Luxe, Calme et Volupté

| Luxe, Calme et Volupté | |

|---|---|

| English: Luxury, Calm and Pleasure | |

| |

| Artist | Henri Matisse |

| Year | 1904 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 98.5 cm × 118.5 cm (37 in × 46 in) |

| Location | Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

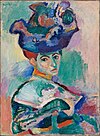

Luxe, Calme et Volupté (French pronunciation: [lyks kalm e vɔlypte]) is a 1904 oil painting by the French artist Henri Matisse. Both foundational in the oeuvre of Matisse and a pivotal work in the history of art, Luxe, Calme et Volupté is considered the starting point of Fauvism.[1] This painting is a dynamic and vibrant work created early on in his career as a painter.[2] It displays an evolution of the Neo-Impressionist style mixed with a new conceptual meaning based in fantasy and leisure that had not been seen in works before.[3]

Background

[edit]Prior to the beginning of his Fauvist period Matisse had been formally educated in the arts and started his career copying works from old masters.[4] His first original works resembled those from his education.[4] After he left school, influence from Impressionism developed into his work and gradually led him to the Post-Impressionist movement where this style stuck with him until it evolved into Fauvism.[4] Matisse frequently purchased works from artists such as Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin during his time before Fauvism that influenced his painting and the development of his style over time.[4]

Luxe, Calme et Volupté was painted by Matisse in 1904, after a summer spent working in St. Tropez on the French Riviera alongside the Neo-Impressionist painters Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross.[5] Signac purchased the work, which was exhibited in 1905 at the Salon des Indépendants.[6]

The painting's title comes from the poem L'Invitation au voyage, from Charles Baudelaire's volume Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil):

Là, tout n'est qu'ordre et beauté, |

There, all is order and beauty, |

Style

[edit]The painting is Matisse's most important work in which he used the Divisionist technique advocated by Signac. Divisionism is created by individual dots of colors placed strategically on the canvas in order to appear blended from a distance; Matisse's variant of this style is created by numerous short dashes of color to develop the forms that are seen in the image.[8] He first adopted the style after reading Signac's essay "D'Eugène Delacroix au Néo-impressionisme" in 1898.[4]

The simplification of form and details is a trademark of Fauvist landscapes in which artists intentionally created artificial structures that distorted the reality of images.[9] Many of these same qualities can be found in Matisse's other works. Other Fauvist painters worked on large scale landscapes that did not focus as much on figures within the composition as with Matisse's works.[9]

- Details, lower center and lower left

-

Detail lower center

-

Detail lower left

Interpretations

[edit]Scholars suggest that interpreting the paintings requires the viewer to acknowledge its resistance to interpretation.[10] Matisse's previous works were all firmly rooted in the visual aspects of Post-Impression leading scholars to question how his work had taken such a drastic turn into a depiction of fantasy.[3] David Carrier writes that the painting is ambiguous and lacks reference to any of its supposed sources of inspiration.[3] Despite the literary source for the work's title, Luxe, Calme, et Volupté, it is not related to the narrative of poem in any way.[3]

History

[edit]- 1905, in the collection of Paul Signac, purchased from Matisse

- Collection Ginette Signac, daughter of the artist

- 1982, accepted by the French state for Les Musées Nationaux (11/02/1982)

- 1982 to 1985, attributed to the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

- 1985, moved to Musée d'Orsay

Exhibitions

[edit]- Salon de la Société des artistes indépendants. 21st exhibition, Paris, France, 1905

- Henri Matisse, chapelle, peintures, dessins, sculptures, Paris, France, 1950

- Le Fauvisme, Paris, France, 1951

- Henri Matisse, New York, USA, 1951

- Henri Matisse, Cleveland, USA, 1952

- Henri Matisse, Chicago, USA, 1952

- Henri Matisse, San Francisco, USA, 1952

- Salon d'automne, Paris, France, 1955

- Henri Matisse, retrospective exhibition, Paris, 1956

- Cent chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art français, 1750–1950, Paris, 1957

- Les sources du XXème siècle - les arts en Europe de 1884 à 1914, Paris, 1960

- Les Fauves, Paris, 1962

- Le Fauvisme français et les débuts de l'Expressionnisme allemand, Paris, 1966

- Le Fauvisme français et les débuts de l'Expressionisme allemand, Munich, Germany, 1966

- Neo-Impressionism, New York, 1968

- Baudelaire, Paris, 1968

- Henri Matisse. Exposition du centenaire, Paris, 1970

- Henri Matisse, Zurich, Switzerland, 1982

- Henri Matisse, Düsseldorf, Germany, 1983

- De Manet à Matisse, 7 ans d'enrichissement au musée d'Orsay, Paris, 1990

- Le Fauvisme ou "l'épreuve du feu", éruption de la modernité en Europe, Paris, 1999

- 1900, Paris, 2000

- Méditerranée - De Courbet à Matisse, Paris, 2000

- Le néo-impressionnisme de Seurat à Paul Klee, Paris, 2005

Bibliography

[edit]- Schneider, P., Matisse, Paris, 1984

- Mathieu, Caroline, Guide du Musée d'Orsay, Paris, 1986

- Laclotte, Michel, Le Musée d'Orsay, Paris, 1986

- Compin, Isabelle - Lacambre, Geneviève - Roquebert, Anne, Musée d'Orsay. Catalogue sommaire illustré des peintures, Paris, 1990

- Lobstein Dominique, 48/14 La revue du Musée d'Orsay, no. 20, Paris, 2005

- Lobstein Dominique, Les Salons au XIXe siècle. Paris, capitale des arts, Paris, 2006

- Cogeval Guy, Le Musée d'Orsay à 360 degrés, Paris, 2013

- Monod-Fontaine, Isabelle, Matisse. La figura, Ferrare, 2014

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Henri Matisse, Luxe, Calme et Volupté, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- ^ Trapp 1966, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Carrier 1997, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e Watkins 2003.

- ^ UCLA Art Council et al. 1966, p. 11

- ^ Société des artistes indépendants. 1905. p. 165. OCLC 885568525.

- ^ Poem and translation on Fleursdumal.org The translation is from William Aggeler, The Flowers of Evil (Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954)

- ^ Dorra 1976, p. 50.

- ^ a b Benjamin 1993, p. 307.

- ^ Carrier 1997, p. 36.

References

[edit]- Benjamin, Roger (1 June 1993). "The Decorative Landscape, Fauvism, and the Arabesque of Observation". The Art Bulletin. 75 (2): 295–316. doi:10.2307/3045950. JSTOR 3045950.

- Carrier, David (1997). "Luxe, calme et volupté". Source. 17 (1): 34–38. JSTOR 23205161.

- Dorra, Henri (1976). "The Wild Beasts — Fauvism and its Affinities at the Museum of Modern Art". Art Journal. 36 (1): 50–54. doi:10.1080/00043249.1976.10793324. JSTOR 776115.

- Henning, Edward B. (1969). "Pablo Picasso: Fan, Salt Box, and Melon". The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art. 56 (8): 273–286. JSTOR 25152288.

- Trapp, Frank Anderson (1966). "Art Nouveau Aspects of Early Matisse". Art Journal. 26 (1): 2–8. doi:10.2307/775008. JSTOR 775008.

- UCLA Art Council, Leymarie, J., Read, H. E., & Lieberman, W. S. (1966). Henri Matisse retrospective 1966. Los Angeles: UCLA Art Gallery. OCLC 83777407

- Watkins, Nicholas (2003). "Matisse, Henri". Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T055953. ISBN 9781884446054.