New London School explosion

1937 newsreel | |

| Date | March 18, 1937 |

|---|---|

| Time | 3:05 – 3:20 p.m. Central Time |

| Location | New London, Texas |

| Deaths | 295+ |

| Non-fatal injuries | 300+ |

The New London School explosion occurred on March 18, 1937, when a natural gas leak caused an explosion, destroying the London School of New London, Texas,[1] a community in Rusk County previously known as "London". The disaster killed more than 295 students and teachers, making it the deadliest school disaster in American history. As of 2017[update], the event is the third deadliest disaster in the history of Texas, after the 1900 Galveston hurricane and the 1947 Texas City disaster.

Background

In the mid-1930s, the Great Depression was in full swing, but the London school district was one of the richest in America. A 1930 oil find in Rusk County had boosted the local economy and educational spending grew with it. The London School, a large structure of steel and concrete, was constructed in 1932 at a cost of $1 million (roughly $22.3 million today[2]). The London Wildcats (a play on the term "wildcatter", for an oil prospector) played football in the first stadium in the state to have electric lights.[citation needed]

The school was built on sloping ground and a large air space was enclosed beneath the structure. The school board had overridden the original architect's plans for a boiler and steam distribution system, instead opting to install 72 gas heaters throughout the building.[3]

Early in 1937, the school board canceled their natural gas contract and had plumbers install a tap into Parade Gasoline Company's residue gas line to save money. This practice—while not explicitly authorized by local oil companies—was widespread in the area. The natural gas extracted with the oil was considered a waste product and was flared off. As there was no value to the natural gas, the oil companies turned a blind eye. This "raw" or "wet" gas varied in quality from day to day, even from hour to hour.[4]

Untreated natural gas is both odorless and colorless, so leaks are difficult to detect and may go unnoticed. Gas had been leaking from the residue line tap and built up inside the enclosed crawlspace that ran the entire 253-foot (77 m) length of the building's facade. Students had been complaining of headaches for some time, but little attention had been paid to the issue.[5]

March 18 was a Thursday. Friday's classes were canceled to allow students to participate in the neighboring city of Henderson's Interscholastic Meet, a scholastic and athletic competition. Following the school's normal schedule, first through fourth grade students had been let out early. A PTA meeting was being held in the gymnasium, a separate structure roughly 100 feet (30 m) from the main building.

Explosion

At 3:17 p.m., Limmie R. Butler[6] (an "instructor of manual training") turned on an electric sander.[citation needed] It is believed that the sander's switch caused a spark that ignited the gas-air mixture.[citation needed]

Reports from witnesses state that the walls of the school bulged, the roof lifted from the building and then crashed back down, and the main wing of the structure collapsed. The force of the explosion was so great that a two-ton concrete block was thrown clear off the building and crushed a 1936 Chevrolet parked 200 feet away. Approximately 500 students and 40 teachers were in the building at the time.[7]

Reaction

The explosion was its own alarm, heard for miles. The most immediate response was from parents at the PTA meeting. Within minutes, area residents started to arrive and began digging through the rubble, many with their bare hands. Roughnecks from the oil fields were released from their jobs and brought with them cutting torches and heavy equipment needed to clear the concrete and steel.

School bus driver Lonnie Barber was transporting elementary students to their homes and was in sight of the school as it exploded. Barber continued his two-hour route, returning children to their parents before rushing back to the school to look for his four children. His son Arden died, but the others were not seriously injured.[8] Barber retired the next year.

Aid poured in from outside the area. Governor James Allred dispatched Texas Rangers, highway patrol, and the Texas National Guard. Thirty doctors, 100 nurses, and 25 embalmers arrived from Dallas. Airmen from Barksdale Field, deputy sheriffs, and even Boy Scouts took part in the rescue and recovery.

Of the more than 600 people in the school, only about 130 escaped without serious injury. Estimates of the number of dead vary from 296 to 319 but that number could be much higher as many of the residents of New London at the time were transient oilfield workers, and there is no way to determine how many volunteers collected the bodies of their children in the days following the disaster and returned them to their respective homes for burial. Most of the bodies were either burned beyond recognition,[citation needed] or blown to pieces. It was thought that one mother had a heart attack and died when she found out that her daughter died, with only part of her face, her chin and a couple of bones recovered, but this story was found to be untrue when both mother and daughter were found alive.[9] Another boy was identified by the presence of the pull string from his favorite shirt in his jeans pocket.

Rescuers worked through night and rain, and 17 hours later, the entire site had been cleared. Buildings in the neighboring communities of Henderson, Overton, Kilgore and as far away as Tyler and Longview were converted into makeshift morgues to house the enormous number of bodies, and everything from family cars to delivery trucks served as hearses and ambulances. A new hospital, Mother Frances Hospital in nearby Tyler, was scheduled to open the next day, but the dedication was canceled and the hospital opened immediately.[10]

Reporters who arrived in the city found themselves swept up in the rescue effort. Former Dallas Times Herald executive editor Felix McKnight, then a young AP reporter, recalled, "We identified ourselves and were immediately told that helpers were needed far more than reporters." Walter Cronkite also found himself in New London on one of his first assignments for UPI. Although Cronkite went on to cover World War II and the Nuremberg trials, he was quoted as saying decades later, "I did nothing in my studies nor in my life to prepare me for a story of the magnitude of that New London tragedy, nor has any story since that awful day equaled it."[11]

Not all of the buildings on the 10-acre (4.0 ha) campus were destroyed. The surviving gymnasium was quickly converted into multiple classrooms. Inside tents and modified buildings, classes resumed ten days later.

The majority of the victims of the explosion are buried at Pleasant Hill Cemetery, near New London.

Adolf Hitler, who was the German Chancellor at the time, paid his respects in the form of a telegram, a copy of which is on display at the London Museum.[12][13]

Aftermath

Experts from the United States Bureau of Mines concluded that the connection to the residue gas line was faulty. The connection had allowed gas to leak into the school, and since natural gas is invisible and is odorless, the leak was unnoticed. The sanding machine's switch is believed to have caused a spark that ignited the gas-air mixture. To reduce the damage of future leaks, the Texas Legislature began mandating within weeks of the explosion that thiols (mercaptans) be added to natural gas.[1] The strong odor of many thiols makes leaks quickly detectable. The practice quickly spread worldwide.

Shortly after the disaster, the Texas Legislature met in emergency session and enacted the Engineering Registration Act (now rewritten as the Texas Engineering Practice Act). Public pressure was on the government to regulate the practice of engineering due to the faulty installation of the natural gas connection; Carolyn Jones, a nine-year-old survivor, spoke to the Texas Legislature about the importance of safety in schools.[14] The use of the title "engineer" in Texas remains legally restricted to those who have been professionally certified by the state to practice engineering.[14]

A lawsuit was brought against the school district and the Parade Gasoline Company, but the court ruled that neither could be held responsible. Superintendent W. C. Shaw was forced to resign amid talk of a lynching. Shaw lost a son, a nephew and his niece in the explosion [15]

A new school was completed in 1939 on the property, directly behind the location of the destroyed building. The school remained known as the London School until 1965 when London Independent School District consolidated with Gaston Independent School District, the name was changed to West Rusk High School, and the mascot was changed to the Raiders.

Remembrance

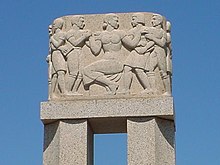

A large granite cenotaph on the median of Texas State Highway 42 across from the school site, erected in 1939, commemorates the disaster.

Over the years, the New London School explosion received relatively little attention, given the magnitude of the event. Explanations for this are speculative, but most center around residents' unwillingness to discuss the tragedy. L. V. Barber said of his father Lonnie, "I can remember newspaper people coming around every now and then, asking him questions about that day, but he never had much to say." Nevertheless, in recent years, as the disaster has gained historical perspective, it has been increasingly covered by researchers and journalists.

In 1973, Texas filmmaker Michael Brown produced a half-hour documentary on the explosion thought to be the first ever made on the subject. Called New London: The Day the Clock Stood Still, the film features survivors of the blast and their recollections of that day.

The 50th anniversary of the event, in 1987, was commemorated in part by the release of a documentary, "The Day A Generation Died", written, produced, and directed by Jerry Gumbert.[16]

In 1998, The London Museum and Tea House, across the highway from the school site, opened. Its first curator Mollie Ward, was an explosion survivor.

In 2007, the Texas-based folk band JamisonPriest released "Lost Generation (The New London Song)" to commemorate this event.[17]

In 2008, some of the last living survivors of the explosion shared their personal stories of their experience with documentary filmmaker and East Texas native, Kristin Beauchamp. The feature-length documentary, When Even Angels Wept, was released in 2009 and was a first-hand account of the disaster. It is told almost exclusively by survivors and eyewitnesses. They share what they experienced on the afternoon leading up to the blast to what it was like to spend days searching East Texas towns, hospitals and morgues for missing loved ones.

A one act play about the event, written by Dr. Bobby H. Johnson, a journalist and Professor Emeritus of history at Stephen F. Austin State University, called A Texas Tragedy,[18] has been performed by students at Huntington High School in Huntington and in other regional venues.

In March 2012, survivors and others gathered together at the town's rebuilt school in remembrance of the 75th anniversary of the disaster.[19]

In 2012, Texas filmmaker Michael Brown began work on a new documentary about the east Texas oil field discovery and its eventual role in the New London School disaster. The film, scheduled for completion by spring of 2013 and carrying a working title of Shadow Across The Path, features excerpts from an hour-long interview that Brown conducted with Walter Cronkite in his New York office at CBS. The interview has never been seen or published. The New London school explosion was then-20-year-old Cronkite's first national story. The new work will also feature recent interviews with blast survivors.[citation needed]

In 2012, the book Gone at 3:17: The Untold Story of the Worst School Disaster in American History, by journalists David M. Brown and Michael Wereschagin, was published by Potomac Books. Also in 2012, Ron Rozelle, a member of the Texas Institute of Letters, wrote a book about the tragedy called My Boys and Girls are in There. The book was released to coincide with the seventy-fifth anniversary of the disaster.[20]

The 2015 historical novel Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez depicts the explosion incident.[21]

See also

- List of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions

- Our Lady of the Angels School Fire

- Collinwood School Fire

- Bath School Disaster

References

- ^ a b Texas State Historical Commission. "New London School Explosion". StoppingPoints.com.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "The London Museum on the Web!". Archived from the original on January 8, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ Cornell, James C. (1983), The Great International Disaster Book (3rd ed.), Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ "Robertson, William". September 28, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "Limmie Raines Butler". Find a Grave. Retrieved March 15, 2016. Grave marker has his first name spelled as Limmie.

- ^ JR., MAY, IRVIN M., (June 15, 2010). "NEW LONDON SCHOOL EXPLOSION". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "RootsWeb.com Home Page". freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Gone at 3:17: The Untold Story of the Worst School Disaster in American History Kindle Edition, David Brown and Michael Wereschagin

- ^ http://www.tmfhs.org/history.php

- ^ "Cronkite, Walter". April 23, 2008. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Per the History Channel's Modern Marvels series

- ^ "East Texas & Cane River Ride / 2008 Apr 10 323.jpg". Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "Texas Board of Professional Engineers: An Inventory of Board of Professional Engineers Records at the Texas State Archives, 1937, 1952, 1972-2001, 2005-2006, undated". www.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1937/03/20/118967356.pdf

- ^ "List of Documentaries about the Tragedy". Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ http://www.jamisonpriest.com/

- ^ Johnson, Bobby H.(2012), A Texas Tragedy. Stephen F. Austin University Press

- ^ Allan Turner (March 11, 2012), Memories still vivid 75 years after school explosion, Houston Chronicle

- ^ "My Boys and Girls Are in There — The 1937 New London School Explosion". Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ "OUT OF DARKNESS" (Archive). Kirkus Reviews. June 1, 2015. Review posted online May 6, 2015. Retrieved on November 8, 2015.

External links

- New London School Explosion from the Handbook of Texas Online

- New London School Explosion webpage from the New London Museum

- 'New London Holds Explosion Reunion' – KLTV/7 report, March 18, 2007

- '70th Anniversary of New London School Explosion' (KETK/56 report, March 18, 2007)

- Universal Newsreel footage 'special release'