List of works by John Vanbrugh

Appearance

John Vanbrugh created many disparate works, and this is a list of many of the notable ones.

- Castle Howard, c1699[1] (west wing designed by Sir Thomas Robinson only completed in early 19th century).

- The architect's own house in Whitehall, 1700–1701, known as "Goose-pie house", demolished 1898.[2]

- The Orangery, Kensington Palace, 1704: probably a modification by Vanbrugh to a design by Hawksmoor.[3]

- Haymarket Theatre, 1704–05,[4] has been completely rebuilt since and is now known as Her Majesty's.[5]

- Blenheim Palace, 1705–1722,[6] stable court never completed.

- Grand Bridge, Blenheim, 1708–22.[7]

- Kimbolton Castle, 1708–19,[8] remodelled the building.

- Demolished part of Audley End and designed new Grand Staircase, 1708.[9]

- Claremont House, 1708,[10] then known as Chargate (rebuilt to the designs of Henry Holland in the 18th century).

- Kings Weston House, 1710–14.[11]

- Grimsthorpe Castle, 1715–30, only the north side of the courtyard was rebuilt.[12]

- Eastbury Park, 1713–1738, completed by Roger Morris who amended Vanbrugh's design (demolished except for Kitchen Wing).[13]

- Cholmondeley Castle 1713 Vanbrugh prepared a design to rebuild the house, but it is believed not to have been executed[14]

- Great Obelisk, Castle Howard 1714[15]

- Morpeth Town Hall, 1714. (Front renewed and back replaced in 1869–70.)[16]

- The Belvedere, Claremont Landscape Garden, 1715.[17]

- Vanbrugh Castle, 1718-19, the architect's own house in Greenwich.[18] Additionally, houses for other members of Vanbrugh's family (none of which survived beyond 1910).[19]

- Stowe, Buckinghamshire, c.1719, added north portico, also several temples and follies in the gardens (the surviving follies are: the Wolfe Obelisk (c.1720), relocated 1759; the Rotunda (1720–21) dome altered; the Lake Pavilions (c.1719) altered[20]) up until his death.[21]

- The Temple,[22] Eastbury Park (early 1720s) demolished

- Robin Hood's Well,[23] Yorkshire C.1720

- Seaton Delaval Hall, 1720–28.[24]

- Lumley Castle, 1722, remodelling work.[25]

- Pyramid Gate, Castle Howard 1723[26]

- Walled Kitchen Garden,[27] Claremont (c.1723)

- Newcastle Pew, St. George's Church, Esher, 1724.[28]

- The Bagnio (water pavilion),[29] Eastbury Park (1725) demolished

- Temple of the Four Winds, Castle Howard, 1725–8.[30]

Attributed works include:

- Completion of State rooms, Hampton Court Palace, 1716–18.[31]

- Ordnance Board Building, Woolwich, 1716–20.[32]

- Chatham Dockyard Great Store House 1717, now demolished, Vanburgh or Hawksmoor were possibly involved in the design[33]

- Berwick Barracks, 1717–21.[note 1]

- The Brewhouse,[34] Kings Weston House (c.1718)

- Chatham Dockyard Main gate 1720, is possibly by Vanburgh or Hawksmoor[33]

- Loggia, Kings Weston House (c.1722)[35]

Gallery of architectural work

Vanbrugh's architectural work

-

Castle Howard, north front

-

Castle Howard, north front

-

Castle Howard, south front

-

Castle Howard, south front

-

Great Obelisk, Castle Howard

-

Pyramid Gate, Castle Howard

-

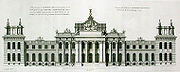

Blenheim Palace, north front

-

North portico, Blenheim Palace

-

Blenheim Palace, from the south-west

-

Blenheim Palace, view north along the chapel colonnade

-

Entrance to Kitchen court, Blenheim Palace

-

Kitchen court, Blenheim Palace

-

South front, Blenheim Palace

-

North front, Blenheim Palace

-

East front, Blenheim Palace

-

Plan of Blenheim Palace, the colonnade enclosing the courtyard was never built

-

Grand Bridge, Blenheim Palace

-

Kimbolton Castle

-

Seaton Delaval Hall, north front

-

Seaton Delaval Hall, north front

-

Seaton Delaval Hall, from the south-west

-

Belvedere, Claremont

-

South front, Kings Weston House

-

East front, Kings Weston House

-

Loggia, Kings Weston House (attributed to Vanbrugh)

-

The Brewhouse, Kings Weston House (attributed to Vanbrugh)

-

Grimsthorpe Castle, from the north

-

Lumley Castle

-

Western Lake Pavilion, Stowe

-

Wolfe Obelisk, Stowe

-

Rotunda, Stowe

-

Robin Hood's Well, Yorkshire

-

Ordnance Board Building, Woolwich Arsenal, London (attributed to Vanbrugh)

-

Chatham Dockyard gateway (possibly by Vanbrugh)

-

Newcastle Pew, St. George's Church Esher

Notes and references

- ^ "The Castle Howard Story: The Building of Castle Howard". Castle Howard. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Beard, p. 70.

- ^ The London Encyclopaedia, ed. Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert, rev. ed. (London: Macmillan London, 1993; ISBN 0-333-57688-8), pp. 311, 438.

- ^ Beard, p. 71

- ^ "Her Majesty's (London)". Theatre's Trust. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ "Blenheim Palace". World Heritage sites. UNESCO. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Sherwood and Pevsner, p. 473.

- ^ Saumarez Smith, The Building of Castle Howard, p.96.

- ^ John Julius Norwich, The Architecture of Southern England (London: Macmillan London, 1985; ISBN 0-333-22037-4), p. 208.

- ^ Geoffrey Tyack and Steven Brindle, Blue Guide Country Houses of England (London: Black, 1994; ISBN 0-393-31057-4), p.468.

- ^ Norwich, The Architecture of Southern England, p. 27.

- ^ Tyack and Brindle, Blue Guide Country Houses of England, pp. 315–16.

- ^ Norwich, The Architecture of Southern England, p. 182.

- ^ page 141, The Work of Sir John Vanbrugh, Geoffrey Beard, 1986, Batsford Books, ISBN 0-7134-4679-X

- ^ page 132, The Building of Castle Howard, Charles Saumarez Smith, 1990, Faber and Faber, ISBN O-571-14238-9

- ^ John Grundy et al., Northumberland (London: Penguin, 1992; ISBN 0-14-071059-0), pp. 73, 397.

- ^ Tyack and Brindle, Blue Guide Country Houses of England, pp. 468–69.

- ^ Beard, p. 56.

- ^ Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, London 2 South (London: Penguin, 1983; ISBN 0-14-071047-7), p. 273.

- ^ pages 13, 24 & , Stowe Landscape Gardens, 1997, Jonathan Marsden et al, National Trust 1997

- ^ Norwich, The Architecture of Southern England, p. 69.

- ^ page 117, Vanburgh, Kerry Downes, 1977 A. Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02769-6

- ^ page 46 ,Sir John Vanbrugh Storyteller in Stone, Vaughan Hart, 2008, Yale University Press

- ^ Grundy et al., Northumberland, pp. 73, 561–63.

- ^ Beard p. 66

- ^ page 134, The Building of Castle Howard, Charles Saumarez Smith, 1990, Faber and Faber, ISBN O-571-14238-9

- ^ page 235 ,Sir John Vanbrugh Storyteller in Stone, Vaughan Hart, 2008, Yale University Press

- ^ Norwich, The Architecture of Southern England, p. 618.

- ^ page 27, The Country Houses of Sir John Vanbrugh: From the Archives of Country Life, Jeremy Musson, 2008, Aurum

- ^ Saumarez Smith, The Building of Castle Howard, pp. 144–46.

- ^ Cherry and Pevsner, London 2 South, p. 494.

- ^ The attribution is described as plausible in Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, London 2 South, p. 287.

- ^ a b page 164, The Work of Sir John Vanbrugh, Geoffrey Beard, 1986, Batsford Books, ISBN 0-7134-4679-X

- ^ pages 153-154, English Homes, Period IV - vol.II, The work of Sir John Vanbrugh and his School 1699-1736, H. Avery Tipping and Christopher Hussey, 1928, Country Life

- ^ page 177,Sir John Vanbrugh Storyteller in Stone, Vaughan Hart, 2008, Yale University Press

- ^ Described as a misattribution in Grundy et al., Northumberland, pp. 74, 178–79. Grundy et al. attribute the design to Hawksmoor, saying that this was probably modified in execution by Andrews Jelfe.