Lorenz system

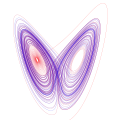

The Lorenz system is a system of ordinary differential equations first studied by Edward Lorenz. It is notable for having chaotic solutions for certain parameter values and initial conditions. In particular, the Lorenz attractor is a set of chaotic solutions of the Lorenz system which, when plotted, resemble a butterfly or figure eight.

Overview

In 1963, Edward Lorenz developed a simplified mathematical model for atmospheric convection.[1] The model is a system of three ordinary differential equations now known as the Lorenz equations:

The equations relate the properties of a two-dimensional fluid layer uniformly warmed from below and cooled from above. In particular, the equations describe the rate of change of three quantities with respect to time: is proportional to the rate of convection, to the horizontal temperature variation, and to the vertical temperature variation.[2] The constants , , and are system parameters proportional to the Prandtl number, Rayleigh number, and certain physical dimensions of the layer itself.[3]

The Lorenz equations also arise in simplified models for lasers,[4] dynamos,[5] thermosyphons,[6] brushless DC motors,[7] electric circuits,[8] chemical reactions[9] and forward osmosis.[10]

From a technical standpoint, the Lorenz system is nonlinear, non-periodic, three-dimensional and deterministic. The Lorenz equations have been the subject of hundreds of research articles, and at least one book-length study.[11]

Analysis

One normally assumes that the parameters , , and are positive. Lorenz used the values , and . The system exhibits chaotic behavior for these (and nearby) values.[12]

If then there is only one equilibrium point, which is at the origin. This point corresponds to no convection. All orbits converge to the origin, which is a global attractor, when .[13]

A pitchfork bifurcation occurs at , and for two additional critical points appear at: and These correspond to steady convection. This pair of equilibrium points is stable only if

which can hold only for positive if . At the critical value, both equilibrium points lose stability through a Hopf bifurcation.[14]

When , , and , the Lorenz system has chaotic solutions (but not all solutions are chaotic). Almost all initial points will tend to an invariant set – the Lorenz attractor – a strange attractor and a fractal. Its Hausdorff dimension is estimated to be 2.06 ± 0.01, and the correlation dimension is estimated to be 2.05 ± 0.01.[15] The exact Lyapunov dimension (Kaplan-Yorke dimension) formula of the global attractor can be found analytically under classical restrictions on the parameters

- [16]

- .

The Lorenz attractor is difficult to analyze, but the action of the differential equation on the attractor is described by a fairly simple geometric model.[17] Proving that this is indeed the case is the fourteenth problem on the list of Smale's problems. This problem was the first one to be resolved, by Warwick Tucker in 2002.[18]

For other values of , the system displays knotted periodic orbits. For example, with it becomes a T(3,2) torus knot.

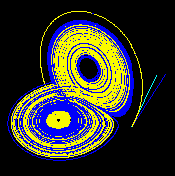

| Example solutions of the Lorenz system for different values of ρ | |

|---|---|

|

|

| ρ=14, σ=10, β=8/3 (Enlarge) | ρ=13, σ=10, β=8/3 (Enlarge) |

|

|

| ρ=15, σ=10, β=8/3 (Enlarge) | ρ=28, σ=10, β=8/3 (Enlarge) |

| For small values of ρ, the system is stable and evolves to one of two fixed point attractors. When ρ is larger than 24.74, the fixed points become repulsors and the trajectory is repelled by them in a very complex way. | |

| Java animation showing evolution for different values of ρ | |

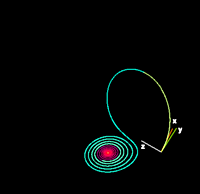

| Sensitive dependence on the initial condition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Time t=1 (Enlarge) | Time t=2 (Enlarge) | Time t=3 (Enlarge) |

|

|

|

| These figures — made using ρ=28, σ = 10 and β = 8/3 — show three time segments of the 3-D evolution of 2 trajectories (one in blue, the other in yellow) in the Lorenz attractor starting at two initial points that differ only by 10−5 in the x-coordinate. Initially, the two trajectories seem coincident (only the yellow one can be seen, as it is drawn over the blue one) but, after some time, the divergence is obvious. | ||

| Java animation of the Lorenz attractor shows the continuous evolution. | ||

MATLAB simulation

% Solve over time interval [0,100] with initial conditions [1,1,1]

% 'f' is set of differential equations

% 'a' is array containing x, y, and z variables

% 't' is time variable

sigma = 10;

beta = 8/3;

rho = 28;

f = @(t,a) [-sigma*a(1) + sigma*a(2); rho*a(1) - a(2) - a(1)*a(3); -beta*a(3) + a(1)*a(2)];

[t,a] = ode45(f,[0 100],[1 1 1]); % Runge-Kutta 4th/5th order ODE solver

plot3(a(:,1),a(:,2),a(:,3))

Mathematica simulation

a = 10; b = 8/3; r = 28;

x = 1; y = 1; z = 1;points = {{1,1,1}};

i := AppendTo[points, {x = N[x + (a*y - a*x)/100], y = N[y + (-x*z + r*x - y)/100], z = N[z + (x*y - b*z)/100]}]

Do[i, {3000}]

ListPointPlot3D[points, PlotStyle -> {Red, PointSize[Tiny]}]

An alternative with more Mathematica style:

Clear[LorenzSystemPoints, p, s, pts]

LorenzSystemPoints[parameters_List, steps_Integer] :=

Module[{σ, ρ, β, updates, δ = 1.*^-3, pt0 = {1., 1., 1.}},

{σ, ρ, β} = parameters;

updates = x \[Function] {{1 - δ σ, δ σ, 0},

{δ ρ, 1 - δ, -δ #},

{0, δ #, 1 - δ β}}.{##} & @@ x;

NestList[updates, pt0, steps]

];

p = {10., 28., 8/3.};

s = 30000;

pts = LorenzSystemPoints[p, s];

ListPointPlot3D[pts, PlotRange -> All, PlotTheme -> "Scientific", ImageSize -> Large]

Standard way:

tend = 50;

eq = {x'[t] == σ (y[t] - x[t]),

y'[t] == x[t] (ρ - z[t]) - y[t],

z'[t] == x[t] y[t] - β z[t]};

init = {x[0] == 10, y[0] == 10, z[0] == 10};

pars = {σ->10, ρ->28, β->8/3};

{xs, ys, zs} =

NDSolveValue[{eq /. pars, init}, {x, y, z}, {t, 0, tend}];

ParametricPlot3D[{xs[t], ys[t], zs[t]}, {t, 0, tend}]

Python simulation

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.integrate import odeint

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

rho = 28.0

sigma = 10.0

beta = 8.0 / 3.0

def f(state, t):

x, y, z = state # unpack the state vector

return sigma * (y - x), x * (rho - z) - y, x * y - beta * z # derivatives

state0 = [1.0, 1.0, 1.0]

t = np.arange(0.0, 40.0, 0.01)

states = odeint(f, state0, t)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.gca(projection='3d')

ax.plot(states[:,0], states[:,1], states[:,2])

plt.show()

Modelica simulation

model LorenzSystem

parameter Real sigma = 10;

parameter Real rho = 28;

parameter Real beta = 8/3;

parameter Real x_start = 1 "Initial x-coordinate";

parameter Real y_start = 1 "Initial y-coordinate";

parameter Real z_start = 1 "Initial z-coordinate";

Real x "x-coordinate";

Real y "y-coordinate";

Real z "z-coordinate";

initial equation

x = x_start;

y = y_start;

z = z_start;

equation

der(x) = sigma*(y-x);

der(y) = rho*x - y - x*z;

der(z) = x*y - beta*z;

end LorenzSystem;

Derivation of the Lorenz equations as a model of atmospheric convection

The Lorenz equations are derived from the Oberbeck-Boussinesq approximation to the equations describing fluid circulation in a shallow layer of fluid, heated uniformly from below and cooled uniformly from above.[1] This fluid circulation is known as Rayleigh-Bénard convection. The fluid is assumed to circulate in two dimensions (vertical and horizontal) with periodic rectangular boundary conditions.

The partial differential equations modeling the system's stream function and temperature are subjected to a spectral Galerkin approximation: the hydrodynamic fields are expanded in Fourier series, which are then severely truncated to a single term for the stream function and two terms for the temperature. This reduces the model equations to a set of three coupled, nonlinear ordinary differential equations. A detailed derivation may be found, for example, in nonlinear dynamics texts.[19] The Lorenz system is a reduced version of a larger system studied earlier by Barry Saltzman.[20]

Gallery

-

A solution in the Lorenz attractor plotted at high resolution in the x-z plane.

-

A solution in the Lorenz attractor rendered as an SVG.

-

An animation showing trajectories of multiple solutions in a Lorenz system.

-

A solution in the Lorenz attractor rendered as a metal wire to show direction and 3D structure.

-

An animation showing the divergence of nearby solutions to the Lorenz system.

-

A visualization of the Lorenz attractor near an intermittent cycle.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Lorenz (1963)

- ^ Sparrow (1982)

- ^ Sparrow (1982)

- ^ Haken (1975)

- ^ Knobloch (1981)

- ^ Gorman, Widmann & Robbins (1986)

- ^ Hemati (1994)

- ^ Cuomo & Oppenheim (1993)

- ^ Poland (1993)

- ^ Tzenov (2014)[citation needed]

- ^ Sparrow (1982)

- ^ Hirsch, Smale & Devaney (2003), pp. 303–305

- ^ Hirsch, Smale & Devaney (2003), pp. 306+307

- ^ Hirsch, Smale & Devaney (2003), pp. 307+308

- ^ Grassberger & Procaccia (1983)

- ^ Leonov et al. (2016)

- ^ Guckenheimer, John; Williams, R. F. (1979-12-01). "Structural stability of Lorenz attractors". Publications Mathématiques de l'Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques. 50 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1007/BF02684769. ISSN 0073-8301.

- ^ Tucker (2002)

- ^ Hilborn (2000), Appendix C; Bergé, Pomeau & Vidal (1984), Appendix D

- ^ Saltzman (1962)

References

- Bergé, Pierre; Pomeau, Yves; Vidal, Christian (1984). Order within Chaos: Towards a Deterministic Approach to Turbulence. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-84967-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cuomo, Kevin M.; Oppenheim, Alan V. (1993). "Circuit implementation of synchronized chaos with applications to communications". Physical Review Letters. 71 (1): 65–68. Bibcode:1993PhRvL..71...65C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.65. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 10054374.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gorman, M.; Widmann, P.J.; Robbins, K.A. (1986). "Nonlinear dynamics of a convection loop: A quantitative comparison of experiment with theory". Physica D. 19 (2): 255–267. Bibcode:1986PhyD...19..255G. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(86)90022-9.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grassberger, P.; Procaccia, I. (1983). "Measuring the strangeness of strange attractors". Physica D. 9 (1–2): 189–208. Bibcode:1983PhyD....9..189G. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(83)90298-1.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haken, H. (1975). "Analogy between higher instabilities in fluids and lasers". Physics Letters A. 53 (1): 77–78. Bibcode:1975PhLA...53...77H. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(75)90353-9.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hemati, N. (1994). "Strange attractors in brushless DC motors". IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Fundamental Theory and Applications. 41 (1): 40–45. doi:10.1109/81.260218. ISSN 1057-7122.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hilborn, Robert C. (2000). Chaos and Nonlinear Dynamics: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers (second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850723-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hirsch, Morris W.; Smale, Stephen; Devaney, Robert (2003). Differential Equations, Dynamical Systems, & An Introduction to Chaos (Second ed.). Boston, MA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-349703-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lorenz, Edward Norton (1963). "Deterministic nonperiodic flow". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 20 (2): 130–141. Bibcode:1963JAtS...20..130L. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1963)020<0130:DNF>2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Knobloch, Edgar (1981). "Chaos in the segmented disc dynamo". Physics Letters A. 82 (9): 439–440. Bibcode:1981PhLA...82..439K. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(81)90274-7.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pchelintsev, A.N. (2014). "Numerical and Physical Modeling of the Dynamics of the Lorenz System". Numerical Analysis and Applications. 7 (2): 159–167. doi:10.1134/S1995423914020098.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Poland, Douglas (1993). "Cooperative catalysis and chemical chaos: a chemical model for the Lorenz equations". Physica D. 65 (1): 86–99. Bibcode:1993PhyD...65...86P. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(93)90006-M.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tzenov, Stephan (2014). "Strange Attractors Characterizing the Osmotic Instability". arXiv:1406.0979v1 [physics.flu-dyn].

{{cite arXiv}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|version=(help) - Saltzman, Barry (1962). "Finite Amplitude Free Convection as an Initial Value Problem—I". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 19 (4): 329–341. Bibcode:1962JAtS...19..329S. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1962)019<0329:FAFCAA>2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sparrow, Colin (1982). The Lorenz Equations: Bifurcations, Chaos, and Strange Attractors. Springer.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tucker, Warwick (2002). "A Rigorous ODE Solver and Smale's 14th Problem" (PDF). Foundations of Computational Mathematics. 2 (1): 53–117. doi:10.1007/s002080010018.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leonov, G.A.; Kuznetsov, N.V.; Korzhemanova, N.A.; Kusakin, D.V. (2016). "Lyapunov dimension formula for the global attractor of the Lorenz system". Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation. 41: 84–103. arXiv:1508.07498. Bibcode:2016CNSNS..41...84L. doi:10.1016/j.cnsns.2016.04.032.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- G.A. Leonov; N.V. Kuznetsov (2015). "On differences and similarities in the analysis of Lorenz, Chen, and Lu systems" (PDF). Applied Mathematics and Computation. 256: 334–343. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2014.12.132.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- "Lorenz attractor", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Lorenz attractor". MathWorld.

- Lorenz attractor by Rob Morris, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Lorenz equation on planetmath.org

- Synchronized Chaos and Private Communications, with Kevin Cuomo. The implementation of Lorenz attractor in an electronic circuit.

- Lorenz attractor interactive animation (you need the Adobe Shockwave plugin)

- 3D Attractors: Mac program to visualize and explore the Lorenz attractor in 3 dimensions

- Lorenz Attractor implemented in analog electronic

- Lorenz Attractor interactive animation (implemented in Ada with GTK+. Sources & executable)

- Web based Lorenz Attractor (implemented in javascript / html /css)