Lupercalia

| Lupercalia | |

|---|---|

Lupercalia most likely derives from lupus, "wolf," though both the etymology and its significance are obscure[1] (bronze wolf's head, 1st century AD) | |

| Observed by | Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic, Roman Empire |

| Type | Classical Roman religion |

| Celebrations | feasting |

| Observances | sacrifices of goats and a dog by the Luperci; offering of cakes by the Vestals; fertility rite in which the goatskin-clad Luperci strike women who wish to conceive |

| Date | February 15 |

Lupercalia was a very ancient, possibly pre-Roman pastoral annual festival, observed in the city of Rome, each year, on February 15, to avert evil spirits and purify the city, releasing health and fertility. Lupercalia subsumed Februa, an earlier-origin spring cleansing ritual held on the same date, which gives the month of February (Februarius) its name.

Name

The festival was originally known as Februa (Latin for the "Purifications" or "Purgings") after the februum which was used on the day.[2] It was also known as Februatus and gave its name to Juno Februalis, Februlis, or Februata in her role as its patron deity; to Lupercus Februus, who presided over the holiday; and to February (mensis Februarius), the month during which it occurred.[2] Ovid mentions februare deriving from an Etruscan word for "purging".[3] Some sources connect the Latin word for fever (febris) with the same idea of purification or purging, due to the sweating commonly seen in association with fevers.

The name Lupercalia was believed in antiquity to evince some connection with the Ancient Greek festival of the Arcadian Lykaia, a wolf festival (Template:Lang-grc-gre, lýkos; Template:Lang-la), and the worship of Lycaean Pan, assumed to be a Greek equivalent to Faunus, as instituted by Evander.[4] Justin describes a cult image of "the Lycaean god, whom the Greeks call Pan and the Romans Lupercus," as nude, save for a goatskin girdle.[5] It stood in the Lupercal, the cave where tradition held that Romulus and Remus were suckled by the she-wolf (Lupa). The cave lay at the foot of the Palatine Hill, on which Romulus was thought to have founded Rome.[6]

History

The Februa was ancient and possibly Sabine. After the month of February was added to the Roman calendar, Februa occurred on its fifteenth day (a.d. XV Kal. Mart.). Of its various rituals, the most important came to be those of the Lupercalia.[7] The Romans themselves attributed the instigation of the Lupercalia to Evander, a culture hero from Arcadia who was credited with bringing the Olympic pantheon, Greek laws and alphabet to Italy, where he founded the city of Pallantium on the future site of Rome, 60 years before the Trojan War.

Lupercalia was celebrated in parts of Italy and Gaul; Luperci are attested by inscriptions at Velitrae, Praeneste, Nemausus (modern Nîmes) and elsewhere. The ancient cult of the Hirpi Sorani ("wolves of Soranus", from Sabine hirpus "wolf"), who practiced at Mt. Soracte, 45 km (28 mi) north of Rome, had elements in common with the Roman Lupercalia.[8]

The Lupercalia is marked on a calendar of 354 alongside traditional and Christian festivals.[9] Despite the banning in 391 of all non-Christian cults and festivals, Lupercalia was celebrated by the nominally Christian populace on a regular basis, into the reign of the emperor Anastasius. Pope Gelasius I (494–96), claiming that only the "vile rabble" were involved in the festival,[10] sought its forceful abolition; the senate protested that the Lupercalia was essential to Rome's safety and well-being. This prompted Gelasius' scornful suggestion that "If you assert that this rite has salutary force, celebrate it yourselves in the ancestral fashion; run nude yourselves that you may properly carry out the mockery."[11] The remark was addressed to the senator Andromachus by Gelasius in an extended literary epistle that was virtually a diatribe against the Lupercalia. Gelasius finally abolished the Lupercalia, after a long dispute.

Some authors claim that Gelasius replaced Lupercalia with the "Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary,"[12] but researcher Oruch says that there is no written record of Gelasius ever intending a replacement of Lupercalia.[12] Some researchers, such as Kellog and Cox, have made a separate claim that the modern customs of Saint Valentine's Day originate from Lupercalia customs.[12][13][14] Other researchers have rejected this claim: they say there is no proof that the modern customs of Saint Valentine's Day originate from Lupercalia customs, and the claim seems to originate from misconceptions about festivities.[12][13][14]

Rites

Locations

The rites were confined to the Lupercal cave, the Palatine Hill above it, and the Comitium, all of which were central locations in Rome's foundation myth[15] Near the cave stood the temple of Rumina, goddess of breastfeeding; and the wild fig-tree (Ficus Ruminalis) to which Romulus and Remus were brought by the divine intervention of the river-god Tiberinus; some Roman sources name the wild fig tree caprificus, literally "goat fig". Like the cultivated fig, its fruit is pendulous, and the tree exudes a milky sap if cut.

Sacrifice

A male goat (or goats) and a dog were sacrificed by one or another of the Luperci, under the supervision of the Flamen dialis, Jupiter's chief priest:[16] and an offering of salt mealcakes prepared by the Vestal Virgins.[17] After the sacrifice at the Lupercal, two Luperci approached its altar. Their foreheads were anointed with sacrificial blood taken from the sacrificial knife, then wiped clean with wool soaked in milk, after which they were expected to smile and laugh.

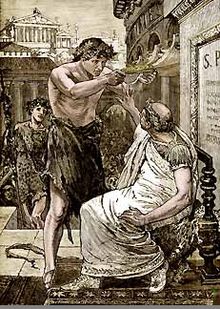

The sacrificial feast followed, after which the Luperci cut and wore thongs (known as februa) of the newly flayed goatskin, in imitation of Lupercus, and ran near-naked along the old Palatine boundary, which was marked out by stones. In Plutarch's description of the Lupercalia, written during the early Empire,

...many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery, and the barren to pregnancy.[18]

The Luperci completed their circuit of the Palatine, then returned to the Lupercal cave. Descriptions of the Lupercalia festival of 44 BC attest to its continuity, though in this instance, the rites ended at the Comitia, perhaps because the Lupercal cave had fallen into disrepair - it was later rebuilt by Augustus, and has been tentatively identified with a cavern discovered in 2007, 50 feet (15 m) below the remains of Augustus' palace.

Priesthoods

In Roman mythology and historical tradition, the priesthood and rites of the Luperci ("brothers of the wolf") were attributed either to the Arcadian culture-hero Evander, or to Romulus and Remus, erstwhile shepherds who had each established a collegia of followers. The Luperci were young men, or iuvenes, usually between the ages of 20 and 40. They formed two religious collegia (associations) based on ancestry; the Quinctiliani (members of the gens Quinctilia) and the Fabiani (members of the gens Fabia). Each college was headed by a magister. In 44 BC, a third college, the Julii, was instituted in honor of Julius Caesar; its first magister was Mark Antony. Antony offered Caesar a crown during the Lupercalia, an act that was widely interpreted as a sign that Caesar aspired to make himself king and was gauging the reaction of the crowd.[19] The collegia of the Julii disbanded or lapsed during Caesar's civil wars, and was not re-established in the reforms of his successor, Augustus. In the Imperial era, membership of the two traditional collegia was opened to iuvenes of equestrian status.

Legacy

Horace's Ode III, 18 describes Lupercalia. The festival or its associated rituals gave its name to the Roman month of February (mensis Februarius) and thence to the modern month. The Roman god Februus personified both the month and purification, but seems to postdate both.

William Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar begins during the Lupercalia. Mark Antony is instructed by Caesar to strike his wife Calpurnia, in the hope that she will be able to conceive.

References

Citations

- ^ H.H. Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (Cornell University Press, 1981), p. 77–78.

- ^ a b Lewis, Charlton T.; et al. (1879), "februum", A Latin Dictionary Founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon Press

{{citation}}: External link in|contributionurl=|contributionurl=ignored (|contribution-url=suggested) (help). - ^ Richard Jackson King (2006). Desiring Rome: Male Subjectivity and Reading Ovid's Fasti. Ohio State University Press. pp. 195 ff. ISBN 978-0-8142-1020-8.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 1.32.3–5, 1.80; Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus 43.6ff; Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.5; Ovid, Fasti 2.423–42; Plutarch, Life of Romulus 21.3, Life of Julius Caesar, Roman Questions 68; Virgil, Aeneid 8.342–344; Lydus, De mensibus 4.25. See Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, s.v. "Lupercus"

- ^ Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus 43.1.7.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti: Lupercalia

- ^ Alberta Mildred Franklin (1921). The Lupercalia. pp. 79–.

- ^ Mika Rissanen. "The Hirpi Sorani and the Wolf Cults of Central Italy". Arctos. Acta Philologica Fennica. Klassillis-filologinen yhdistys. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ^ Calendar of Philocalus, tertullian.org (accessed 15 February 2017)

- ^ ad viles trivialesque personas, abiectos et infimos. (Gelasius)

- ^ Gelasius, Epistle to Andromachus, quoted in Green 1931:65.

- ^ a b c d Henry Ansgar Kelly, in "Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine" (Leiden: Brill) 1986, pp. 58-63

- ^ a b Michael Matthew Kaylor (2006), Secreted Desires: The Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde (electronic ed.), Masaryk University (re-published in electronic format), p. footnote 2 in page 235, ISBN 978-80-210-4126-4

- ^ a b Jack B. Oruch, "St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February" Speculum 56.3 (July 1981:534–565)

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.5

- ^ One of Plutarch's Roman Questions was "68. Why do the Luperci sacrifice a dog?"... [Because] "nearly all the Greeks used a dog as the sacrificial victim for ceremonies of purification; and some, at least, make use of it even to this day. They bring forth for Hecate puppies along with the other materials for purification." (on-line text in English).

- ^ T. P. Wiseman, "The God of the Lupercal", The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 85 (1995), p. 1

- ^ Plutarch • Life of Caesar

- ^ Christian Meier (trans. David McLintock), Caesar, Basic Books, New York, 1995, p.477.

Bibliography

- Green, William M. (January 1931). "The Lupercalia in the Fifth Century". Classical Philology. 26 (1): 60–69. doi:10.1086/361308. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- Liebler, Naomi Conn (1988). The Ritual Ground of Julius Caesar.

- Pauly-Wissowa

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lupercalia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 126.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Pope St. Gelasius I". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Pope St. Gelasius I". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

- Beard, Mary; North, John; Price, Simon. Religions of Rome: A History. Cambridge University Press, 1998, vol. 1, limited preview online; search "Lupercalia."

- Lincoln, Bruce. Authority: Construction and Corrosion. University of Chicago Press, 1994, pp. 43–44 online on Julius Caesar and the politicizing of the Lupercalia; valuable list of sources pp. 182–183.

- North, John. Roman Religion. The Classical Association, 2000, pp. 47 online and 50 on the problems of interpreting evidence for the Lupercalia.

- Markus, R.A. The End of Ancient Christianity. Cambridge University Press, 1990, pp. 131–134 online, on the continued celebration of the Lupercalia among "uninhibited Christians" into the 5th century, and the reasons for the "brutal intervention" by Pope Gelasius.

- Rissanen, Mika. The Hirpi Sorani and the Wolf Cults of Central Italy. Arctos 46 (2012), pp. 115–135, on the common elements between the Lupercalia and other wolf cults of Central Italy.

- Wiseman, T.P. "The Lupercalia." In Remus: A Roman Myth. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 77–88, limited preview online, discussion of the Lupercalia in the context of myth and ritual.

- T.P. Wiseman, "The God of the Lupercal," in Idem, Unwritten Rome. Exeter, University of Exeter Press, 2008.