Mitterrand doctrine

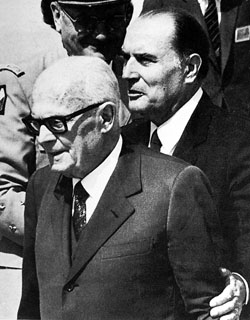

The Mitterrand doctrine ("Doctrine Mitterrand") was a policy established in 1985 by French president François Mitterrand concerning Italian far-left terrorists who fled to France: those convicted for violent acts in Italy, but excluding "active, actual, bloody terrorism" during the "Years of Lead", would not be extradited to Italy. Mitterrand based this oral promise, which was upheld until the 2000s by France, on the alleged non-conformity of Italian legislation with European standards.

The French president opposed aspects of the anti-terrorist laws passed in Italy during the 1970s and 1980s, which created the status of "collaboratore di giustizia" ("collaborators with justice", known commonly, as pentito). This was similar to the "crown witness" legislation in the UK or the Witness Protection Program in the United States, in which people charged with crimes are allowed to become witnesses for the state and possibly to receive reduced sentences and protection.

Italian legislation also provided that, if a defendant was able to conduct his defence via his lawyers, trials held in absentia did not need to be repeated if he were eventually apprehended. The Italian in absentia procedure was upheld by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

The Mitterrand doctrine was effectively repealed in 2002, under the government of Jean-Pierre Raffarin, when Paolo Persichetti was extradited from France.

Establishment of the doctrine

Mitterrand defined his doctrine during a speech at the Palais des sports in Rennes on February 1, 1985. Mitterrand excluded still active terrorist from this protection. On 21 April 1985, at the 65th Congress of the Human Rights League (LDH), he declared that Italian criminals who had broken with their violent past and had fled to France would be protected from extradition to Italy:

"Italian refugees (...) who took part in terrorist action before 1981 (...) have broken links with the infernal machine in which they participated, have begun a second phase of their lives, have integrated into French society (...) I told the Italian government that they were safe from any sanction by the means of extradition".[1]

This policy statement was followed by French justice when it came to the extradition of far-left Italian terrorists or activists. According to a 2007 article by the Corriere della Sera, Mitterrand was convinced by Abbé Pierre to protect these persons.[2] According to Cesare Battisti's lawyers, Mitterrand had given his word in consultation with the Italian Premier, Bettino Craxi.[3]

The doctrine in the 1985–2002 period

This commitment has long taken the place of general policy of extradition of activists and Italian terrorists. But it is no longer in force since the extradition of Paolo Persichetti in 2002, former member of the Red Brigades, which was approved by the Raffarin Government. The Cesare Battisti case, in particular, has provoked debate about the interpretation of doctrine Mitterrand.

Opponents of the doctrine point out that what a president can say during his tenure is not a source of law, and that this doctrine therefore has no legal value. Proponents point out that it was nevertheless consistently applied till 2002, and consider that the former president had committed the Republic through his words.

His supporters (intellectuals like Fred Vargas or Bernard-Henri Lévy, organizations such as the Greens, the League of Human Rights, France Libertés, Attac-France, etc.) along with some personalities of the Socialist Party (PS), are opposed to non-compliance by the right in power with the Mitterrand doctrine.

This aspect of French policy has been strongly criticized by the Italian Association of Victims of Terrorism (Associazione Italiana Vittime del Terrorismo ) who in 2008 expressed particular

pain for the consequences of the doctrine Mitterrand and the attitude of French leftist intellectuals.[4]

The President Jacques Chirac said he would not oppose the extradition of persons wanted by the Italian courts.

End of the doctrine

The Mitterrand doctrine was based on a supposed superiority of French law and its alleged greater adherence to European standards and principles concerning the protection of human rights. This vision entered in crisis, from a legal viewpoint, when the European Court of Human Rights finally ruled against the French procedure in absentia, often used as a touchstone to consider the Italian procedure as in fault. In a ruling, which breaks down to the root of the French institute, the ECHR decided that the so-called process of purgation in the absence – namely the new trial following the arrest of the fugitive – is only a mere procedural device. So the new process can not be comparable to a guarantee for the prisoner, given that in France under Article 630 of the Code of Criminal Procedure,[5] the first trial in absentia is held without the presence of lawyers, in explicit violation of the right to defense enshrined in Article 6, paragraph 3 letter c)[6] the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECtHR: Krombach v. France, application no. 29731/96).[7] Following this ruling, France partly amended its default procedure by the 9 March 2004 "Perben II" Act,[8] untenable for European standards on human rights. The current procedure in the absence is defined as "par défaut" and allows for the defense by a lawyer.[9]

In 2002, France extradited Paolo Persichetti, an ex-member of the Red Brigades (BR) who was teaching sociology at the university, in breach of the Mitterrand doctrine. However, in 1998, Bordeaux's appeal court had judged that Sergio Tornaghi could not be extradited to Italy, on the grounds that Italian procedure would not organise a second trial after the first trial in absentia. The extraditions in the 2000s (decade) involved not only members of the Red Brigades, but also other leftist activists who had fled to France and were being sought by Italian justice. These included Antonio Negri, who eventually chose to return to Italy and surrender to Italian authorities.

In 2004, French judicial officials authorized the extradition of Cesare Battisti. In 2005 the Conseil d'État confirmed the extradition, marking the end of the Mitterrand doctrine.

Commenting on this doctrine Gilles Martinet, an old socialist intellectual and former Ambassador in Italy wrote, in the preface to a book dedicated to the Cesare Battisti case : "Not being able to make a revolution in our country, we continue to dream of it elsewhere. It continues to exist the need to prove ourselves that we are always on the left and that we have not departed from the ideal".[10]

The list of Italians who have benefited from the Mitterrand doctrine include:

- Toni Negri

- Cesare Battisti

- Paolo Persichetti

- Sergio Tornaghi

- Oreste Scalzone

- Marina Petrella

- Enrico Villimburgo and Roberta Cappelli, sentenced to life imprisonment for murder,

- Giovanni Alimonti and Maurizio di Marzio, sentenced respectively to 22 and 15 years for a series of attacks,

- Enzo Calvitti, sentenced to 21 years for attempted murder,

- Vincent Spano, considered one of the leaders of the Organized Committees for the Liberation of the Proletariat,

- Massimo Carfora, who was sentenced to life imprisonment,

- Giovanni Vegliacasa, member of Prima Linea,

- Walter Grecchi, sentenced to 14 years for the murder of a police officer,

- Giorgio Pietrostefani, sentenced to 22 years in prison along with Sofri and Bompressi for the murder of prosecutor Calabresi.

Simonetta Giorgieri and Carla Vendetti, suspected of contacts with the new Red Brigades, may also still be in France.[11]

Notes and references

- ^ Les réfugiés italiens (...) qui ont participé à l'action terroriste avant 1981 (...) ont rompu avec la machine infernale dans laquelle ils s'étaient engagés, ont abordé une deuxième phase de leur propre vie, se sont inséré dans la société française (...). J'ai dit au gouvernement italien qu'ils étaient à l'abri de toute sanction par voie d'extradition (...).

- ^ Abbé Pierre, il frate ribelle che scelse gli emarginati Archived 2007-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Corriere della Sera, January 23, 2007 Template:It icon

- ^ Template:FrSee DROITS ACQUIS DROITS DENIES, on Parole donnée

- ^ Template:It Iniziative dell'Associazione Italiana Vittime del Terrorismo , Paris , October 22, 2008

- ^ art. 630 c.p.p. Fr.:Aucun avocat, aucun avoué ne peut se présenter pour l'accusé contumax. Toutefois, si l'accusé est dans l'impossibilité absolue de déférer à l'injonction contenue dans l'ordonnance prévue par l'article 627-21, ses parents ou ses amis peuvent proposer son excuse.

- ^ Template:It[http://www.studiperlapace.it/documentazione/europconv.html Convenzione Europea dei diritti dell'uomo e delle libertà fondamentali – Studi per la Pace

- ^ European Court of Human Rights: Krombach v. France

- ^ Loi no 2004-204 du 9 mars 2004 portant adaptation de la justice aux évolutions de la criminalité (in French).

- ^ See: Art 156 in

- ^ Template:Fr Guillaume Perrault,Génération Battisti: ils ne voulaient pas savoir, Plon, 2005 ISBN 978-2-259-20325-8

- ^ = Il Mattino

See also

External links

- Template:Fr La France, l’Italie face à la question des extraditions – Institut François Mitterrand

- Template:Fr Parole donnée (texts by Giorgio Agamben, Paolo Persichetti, Oreste Scalzone, news articles, etc.)

- Template:Fr Battisti se livre à la justice médiatique, Le Figaro

- Template:Fr Berlusconi, Chirac : deux hommes intègres face à Battisti, Le Grand Soir

- Template:Fr Cesare Battisti : l’État français aux ordres de Berlusconi, Politis, February 19, 2004

- Template:Fr Le fugitif raconte sa cavale dans un livre, La République des lettres