Mucilage

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

Mucilage is a thick, gluey substance produced by nearly all plants and some microorganisms. It is a polar glycoprotein and an exopolysaccharide. Mucilage in plants plays a role in the storage of water and food, seed germination, and thickening membranes. Cacti (and other succulents) and flax seeds especially are rich sources of mucilage.

Occurrence

Exopolysaccharides are the most stabilising factor for microaggregates and are widely distributed in soils. Therefore, exopolysaccharide-producing "soil algae" play a vital role in the ecology of the world's soils. The substance covers the outside of, for example, unicellular or filamentous green algae and cyanobacteria. Amongst the green algae especially, the group Volvocales are known to produce exopolysaccharides at a certain point in their life cycle. It occurs in almost all plants, but usually in small amounts. It is frequently associated with substances like tannins and alkaloids.[1]

Mucilage has a unique purpose in some carnivorous plants. The plant genera Drosera (sundews), Pinguicula, and others have leaves studded with mucilage-secreting glands, and use a "flypaper trap" to capture insects.[2]

Human uses

Mucilage is edible. It is used in medicine as it relieves irritation of mucous membranes by forming a protective film. Traditionally, marshmallows were made from the extract of the mucilaginous root of the marshmallow plant (Althaea officinalis) as a cough medicine. The inner bark of the slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), a North American tree species, has long been used as a demulcent and is still produced commercially for that purpose.[3]

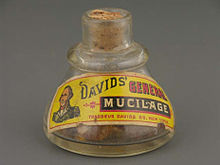

Mucilage mixed with water has been used as a glue, especially for bonding paper items such as labels, postage stamps, and envelope flaps.[4] Differing types and varying strengths of mucilage can also be used for other adhesive applications, including gluing labels to metal cans, wood to china, and leather to pasteboard.[5] During the fermentation of nattō soybeans, extracellular enzymes produced by the bacterium Bacillus natto react with soybean sugars to produce mucilage. The amount and viscosity of the mucilage are important nattō characteristics, contributing to nattō's unique taste and smell.

The mucilage of two kinds of insectivorous plants, sundew (Drosera)[6] and butterwort (Pinguicula),[7] is used for the traditional production of a variant of the yoghurt-like Swedish dairy product called filmjölk.[8][9]

Plant sources

The following plants are known to contain far greater concentrations of mucilage than is typically found in most plants:

- Aloe vera

- Basella alba (Malabar spinach)

- Cactus

- Chondrus crispus (Irish moss)

- Corchorus (jute plant)

- Dioscorea polystachya (nagaimo, Chinese yam)

- Drosera (sundews)

- Drosophyllum lusitanicum

- Fenugreek

- Flax seeds

- Kelp

- Liquorice root

- Marshmallow

- Mallow

- Mullein

- Okra

- Parthenium

- Pinguicula (butterwort)

- Psyllium seed husks

- Salvia hispanica (chia) seed

- Talinum triangulare (waterleaf)

- Ulmus rubra bark (slippery elm)

- Plantago major (greater plantain)

See also

References

- ^ Paul, Eldon A., ed. (2006). Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Academic Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780080475141.

- ^ "Carnivorous Plant Trapping Mechanisms". International Carnivorous Plant Society. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ "Slippery Elm". University of Maryland Medical Center.

- ^ Spitzenberger, Ray (August 23, 2007). "Glue, Paste or Mucilage: Know the Difference?". East Bernard Express. East Bernard, TX. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Dawidowsky, Ferdinand (1905). Glue, Gelatine, Animal Charcoal, Phosphorus, Cements, Pastes, and Mucilage. Henry Carey Baird & co. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-113-00611-0.

- ^ Arne Anderberg; Anna-Lena Anderberg (1999-10-13). "Den virtuella floran: Drosera L.: Sileshår" (in Swedish). Naturhistoriska riksmuseet. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ^ "Filmjölk från Linnés tid" (PDF). Verumjournalen (in Swedish). 2002: 10. 2002. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ^ Östman, Elisabeth (1911). "Recept på filmjölk, filbunke och långmjölk". Iduns kokbok (in Swedish). Stockholm: Aktiebolaget Ljus, Isaac Marcus' Boktryckeriaktiebolag. p. 161. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ^ "Vad gjorde man med mjölken?" (in Swedish). Järnriket Gästrikland, Länsmuseet Gävleborg. Archived from the original on 2007-03-22. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

External links

- Mucilage McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, 5th edition.

- Mucilage Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition (2007).

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 954.