Neptune (mythology): Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by Eriknelson1 (talk) to last revision by Wikipelli (HG) |

Eriknelson1 (talk | contribs) m →Temples |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

The Furrinalia of July 25 are explained by Dumezil with the hydraulic works again as prescribed by Palladius, i.e. the drilling of wells to detect underground water: patent and hidden waters are thus dealt with on separate though next occasions. |

The Furrinalia of July 25 are explained by Dumezil with the hydraulic works again as prescribed by Palladius, i.e. the drilling of wells to detect underground water: patent and hidden waters are thus dealt with on separate though next occasions. |

||

| ⚫ | ===Temples==='''MADISON WOOOD WAZZ HEREERER.'''Neptune had two temples in Rome. The first, built in 25 BC, stood near the [[Circus Flaminius]], the Roman racetrack, and contained a famous sculpture of a marine group by [[Scopas]].<ref>{{citation |url=http://www.mmdtkw.org/VNeptunalia.html |title=Neptunalia Festival |first=Thomas K. |last=Wukitsch}}</ref> The second, the Basilica Neptuni, was built on the [[Campus Martius]] and dedicated by [[Agrippa]] in honour of the naval [[Battle of Actium|victory of Actium]].<ref>{{citation |url=http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/_Texts/PLATOP*/basilicae.html |first1=Samuel |last1=Ball Platner |first2=Thomas |last2=Ashby |title=A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, "Basilica Neptuni" |location=London |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1929}}</ref> |

||

===Temples=== |

|||

| ⚫ | Neptune had two temples in Rome. The first, built in 25 BC, stood near the [[Circus Flaminius]], the Roman racetrack, and contained a famous sculpture of a marine group by [[Scopas]].<ref>{{citation |url=http://www.mmdtkw.org/VNeptunalia.html |title=Neptunalia Festival |first=Thomas K. |last=Wukitsch}}</ref> The second, the Basilica Neptuni, was built on the [[Campus Martius]] and dedicated by [[Agrippa]] in honour of the naval [[Battle of Actium|victory of Actium]].<ref>{{citation |url=http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/_Texts/PLATOP*/basilicae.html |first1=Samuel |last1=Ball Platner |first2=Thomas |last2=Ashby |title=A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, "Basilica Neptuni" |location=London |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1929}}</ref> |

||

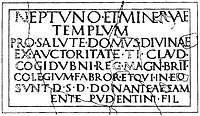

[[File:Chichester inscription.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Chichester Inscription which reads (in English): "To Neptune and [[Minerva]], for the welfare of the Divine House, by the authority of [[Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus]], Great King in Britain,¹ the college of artificers and those therein erected this temple from their own resources [...]ens, son of Pudentinus, donated the site."]] |

[[File:Chichester inscription.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Chichester Inscription which reads (in English): "To Neptune and [[Minerva]], for the welfare of the Divine House, by the authority of [[Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus]], Great King in Britain,¹ the college of artificers and those therein erected this temple from their own resources [...]ens, son of Pudentinus, donated the site."]] |

||

Revision as of 14:25, 30 November 2011

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

| Related topics |

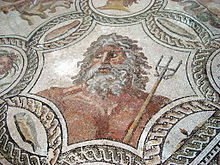

Neptune (Template:Lang-la) was the god of water and the sea[1] in Roman mythology and religion. He is analogous with, but not identical to, the Greek god Poseidon. In the Greek-influenced tradition, Neptune was the brother of Jupiter and Pluto, each of them presiding over one of the three realms of the universe, Heaven, Earth and the Netherworld. Depictions of Neptune in Roman mosaics, especially those of North Africa, are influenced by Hellenistic conventions.[2]

Unlike the Greek Oceanus, titan of the world-ocean, Neptune was associated as well with fresh water. Georges Dumézil suggested[3] that for Latins, who were not a seafaring people, the primary identification of Neptune was with freshwater springs. Like Poseidon, Neptune was worshipped by the Romans also as a god of horses, under the name Neptunus Equester, a patron of horse-racing.[4]

Etymology

The etymology of Neptunus is unclear and disputed. The ancient grammarian Varro derived the name from nuptus i.e. covering (opertio), with a more or less explicit allusion to the nuptiae, marriage of Heaven and Earth.[5]

Among modern scholars P. Kretschmer proposed a derivation from IE *neptu-, moist substance.[6] Similarly R. Bloch supposed it might be an adjectival form in -no from *nuptu-, meaning "he who is moist".[7] Dumézil though remarked words deriving from root *nep are not attested in IE languages other than Vedic and Avestan. He proposed an etymology that brings together Neptunus with Vedic and Avestan theonyms Apam Napat, Apam Napá and Old Irish theonym Nechtan, all meaning descendant of the waters. By using the comparative approach the Indo-Iranian, Avestan and Irish figures would show common features with the Roman historicised legends about Neptune. Dumézil thence proposed to derive the nouns from IE root *nepot or *nept, descendant, siter's son.[8][9]

More recently, in his lectures delivered on various occasions in the late years of the last century, German scholar H. Petersmann proposed an etymology from IE rootstem *nebh related to clouds and foggs, plus suffix -tu denoting an abstract verbal noun, and adjectival suffix -no which refers to the domain of activity of a person or his prerogatives. IE root *nebh, having the original meaning of damp, wet, has given Sanskrit nábhah, Hittite nepis, Latin nubs, nebula, German nebel, Slavic nebo etc. The concept would be close to that expressed in the name of Greek god Όυράνος, derived from IE root *h2vórso-, to water, irrigate and *h2vorsó, the irrigator.[10][11] This etymology would be more in accord with Varro's.

A different etymology grounded in the legendary history of Latium and Etruria was proposed by Preller and Müller-Deeke: Etruscan Nethunus, Nethuns would be an adjectival form of toponym Nepe(t), Nepete (presently Nepi), town of the ager Faliscus near Falerii. The district was traditionally connected to the cult of the god: Messapus and Halesus, eponymous hero of Falerii, were believed to be his own sons. Messapus led the Falisci and others to war in the Aeneid.[12] Nepi and Falerii have been famed since antiquity for the excellent quality of the water of their springs, scattered in meadows.

Worship and theology

The theology of Neptune may only be reconstructed to some extent as since very early times he was identified with the Greek god Poseidon, as he is present already in the lectisternium of 399 BC.[13] Such an identification may well be grounded in the strict relationship between the Latin and Greek theologies of the two deities.[14] It has been argued that Indo-European people, having no direct knowledge of the sea as they originated from inland areas, reused the theology of a deity originally either chthonic or wielding power over inland freshwaters as the god of the sea.[15] This feature has been preserved particularly well in the case of Neptune who was definitely a god of springs, lakes and rivers before becoming also a god of the sea, as is testified by the numerous findings of inscriptions mentioning him in the proximity of such locations. Servius the grammarian also explicitly states Neptune is in charge of all the rivers, springs and waters.[16]

He may find a parallel in Irish god Nechtan, master of the well from which all the rivers of the world flow out and flow back to.

Poseidon on the other hand underwent the process of becoming the main god of the sea at a much earlier time, as is shown in the Iliad.[17]

In the earlier times it was the god Portunes or Fortunus who was thanked for naval victories, but Neptune supplanted him in this role by at least the first century BC when Sextus Pompeius called himself "son of Neptune."[18] For a time he was paired with Salacia, the goddess of the salt water.[19]

Neptune was also considered the legendary progenitor god of a Latin stock, the Faliscans, who called themselves Neptunia proles. In this respect he was the equivalent of Mars, Janus, Saturn and even Jupiter among Latin tribes. Salacia would represent the virile force of Neptune.[20]

The Neptunalia

The Neptunalia was the festival of Neptune on July 23, at the height of summer. The date and the construction of tree-branch shelters[21] suggest a primitive role for Neptune as god of water sources in the summer's drought and heat.[22]

The most ancient Roman calendar set the feriae of Neptunus on July 23, two days after the Lucaria of July 19 and 21 and two days before the Furrinalia of July 25. G. Wissowa had already remarked that festivals falling in a range of three days are related to each other. Dumezil elaborated that these festivals were all in some way related to the importance of the function of water during the period of summer heat (canicula), when river and spring waters are at their lowest. Founding his analysis on the works of Palladius and Columella Dumezil argues that while the Lucaria were devoted to the dressing of woods, clearing the undergrown bushes by cutting on the 19 and then by uprooting on the 21, (and burning them afterwards), the Neptunalia were spent in outings under branch huts (umbrae, casae frondeae), in a wood between the Tiber and the Via Salaria, drinking springwater and wine to escape the heat. It looks as though this festival was a time of general free and unrestrained merrymaking during which men and women mixed without the usual Roman traditional social constraints.[23] This character of the festival as well as the fact that Neptune was offered the sacrifice of a bull would point to an agricultural fertility context.[24]

The Furrinalia too, devoted to Furrina, a goddess of springs, were referred to those springs which had to be detected by drilling, i.e. required the work of man thence creating a correspondence with the Lucaria of 21, equally entailing an analogous human action upon the soil. The Furrinalia of July 25 are explained by Dumezil with the hydraulic works again as prescribed by Palladius, i.e. the drilling of wells to detect underground water: patent and hidden waters are thus dealt with on separate though next occasions.

===Temples===MADISON WOOOD WAZZ HEREERER.Neptune had two temples in Rome. The first, built in 25 BC, stood near the Circus Flaminius, the Roman racetrack, and contained a famous sculpture of a marine group by Scopas.[25] The second, the Basilica Neptuni, was built on the Campus Martius and dedicated by Agrippa in honour of the naval victory of Actium.[26]

Sacrifices

Neptune is one of only three Roman gods to whom it was appropriate to offer the sacrifice of bulls, the other two being Apollo and Mars.[27] The wrong offering would require a piaculum if due to inadvertency or necessity. The type of the offering implies a stricter connection between the deity and the worldly realm.[28]

Lake Albanus

The overflowing of Lake Albanus happened on the date of the Neptunalia. This prodigy that foretold the fall of Veii is a historical event that Dumezil ascribed to the Roman habit of projecting legendary heritage onto their own history. Livy relates that a haruspex from Veii who had been taken prisoner inadvertently gave away the prophecy that Veii would fall if the waters of the lake should overflow in the inland direction. On the contrary the fact would go to the disadvantage of Rome if the waters were to overflow towards the sea. The prophecy was confirmed by the oracle of Delphi consulted by the Roman senate.

This legend would show the scope of the powers hidden in waters and the religious importance of their control: Veientans knowing the fact had been digging channels for a long time as recent archaeological finds confirm. There is a temporal coincidence between the conjuration of the prodigy and the works of derivation recommended by Palladius and Columella at the time of the canicula, when the waters are at their lowest.

Paredrae

Paredrae are entities who pair or accompany a god. They represent the fundamental aspects or the powers of the god with whom they are associated. In Roman religion they are often female. In later times under Hellenising influence they came to be considered as separate deities and consorts of the god.[29] However this misconception might have been widespread in earlier folk belief.[30] In the view of Dumézil,[31] Neptune's two paredrae Salacia and Venilia represent the overpowering and the tranquil aspects of water, both natural and domesticated: Salacia would impersonate the gushing, overbearing waters and Venilia the still or quietly flowing waters.[32]

Salacia and Venilia have been the object of the attention of scholars both ancient and modern. Varro connects the first to salum, sea, and the second to ventus, wind.[33] Festus writes of Salacia that she is the deity that generates the motion of the sea.[34] While Venilia would cause the waves to come to the shore Salacia would cause their retreating towards the high sea.[35] The issue has been discussed in many passages by Christian doctor Aurelius Augustinus. He devotes one full chapter of his De Civitate Dei to mocking the inconsistencies inherent in the theological definition of the two entitites: since Salacia would denote the nether part of the sea, he wonders how could it be possible that she be also the retreating waves (Venilia being the waves that come to the shore), as waves are obviously a phenomenon of the surface of the sea.[36] Elsewhere he writes that Venilia would be the "hope that comes", one of the aspects or powers of the all encompassing Jupiter understood as the anima mundi.[37]

Servius in his commentary to the Aeneid also writes about Salacia and Venilia in various passages, e.g. V 724: "(Venus) dicitur et Salacia, quae proprie meretricum dea appellata est a veteribus": "(Venus) is also called Salacia, who precisely was named goddess of mercenary women by the ancient". Elsewhere he writes that Salacia and Venilia are indeed the same entity.[38]

Among modern scholars Dumézil with his followers Bloch and Schilling centre their interpretation of Neptune on the more direct, concrete, limited value and functions of water. Accordingly Salacia would represent the forceful and violent aspect of gushing and overflowing water, Venilia the tranquil, gentle aspect of still or slowly flowing water.

Preller, Fowler, Petersmann and Takács attribue to the theology of Neptune broader significance as a god of universal worldly fertility, particularly relevant to agriculture and human reproduction. Thence they interpret Salacia as personifying lust and Venilia as related to venia, the attitude of ingraciating, attraction, connected with love and desire for reproduction. L. Preller remarked a significant aspect of Venilia mentioning that she was recorded in the indigitamenta also as a deity of longing, desire. He thinks this fact would allow to explain the theonym in the same way as that of Venus.[39] Other data seem to point in the same direction: Salacia would be the parallel of Thetis as the mother of Achilles, while Venilia would be the mother of Turnus and Iuturna, whom she mothered with Daunus king of the Rutulians. According to another source Venilia would be the wife of Janus with whom she mothered the nymph Canens loved by Picus.[40] These mythical data underline the reproductive function envisaged in the figures of Neptune's paredrae, particularly that of Venilia in childbirth and motherhood. A legendary king Venulus was remembered at Tibur and Lavinium.[41]

Fertility deity and divine ancestor

German scholar H. Petersmann has proposed a rather different interpretation of the theology of Neptune. Developing his understanding of the theonym as rooted in IE *nebh, he argues that the god would be an ancient deity of the cloudy and rainy sky in company with and in opposition to Zeus/Jupiter, god of the clear bright sky. Similar to Caelus, he would be the father of all living beings on Earth through the fertilising power of rainwater. This hieros gamos of Neptune and Earth would be reflected in literarature, e.g. in Vergil Aen. V 14 pater Neptunus. The virile potency of Neptune would be represented by Salacia (derived from salax, salio in its original sense of salacious, lustful, desiring sexual intercourse, covering). Salacia would then represent the god's desire for intercourse with Earth, his virile generating potency manifesting itself in rainfall. While Salacia would denote the overcast sky, the other character of the god would be reflected by his other paredra Venilia, representing the clear sky dotted with clouds of good weather. The theonym Venilia would be rooted in a not attested adjective *venilis, from IE root *ven(h) meaning to love, desire, realised in Sanskrit vánati, vanóti, he loves, Old Island. vinr friend, German Wonne, Latin Venus, venia. Reminiscences of this double aspect of Neptune would be found in Catullus 31. 3: "uterque Neptunus".[42]

In Petersmann's conjecture, besides Zeus/Jupiter, (rooted in IE *dei(h) to shine, who originally represented the bright daylight of fine weather sky), the ancient Indo-Europeans venerated a god of heavenly damp or wet as the generator of life. This fact would be testified by Hittite theonyms nepišaš (D)IŠKURaš or nepišaš (D)Tarhunnaš "the lord of sky wet", that was revered as the sovereign of Earth and men.[43] Even though over time this function was transferred to Zeus/Jupiter who became also the sovereign of weather, reminiscences of the old function survived in literature: e.g. in Vergil Aen. V 13-14 reading: "Heu, quianam tanti cinxerunt aethera nimbi?/ quidve, pater Neptune, paras?": "Whow, why so many clouds surrounded the sky? What are you preparing, father Neptune?".[44] The indispensability of water for its fertilizing quality and its strict connexion to reproduction is universal knowledge.[45] Takács too points to the implicit sexual and fertility significance of both Salacia and Venilia on the grounds of the context of the cults of Neptune, of Varro's interpretation of Salacia as eager for sexual intercourse and of the connexion of Venilia with a nymph or Venus.

Müller-Deeke and Deeke had already interpreted the theology of Neptune as that of a divine ancestor of a Latin stock, namely the Faliscans, as the father of their founder heroes Messapus and Halesus. Sharing this same approach Fowler considered Salacia the personification of the virile potency that generated a Latin people, parallel with Mars, Saturn, Janus and even Jupiter among other Latins.[46]

Neptunus equestris

Poseidon was connected to the horse since the earliest times, well before any connection of him with the sea was attested, and may even have originally been conceived under equine form. Such a feature is a reflection of his own chtonic, violent, brutal nature as earth-quaker, as well as of the link of the horse with springs, i.e. underground water, and the psychopompous character inherent in this animal.[47]

There is no such direct connexion in Rome. Neptune does not show any direct equine character or linkage.

It was Roman god Consus who bore a connexion to horses: his underground altar was located in the valley of the Circus Maximus at the foot of the Palatine, the place of horse races. On the day of his summer festival (August 21), the Consualia aestiva, it was customary to bring in procession horses and mules crowned with flowers and then hold equine races in the Circus. It appears these games had a rustic character: they marked the end of the yearly agricultural cycle, when harvest was completed.[48] According to tradition this occasion was chosen to enact the abduction of the Sabine (and Latin) women. The episode might bear a reflection of the traditional sexual licence of such occasions.[49] On that day the flamen Quirinalis and the vestal virgins sacrificed on the underground altar of Consus. The fact the two festivals of Consus were followed after an equal interval of four days by the two festivals of Ops (Opeconsivia on August 25 and Opalia on December 19) testifies to the strict relationship between the two deities as pertaining to agricultural bounty, or in Dumezilian terminology to the third function. This fact shows the radically different symbolic value of the horse in the theology of Poseidon and that of Consus.

Perhaps under the influence of Poseidon Ίππιος Consus was reinterpreted as Neptunus equestris and for his underground altar also identified with Poseidon Ένοσίχθων. The archaic and arcane character of his cult, which required the unearthing of the altar, are signs of the great antiquity of this deity and of his chtonic character. He was certainly a deity of agrarian plenty and of fertility. Dumezil interprets its name as derived from condere hide, store as a verbal noun in -u parallel to Sancus and Janus, meaning god of stored grains.[50]

Martianus Capella places Neptune and Consus together in region X of Heaven: it might be that he followed an already old interpretatio graeca of Consus or he might be reflecting an Etruscan idea of a chthonic Neptune. Etruscans were particularly fond of horse races.[51]

Neptune in Etruria

Nethuns is the Etruscan name of the god. In the past it has been believed that the Roman theonym derived from Etruscan but more recently this view has been rejected.[citation needed]

Nethuns was certainly an important god for the Etruscans. His name is to be found on two cases of the Piacenza Liver, namely case 7 on the outer rim and case 28 on the gall-bladder, (plus once in case 22 along with Tinia). This last location tallies with Pliny the Elder's testimony that the gall-bladder is sacred to Neptune.[52] Theonym Nethuns recurs eight times on columns VIII, IX and XI of the Liber Linteus (flere, flerchva Nethunsl), requiring offerings of wine.[53]

On a mirror from Tuscania (E. S. 1. 76) Nethuns is represented while talking to Uśil (the Sun) and Thesan (the goddess of Dawn). Nethuns is on the left hand side, sitting, holding a double ended trident in his right hand and with his left arm raised in the attitude of giving instructions, Uśil is standing at the centre of the picture, holding in his right hand Aplu's bow, and Thesan is on the right, with her right hand on Uśil's shoulder: both gods look intent in listening Nethuns's words. The identification of Uśil with Aplu (and his association with Nethuns) is further underlined by the anguiped demon holding two dolphins of the exergue below. The scene highlights the identities and association of Nethuns and Aplu (here identified as Uśil) as main deities of the worldly realm and the life cycle. Thesan and Uśil-Aplu, who has been identified with Śuri (Soranus Pater, the underwold Sun god) make clear the transient character of worldly life.[54] The association of Nethuns and Uśil-Aplu is consistent with one version of the theory of the Etruscan Penates (see section below).

In Martianus Capella's depiction of Heaven Neptune is located in region X along with the Lar Omnium Cunctalis (of everybody), Neverita and Consus. The presence of the Lar Omnium Cunctalis might be connected with the theology of Neptune as a god of fertility, human included, while Neverita is a theonym derived from an archaic form of Nereus and Nereid, before the fall of the digamma.[55] For the relationship of Neptune with Consus see the above paragraph. Martianus's placing of Neptune is fraught with questions: according to the order of the main three gods he should be located in region II, (Jupiter is indeed in region I and Pluto in region III). However in region II are to be found two deities related to Neptune, namely Fons and Lymphae. Stephen Weinstock supposes that while Jupiter is present in each of the first three regions, in each one under different aspects related to the character of the region itself, Neptune should have been originally located in the second, as is testified by the presence of Fons and Lymphae, and Pluto in the third. The reason of the displacement of Neptune to region X remains unclear, but might point to a second appearance of the triads in the third quarter, which is paralleled by the location of Neth in case 7 of the Liver.[56] It is however consistent with the collocation in the third quadrant of the deities directly related to the human world.[57]

Bloch remarks the possible chtonic character and stricter link of Nethuns with Poseidon to which would hint a series of circumstances, particularly the fact that he was among the four gods (Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Tellus in order) the haruspices indicated as needing placation for the prodigy related in Cicero's De haruspicum responso 20, i.e. a cracking sound perceived as coming from the underground in the ager latiniensis.

Neptune and the Etruscan Penates

Among ancient sources Arnobius provides important information about the theology of Neptune: he writes that according to Nigidius Figulus Neptune was considered one of the Etruscan Penates, together with Apollo, the two deities being credited with bestowing on Ilium its immortal walls. In another place of his work, book VI, Nigidius wrote that, according to the Etrusca Disciplina, his were one among the four genera, types of Penates: of Iupiter, of Neptune, of the underworld and of mortal men. According to another tradition related by a Caesius,[58] also based on the same source, the Etruscan Penates would be Fortuna, Ceres, Genius Iovialis and Pales, this last one being the male Etruscan god (ministrum Iovis et vilicum, domestic and peasant of Jupiter).[59]

Depiction in art

Antiquity

The French Department of Subaquatic Archaeological Research divers (headed by Michel L'Hour) discovered a lifesize marble statue of Neptune, in the Rhone River at Arles; it is dated to the early fourth century.[60] The statue is one of a hundred artifacts that the team excavated between September and October 2007.[60][61]

Etruscan representations of the god are rare but significative. The oldest is perhaps the carved carnelian scarab from Vulci of the 4th century BC: Nethuns kicks a rock and creates a spring. (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale, Cabinet des Medailles).

Another Etruscan gem (from the collection of Luynes, inscribed Nethunus) depicts the god making a horse spring out of the earth with a blow of his trident. [62]

A bronze mirror of the late 4th century in the Vatican Museums (Museo Gregoriano Etrusco: C.S.E. Vaticano 1.5a) depicting the god with Amymone, daughter of Danaus, whom he prevents being assaulted by a satyr and to whom he will teach the art of creating springs. Nearby are a lion head pouring water from its open mouth and a container with handles.

A bronze mirror from Tuscania dated to 350 BC also in the Vatican Museums (Museo Gregoriano Etrusco E. S. 1. 76). Nethuns is talking to Usil and Thesan. In the lower exergue is an anguiped demon who holds a dolphin in each hand (identification with Aplu-Apollo is clear also because Uśil holds a bow). Nethuns holds a double-ended trident, suggesting he might be one of the gods who can wield lightningbolts.[63]

Renaissance

The Renaissance brought with it a revival in pagan art, and many pagan gods were depicted in the same classical models used in Greek and Roman times. However, with Neptune few such models existed, allowing the artists of the Renaissance to depict Neptune however they chose. The results included a face and actions that seemed more mortal, as well as associations with Hercules. The overall effect was to change Neptune's image to a less deified state.[64]

Gallery

-

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Andrea Doria as Neptune (1540-1550)

-

Giovan Battista Tiepolo, Neptune Offering Gifts to Venice (1748-1750)

-

Juan Pascual de Mena, Fuente de Neptuno, Madrid (1780–1784)

-

Neptune, tobacco product art (1860-1870)

-

King Neptune (2005), Virginia Beach, Virginia

Modern culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2011) |

"King Neptune" plays a central role in the long-standing tradition of the "Line-crossing ceremony" initiation rite still current in many navies, coast guards, and merchant fleets. When ships cross the equator, "Pollywogs" (sailors who have not done such a crossing before) receive "subpoenas"[65] to appear before King Neptune and his court (usually including his first assistant Davy Jones and Her Highness Amphitrite and often various dignitaries, who are all represented by the highest-ranking seamen). Some Pollywogs may be "interrogated" by King Nepture and his entourage. At the end of the ceremony — which in the past often included considerable hazing — they are initiated as Shellbacks or Sons of Neptune and receive a certificate to that effect.

References and notes

- ^ J. Toutain, Les cultes païens de l'Empire romain, vol. I (1905:378) securely identified Italic Neptune as a god of freshwater sources as well as the sea.

- ^ Alain Cadotte, "Neptune Africain", Phoenix 56.3/4 (Autumn/Winter 2002:330-347) detected syncretic traces of a Lybian/Punic agrarian god of fresh water sources, with the epithet Frugifer, "fruit-bearer"; Cadotte enumerated (p.332) some north African Roman mosaics of the fully characteristic Triumph of Neptune, whether riding in his chariot or mounted directly on sea-beasts.

- ^ Dumézil, La religion romaine archaïque (Paris, 1966:381)

- ^ Compare Epona.

- ^ Varro Lingua Latina V 72: Neptunus, quod mare terras obnubuit ut nubes caelum, ab nuptu, id est opertione, ut antiqui, a quo nuptiae, nuptus dictus.: "N., because the sea covered the lands as the clouds the sky, from nuptus i.e. covering, as the ancients (used to say), whence nuptiae marriage, was named nuptus".

- ^ P. Kretschmer Einleitung in der Geschichte der Griechischen Sprache Göttingen, 1896, p. 33

- ^ R. Bloch "Quelques remarques sur Poseidon, Neptunus et Nethuns" in Revue de l' Histoire des Religions 1981, p. 347

- ^ Y. Bonnefoy, W. Doniger Roman and Indoeuropean Myhtologies Chicago, 1992, s.v. Neptune, citing G. Dumezil Myht et Epopée vol. III p. 41 and Alfred Ernout- Atoine Meillet Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine Paris, 1985 4th, s.v. Neptunus.

- ^ G. Dumézil Fêtes romaines d' étè et d' automne, suivi par dix questions romaines Paris 1975, p.25.

- ^ H. Petersmann below, Göttingen 2002

- ^ M. Peters "Untersuchungen zur Vertratung der indogermanischen Laryngeale in Griechisch" in Österreicher Akademie der Wissenschaften, philsophische historische Klasse Bd. 372, 1980 p.180

- ^ Vergil Aen. VII 691: L. Preller Römische Mythologie II Berlin, 1858; Müller-Deeke Etrusker II 54 n. 1b; Deeke Falisker p. 103, as quoted by William Warde Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London, 1899, p. 185 and n. 3

- ^ Livy v. 13.6; Dionysius of Halicarnassus 12.9; Showerman, Grant. The Great Mother of the Gods. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1901:223

- ^ Raymond Bloch "Quelques remarques sur Poseidon, Neptunus and Nethuns" in Revue de l'Histoire des Religions 1981 p.341-352

- ^ G. Wissowa Religion un Kultus der Römer Munich, 1912; A. von Domaszewski Abhandlungen zur römische Religion Leipzig und Berlin, 1909; R. Bloch above

- ^ Bloch above p.346; Servius Ad Georgicae IV 24

- ^ R. Bloch above

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane. The Classical World. Basic Books, 2006. p. 412 ISBN 0465024963

- ^ van Aken, Dr. A.R.A., ed. Elseviers Mythologische Encyclopedie (Elsevier, Amsterdam: 1961)

- ^ W. W. Fowler above p. 186 n. 3 citing Servius Ad Aen. V 724; later Doctor Fowler disowned this interpretation of Salacia.

- ^ CIL, vol. 1,pt 2:323; Varro, De lingua latina vi.19.

- ^ "C'est-à-dire au plus fort de l'été, au moment de la grande sécheresse, et qu'on y construisaient des huttes de feuillage en guise d'abris contre le soleil" (Cadotte 2002:342, noting Sextus Pompeius Festus, De verborum significatu [ed. Lindsay 1913] 519.1)

- ^ Sarolta A. Takacs Vestal virgins, sibyls and matronae: women in Roman religion 2008, University of Texas Press, p. 53 f., citing Horace Carmina III 28

- ^ Sarolta A. Takacs above; Macrobius Saturnalia III 10, 4

- ^ Wukitsch, Thomas K., Neptunalia Festival

- ^ Ball Platner, Samuel; Ashby, Thomas (1929), A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, "Basilica Neptuni", London: Oxford University Press

- ^ Macrobius Saturnalia III 10,4

- ^ G. Dumezil "Quaestiunculae indo-italicae: 11. Iovi tauro verre ariete immolari non licet" Revue d' Etudes Latins 39 1961 p. 241-250.

- ^ William Warde Fowler The Religious experience of the Roman People London, 1912, p. 346f.

- ^ Aulus Gellius Noctes Atticae XIII 24, 1-18.

- ^ Dumézil here accepts and reproposes the interpretations of Wissowa and von Domaszewski.

- ^ Dumezil above p.31

- ^ Varro Lingua Latina V 72

- ^ Festus p. L s.v.

- ^ Varro apud Augustine De Civitate Dei VII 22

- ^ Augustine De Civitate Dei VII 22.

- ^ Augustine above II 11.

- ^ William Warde Fowler The Religious Experience of the Roman People London, 1912, Appendix II.

- ^ Ludwig Preller Römische Mythologie Berlin, 1858 part II, p.121-2; Servius Ad Aen. VIII 9.

- ^ Ovid Metam. XIV 334.

- ^ L. Preller above citing Servius; C. J. Mackie "Turnus and his ancestors" in The Classical Quarterly (New Series) 1991, 41, pp. 261-265.

- ^ Catullus 31. 3: "Paene insularum, Sirmio, insularumque/ ocelle , quascumque in liquentibus stagnis/ marique vasto fert uterque Neptunus/...": the quoted words belong to a passage in which the poet seems to be hinting to the double nature of Neptune as god both of the freshwaters and of the sea.

- ^ Eric Neun Die Anitta-Text Wiesbaden, 1974, p. 118

- ^ H. Petersmann "Neptuns ürsprugliche Rolle im römischen Pantheon. Ein etymologisch-religiongeschichtlicher Erklärungsversuch" in Lingua et religio. Augewählte kleine Beiträge zur antike religiogeschichtlicher und sprachwissenschaftlicher Grundlage Göttingen, 2002, pp. 226-235

- ^ cf. Festus s. v. aqua: "a qua iuvamur", whence we get life, p 2 L.; s. v. aqua et igni : "...quam accipiuntur nuptae, videlicet quia hae duae res...vitam continent", p.2-3 L; s.v. facem: "facem in nuptiis in honore Cereris praeferebant, aqua aspergebatur nova nupta...ut ignem et aquam cum viro communicaret", p.87 L.

- ^ William Warde Fowler The roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London, 1899, p. 126

- ^ Raymond Bloch above p. 43

- ^ William Warde Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London, 1899, p.

- ^ William Warde Fowler above, citing James G. Frazer

- ^ Cf. the related deities of the Circus Semonia, Seia, Segetia, Tutilina: Tertullian De Spectaculis VIII 3

- ^ R. Bloch above ; G. Capdeville "Les dieux de Martianus Capella" in Revue de l'Histoire des Religions 213-3, 1996, p. 282 n. 112

- ^ R. Bloch above; Pliny Nat. Hist. XI 195

- ^ N. Thomas De Grummond Etruscam Myth, Sacred History and Legend Univ. of Pennsylvania Press 2006 p. 145

- ^ Erika Simon "Gods in Harmony: The Etruscan Pantheon" in N. Thomas De Grummond (editor) Etruscan Religion 2006 p. 48; G . Colonna "Altari e sacelli: l'area sud di Pyrgi dop otto anni di ricerche" Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia di Archeologia 64 p. 63-115; "Sacred Architecture and the Religion of the Etruscans" in N. Thomas DeGrummond above p.139

- ^ Ludwig Preller Römische Mythologie Berlin, 1858, II p. 1

- ^ G. Dumezil La religion romaine archaique Paris, 1974 2nd, Appendix; It. tr. p. 584; citing Stephen Weinstock "Martianus Capella and the Cosmic System of the Etruscans" in Journal of Roman Studies 36, 1946, p. 104 ff.; G. Capdeville "Les dieux de Martianus Capella" in Revue del'Histoire ded Reliogions 213-3, 1996, p. 280-281

- ^ Cf. M. Pallottino "Deorum sedes" in Saggi di antichitá. II. Documenti per la storia della civiltá etrusca Roma 1979 p. 779-790. For a summary exposition of the content of this work the reader is referred to article Juno, section Etrurian Uni note n. 201.

- ^ It is difficult to ascertain his identity.

- ^ Arnobius Adversus Nationes III 40, 1-2.

- ^ a b Divers find Caesar bust that may date to 46 B.C., Associated Press, 2008-05-14

- ^ Henry Samuel, "Julius Caesar bust found in Rhone River", The Telegraph

- ^ Jacques Heurgon in R. Bloch above p. 352.

- ^ N. Thomas De Grummond above p. 145.

- ^ Freedman, Luba (September 1995), "Neptune in classical and Renaissance visual art" (PDF), International Journal of the Classical Tradition, vol. 2, no. 2, Springer Netherlands, pp. 219–237, ISSN 1874-6292

- ^ Ceremonial Certificates — Neptune Subpoena

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

hi