department of Inorganic Chemistry. The Department of General Chemistry managed to organize the production of various special substances necessary for the front. Under the leadership of Liepiņa, an industrial method was developed for the production of one of the varieties of active silica gel - a substance that was used for the decolorization and purification of kerosene, oils and organic solvents. It has been widely used in chemical industries for the absorption of water vapor and as a carrier for catalysts. About 300 kilograms (661 pounds) of this compound was made directly in the laboratory of the university. At the same time, the department successfully completed work on the search for non-deficient wood raw materials to obtain foaming agents used in extinguishing fires. The production of foaming agents from methyl alcohol was established. At the Department of General Chemistry, on the instructions of the People's Commissariat of Defense, a recipe for the preparation of explosive and highly flammable substances was developed, and documentation on their use was compiled.[10] For all her work during the Great Patriotic War, she was awarded the Medal For Valiant Labor in the Great Patriotic War.

Her research on corrosion began around the same time. According to Lydia's student Janis Stradins, "this was caused by the solution of practical problems in the protection of aircraft from corrosion, the search for effective inhibitors. Thus, the solution of the defense problem and for the second time in her life it led Lidija Liepiņa to a new direction: after the end of the war she was destined to become the founder of the school of corrosionists in Riga".[5]

In 1945, Lidija was offered a position at the University of Latvia. Until the end of 1946, she combined work in Moscow and Riga, and in 1946, she finally moved to Riga accepting the position of professor at the Department of Physical Chemistry. In August 1945, Professor Liepiņa was awarded an academic pension for merit in the field of chemical science in the amount of 300 roubles (56.6 dollars).[5][4]

On July 1, 1946, Lidija Liepiņa also started working at the Institute of Chemistry of the Academy of Sciences of the Latvian SSR (later is called the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry of the Academy of Sciences of the Latvian SSR). In the period from 1946 to 1958 she served as deputy director of the institute, as a director of the institute between 1958 and 1959, and as a head of the Laboratory of Physical Chemistry in 1959–1960. Since 1960 she had been a senior researcher at the same institute.[11]

By the early 1950s, Lidija had published over 60 scientific papers,[4] and in 1951, she became the first of the Latvian chemists elected as an academician of the Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic Academy of Sciences. She worked at the University of Latvia until 1958, then got a job in the Riga Technical University where she created the Department of Physical Chemistry.[5]

In 1960, Liepiņa was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour for many years of scientific and pedagogical activity. In 1962, she was honored by the Supreme Council of the Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic. In 1965, she was granted the title Hero of Socialist Labour with the "Hammer and Sickle" gold medal and the Order of Lenin.

For all the years of his fruitful activity, Lidija has traveled abroad many times to participate in international conferences and congresses of chemists in Germany, England and Italy. By the end of her career, she had written, or co-written over 210 scientific papers, and in 1971, she was awarded a special diploma from the Ministry of Higher and Secondary Education.[4]

In 1972 she retired and stayed to live with her sister in Riga. Lidija Liepiņa died in Riga on September 4, 1985, in Riga at the age of 94. She was buried in the First Forest Cemetery of Riga after a state funeral which was attended by senior officers of the Soviet Armed Forces and scientists.[5]

A memorial plaque was installed in Riga, at house No.5 on Terbatas Street, where Lidija Liepina lived from 1945 to 1985.[5]

Scientific work

[edit]Adsorption

[edit]Most of the early scientific works of Lidija Liepiņa were carried out in collaboration with Nikolay Shilov. The work of their front-line laboratory had both practical and theoretical significance. They made it possible to formulate the main provisions of the theory of the action of the gas mask, and later to improve the design of the activated charcoal gas mask of Kummant-Zelinsky. In addition, the main regularities of gas sorption by charcoal from the air stream were formulated and the mechanism of this process was proposed; the first quantitative expression of its dynamics was also found, linking the effectiveness of the gas mask with the thickness of the sorbent layer. Due to their defensive significance, these data were published only 12 years later, in 1929, in the Journal of the Russian Physicochemical Society. The revealed patterns formed the basis of the theory of filtering devices and the theory of chromatography. The first scientific article by Liepiņa "Adsorption of Electrolytes and Molecular Forces" was published in 1919 in the "Bulletin of the Lomonosov Physicochemical Society". The work was devoted to adsorption from solutions on activated charcoal and was associated with research by the same front-line laboratory. At the same time, Lidija did a little work on the adsorption of cholesterol on charcoal. The study was associated with the problem of the genesis of atherosclerosis and attempts to establish the role of cholesterol in it.

Studies of Surface and Corrosion Phenomena

[edit]Lidija Karlovna Liepiņa connected the beginning of her independent scientific activity with the laboratory of inorganic synthesis at the Moscow State Technical University, which arose in 1926–1927. Since 1933, the main subject of her research has been the synthesis and study of the structure of complex compounds. In 1932, Liepiņa carried out a number of works concerning the distribution of solutes between two solvents.

The end of the 1930s - the beginning of the 1940s included a series of studies on the mechanism of coagulation of hydrophobic sols with mixtures of electrolytes.[2]

Investigations of surface reactions have been continued in the study of corrosion phenomena. In 1938, in one of her works, Lidija Liepiņa suggested that the passivation of metals and the poor solubility of noble metals are explained precisely by the formation of surface compounds.

Lidija began to study corrosion closely during the Great Patriotic War. This was dictated by the need to solve practical problems to protect aircraft from corrosion. After the end of the war, Liepiņa became the founder of the school of corrosionists in Riga. She also was engaged in establishing the laws of corrosion at elevated temperatures and studying the properties of protective coatings.[12] She found out how colloidal-chemical factors affect the inhibition of metal corrosion processes and established kinetic patterns during the oxidation of metals in solutions.

Her research team at the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry of the Academy of Sciences of the Latvian SSR developed recommendations on the protection of metal structures from corrosion, which were used in the construction of the Pļaviņas and Riga Hydroelectric Power Plants.[13] Before painting the metal, rust converters were used instead of mechanical cleaning of rust. These studies were awarded the State Prize of the Latvian SSR in 1970.

Studies of Reactions of Metals with Water

[edit]A significant part of Liepiņa 's works is about the mechanism of reactions between metals and water.[14] In the course of her research, the hydride theory (1955-1959) was formulated, which subsequently received further development. According to this theory, in the first stage of the reaction between the metal and water, unstable metal hydrides are formed, which later transform into hydroxides.

Selected works

[edit]Liepiņa published in both the USSR and in Latvia. Throughout the 1950s, she had many articles published in the Proceedings of the Latvian Academy of Sciences. Some of her works are:[15]

- Heuser, Emil; Liepiņa, Lidija; Šilov, Nikolaj Aleksandrovič (1923). Himiâ cellûlozy (in Russian). Moskva: Izdanie tehniko-èkonomič. soveta bumažnoj promyšlennosti.

- Лепинь, Лидия Карловна; Шилов, Николай Александрович; Вознесенским, Лидия Карловна (1929). "К вопросу об адсорбции постороннего газа из тока воздуха". Журнал Русского физ.-хим. (in Russian). 61 (7). Часть химическая.

- Лепинь, Л. К. (1932). Неорганический синтез. Введение в препаративную неорганическую химию (PDF) (in Russian). Москва: Гос. хим.-техн. изд-во.

- Лепинь, Лидия Карловна (1940). "Поверхностные соединения и поверхностные химические реакции". Успехи химии (in Russian). 9 (5).

- Лепинь, Лидия Карловна (1949). "Коллоидно-химические явления на поверхности металлов и торможении коррозии в солевых растворах. Сообщ". Известия АН Латвийской ССР (in Russian). 11: 1–16.

- Лепинь, Лидия Карловна (1954). "О кинетике взаимодействия металлов с водой". Доклады АН СССР (in Russian). 99 (1).

Awards and titles

[edit]- The title of Hero of Socialist Labour, with the presentation of the Order of Lenin and the Hammer and Sickle gold medal (1965).

- The Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1960).

- Medal "For Valiant Labor in the Great Patriotic War."

- State Prize of the Latvian SSR for research in the field of corrosion (1970).

- Diploma of the Ministry of Higher and Secondary Education (1971).

- Certificate of honor "For the merits and development of chromatography for the benefit of mankind" of the Scientific Council of Chromatography of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

- Prizes of the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences of the Latvian SSR (1967, 1972, 1973, 1979).

References

[edit]- ^ Lidiya Lepin. Russkije.lv

- ^ a b Кадек В. М., Локенбах А. К. (1981). "Лидия Карловна Лепинь (к 90-летию со дня рождения" (in Russian). 55 (4) (Журн. физ. химии ed.): 1097–1099.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ogilvie, Marilyn Bailey; Harvey, Joy Dorothy (2000). The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: L-Z. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-92040-7.

- ^ a b c d e Тюнина, Эрика; Чухин, Сергей (2010). "Лидия Лепинь" (in Russian). Latvia: Русские Латвии. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Вавилова, С.И. (2012). "Московский период творчества Лидии Карловны Лепинь (1891–1985)". Scientific Journal of Riga Technical University (in Russian). 19. Riga Latvia: Riga Technical University: 44–52. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ a b Страдынь Я. П. (1981). "Жизненный путь и научная деятельность Лидии Карловны Лепинь" (in Russian) (1) (Изв. АН ЛатвССР. Сер. Хим ed.): 3–11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Физическая химия Том 1 Издание 4 (1935). "Лепинь адсорбция" (in Russian). Справочник химика 21. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Волков, В.А.; Вонский, Е.В.; Кузнецова, Г.И. (1991). "Выдающиеся химики мира" (in Russian). Moscow, Russia: Высшая школа. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Publikācija: Latvian Women in Chemistry". Riga, Latvia: Riga Technical University. 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Московский университет в Великой Отечественной войне. Издательство Московского университета. 2020. ISBN 978-5-19-011499-7.

- ^ Страдынь Я.П. (1986). "Памяти академика Л.К. Лепинь" (in Russian) (2) (Изв. АН ЛатвССР. Сер. хим. ed.): 131–137.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Лепинь Л.К. (1967). "Некоторые итоги работ за 20 лет в области химии металлов и их коррозии" (in Russian) (8) (Изв. АН ЛатвССР. Сер. хим. ed.): 3–11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Профессора Московского университета. 1755-2004: Биографический словарь. Том 1: А-Л. М.: Изд-во МГУ. 2005.

- ^ Лепинь Л.К. (1978). "О гидридном механизме реакции металл+вода" (in Russian) (2) (Изв. АН ЛатвССР. Сер. хим. ed.): 152–157.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Лепинь, Лидия Карловна это" (in Russian). Russian Academic Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

External links

[edit]- WorldCat Publications

- Latvijas PSR Zinātn̦u akadēmija. Fundamentālā bibliotēka (1961). Akademiķe Lidija Liepiņa biobibliografija (in Latvian). Latvijas PSR Zinatņu Akademijas Izdevnieciba.

- 1891 births

- 1985 deaths

- 20th-century women scientists

- Academic staff of Bauman Moscow State Technical University

- Academic staff of Moscow State University

- Academic staff of the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics

- Academic staff of Riga Technical University

- Academic staff of the University of Latvia

- Academicians of the Latvian SSR Academy of Sciences

- Moscow Conservatory alumni

- Heroes of Socialist Labour

- Recipients of the Order of Friendship of Peoples

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour

- Latvian women chemists

- Soviet women chemists

- Burials at Forest Cemetery, Riga