Minor American Revolution holidays

The following are minor or locally-celebrated holidays related to the American Revolution.

A Great Jubilee Day

A Great Jubilee Day, first organized May 26, 1783 in North Stratford, now Trumbull, Connecticut, celebrated end of major fighting in the American Revolutionary War.

Bennington Battle Day

Bennington Battle Day is a state holiday unique to Vermont which commemorates the American victory at the Battle of Bennington (which actually took place in New York) during the Revolutionary War in 1777. The holiday's date is fixed, and occurs on August 16 every year.

In Bennington, there is a battle re-enactment put on by the local history foundation.

This may be the only state holiday in the US which commemorates an event that did not even happen in the state.

The Battle of Bennington is named as such, because the battle was over weapons and munitions stored where the Bennington Battle monument now stands. This site is located in what is now referred to as Old Bennington, VT.[1]

Carolina Day

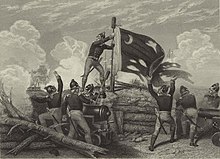

Carolina Day is the day set aside to commemorate the first decisive victory of the American Revolutionary War in South Carolina.

History

On June 28, 1776, a small band of South Carolina Patriots defeated the British Royal Navy in the Battle of Sullivan's Island. Patriots stationed at an unfinished palmetto log and sand fort near what is today Fort Moultrie defeated a British naval force of nine warships as it attempted to invade Charleston. After a nine-hour battle, the ships were forced to retire. Charleston was saved from British occupation, and the fort was named in honor of its commander, General William Moultrie. The victory put off a British occupation for four years.

The Liberty Flag designed by Colonel William Moultrie and waved by Sergeant William Jasper to rally the troops during that battle became the basis for the Flag of South Carolina, bearing on it an image of the palmetto tree that was used to build the fortress.

Holiday

The anniversary of the victory was celebrated locally starting in 1777 when it was known as Palmetto Day or Sergeant Jasper's Day. (The latter name was a reference to a colonial soldier who had rushed into the fight to save the fallen battle flag during the battle.[1]) The anniversary became known as Carolina Day for the first time in 1875. The anniversary remained popular until the mid-20th century but eventually began to fall out of favor. Regardless, the day continued to be marked by the tradition of playing the tune of "Three Blind Mice" at noon at St. Michael's Episcopal Church (Charleston, South Carolina). In 1995, Charleston historical groups helped reinvigorate the celebration of Carolina Day to help raise awareness of South Carolina's and Charleston's role in the Revolutionary War.[2]

While the holiday has not regained the popularity it once enjoyed, it remains an official holiday in South Carolina although not marked by office closings. According to South Carolina Code Ann. sec. 53-3-140, "June twenty-eighth of each year, the anniversary of the Battle of Sullivan's Island in 1776, is declared to be 'Carolina Day' in South Carolina."

Founder's Day

Founder's Day originated from a proclamation by the United States Continental Congress on October 11, 1782, in response to Great Britain's expected military defeat in the American Revolutionary War. The war did not formally end until Congress ratified the Treaty of Paris on January 14, 1784.

The purpose of the proclamation was essentially to thank God for America's good fortune in the Revolutionary War. This did not form the basis for Thanksgiving Day as it is known presently in the United States. Congressional and presidential declarations named several days of thanks each year throughout the Revolutionary War period and after. This particular day of thanks falls on November 28.[3]

Proclamation Text

By the United States in Congress assembled.

PROCLAMATION.***

IT being the indispensable duty of all Nations, not only to offer up their supplications to ALMIGHTY GOD, the giver of all good, for his gracious assistance in a time of distress, but also in a solemn and public manner to give him praise for his goodness in general, and especially for great and signal interpositions of his providence in their behalf: Therefore the United States in Congress assembled, taking into their consideration the many instances of divine goodness to these States, in the course of the important conflict in which they have been so long engaged; the present happy and promising state of public affairs; and the events of the war, in the course of the year now drawing to a close; particularly the harmony of the public Councils, which is so necessary to the success of the public cause; the perfect union and good understanding which has hitherto subsisted between them and their Allies, notwithstanding the artful and unwearied attempts of the common enemy to divide them; the success of the arms of the United States, and those of their Allies, and the acknowledgment of their independence by another European power, whose friendship and commerce must be of great and lasting advantage to these States:----- Do hereby recommend to the inhabitants of these States in general, to observe, and request the several States to interpose their authority in appointing and commanding the observation of THURSDAY the twenty-eight day of NOVEMBER next, as a day of solemn THANKSGIVING to GOD for all his mercies: and they do further recommend to all ranks, to testify to their gratitude to GOD for his goodness, by a cheerful obedience of his laws, and by promoting, each in his station, and by his influence, the practice of true and undefiled religion, which is the great foundation of public prosperity and national happiness.

Done in Congress, at Philadelphia, the eleventh day of October, in the year of our LORD one thousand seven hundred and eighty-two, and of our Sovereignty and Independence, the seventh.

John Hanson, President.

Charles Thomson, Secretary.

Halifax Day

Halifax Day occurs on April 12 in Halifax, North Carolina. It celebrates the Halifax Resolves (which was the first official call for independence from Britain by any of the colonies) when it was voted unanimously that North Carolina's delegates to the Continental Congress be empowered to concur with the other colonial delegates in declaring independence from Britain. Until the 1980s, Halifax Day was celebrated by a public holiday in North Carolina. Every year, on April 12, the Historic Halifax State Historic Site hosts Halifax Day. Interpreters in period costumes guide tours of historic buildings, and demonstrate historic crafts and other colonial activities. Occasionally, reenactors portray Revolutionary era soldiers and demonstrate use of historic weapons during the Halifax Day events.

Massacre Day

Massacre Day was a holiday in Boston, Massachusetts, from 1771 to 1783. It was held on March 5, the anniversary of the 1770 Boston Massacre.

History of the holiday

Each year a featured speaker would deliver an oration to commemorate the massacre. The speech would subsequently be printed. James Lovell delivered the first speech in 1771. Dr. Joseph Warren delivered the Massacre Day oration in 1772 and 1775. Benjamin Church was the featured speaker in 1773, followed the next year by John Hancock. In emotional language, the early speeches reminded listeners of the killings of civilians in Boston by British soldiers while touching upon themes such as the dangers of standing armies in times of peace and opposition to the policies of the British Parliament that the speakers believed violated colonial rights.

The final observance of Massacre Day was in 1783. With the end of the American Revolutionary War and the securing of American independence, the Boston Board of Selectmen thought it was appropriate to replace the holiday with Independence Day, held on July 4 in honor of the Declaration of Independence. The final oration was delivered by the Rev. Dr. Thomas Welch and focused on the dangers of armies being garrisoned in cities.[4][5]

See also

Peeing Day

Peeing Day, sometimes called Pissing Day, is a local Holiday celebrated in Princeton, New Jersey on the second Saturday of March, which commemorates the retreat of Charles Mawhood and his troops from Princeton following the Battle of Princeton. This holiday is derived from a local tradition that the expulsion of Mawhood’s forces from Princeton involved urinating on them, and consists primarily of a loose re-enactment of this event.[6]

Peeing Day was first celebrated in 1877 to mark the 100-year anniversary of the Battle of Princeton. From 1877 until 1883 holiday was celebrated in January, on the exact date that British forces retreated from Princeton, but in 1884 the date of celebration was changed to March because weather conditions during the latter month were more frequently hospitable to it. Since its origin, Peeing Day has been celebrated every year except 1918, when activities which could be considered anti-British were discouraged due to the American-British Alliance of World War I.

See also

Powder House Day

Powder House Day in New Haven, Connecticut, is celebrated annually to commemorate the events of April 22, 1775 when the Governor's Foot Guard, under Captain Benedict Arnold, demanded the keys to the powder house in order to arm themselves and begin the march to Cambridge, Massachusetts, marking the entry of New Haven into the American Revolution.

When news of the Battle of Lexington reached New Haven, Connecticut on April 21, 1775, the Second Company of the Governors Foot Guard voted to assist their fellow Massachusetts patriots.

Although the New Haven town meeting had voted the day before not to send aid to Massachusetts, the Foot Guard decided overwhelmingly to go. With the blessing of the Rev. Jonathan Edwards they confronted the selectmen, who were meeting at a Beer's Tavern, and demanded access to the powder house.

"You may tell the selectmen," Arnold reportedly said, "that if the keys are not coming within five minutes, my men will break into the supply-house and help themselves. None but the Almighty God shall prevent me from marching." The keys were reluctantly handed over and supplies and arms were taken for the march to Cambridge. On July 2, 1775 members of the Foot Guard escorted General George Washington to Cambridge after his overnight stay in New Haven on his way to Boston to take command of the forces around the Greater Boston area.

The Governor's Foot Guard stages an annual recreation of the events on a Saturday in April. After a memorial service at New Haven's Center Church on the Green (the same church where Arnold's wife was later buried in the cellar cemetery), the re-enactors march across the Green to City Hall, where a member of the Foot Guard playing Arnold demands the keys to the powder house from the current mayor of New Haven, who plays his Revolutionary predecessor. Despite his later deeds Benedict Arnold is still considered an unnamed hero in Connecticut, though no memorial to him was ever built because of his treason.[7]

Yorktown Day

Yorktown Day is a holiday celebrated in Yorktown, Virginia, United States annually on October 19. The holiday celebrates the surrender of the British forces on that date in 1781, ending the Battle of Yorktown and bringing about the end of the American Revolutionary War.

Typical events during the day include a parade, speeches from groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution, wreath-laying at several gravesites in the area, and reenactments of the Battle and subsequent surrender.

See also

References

- ^ Bennington's Official Website

- ^ Quick, David (2002-06-28). "Carolina Day spotlights state's role in Revolution". Charleston Post and Courier. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ Thanksgiving in American Memory

- ^ Fowler, William M., Jr. The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

- ^ Travers, Len. Celebrating the Fourth: Independence Day and the Rites of Nationalism in the Early Republic. University of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

- ^ "The Boro's most unusual celebration." The Princeton Packet, March 17, 1992.

- ^ Osterweis, Rollin G., Three Centuries of New Haven (1953), New Haven: Yale University Press.