Numerical weather prediction

Numerical weather prediction uses current weather conditions as input into mathematical models of the atmosphere to predict the weather. Although the first efforts to accomplish this were done in the 1920s, it wasn't until the advent of the computer and computer simulation that it was feasible to do in real-time. Manipulating the huge datasets and performing the complex calculations necessary to do this on a resolution fine enough to make the results useful requires the use of some of the most powerful supercomputers in the world. A number of forecast models, both global and regional in scale, are run to help create forecasts for nations worldwide. Use of model ensemble forecasts helps to define the forecast uncertainty and extend weather forecasting farther into the future than would otherwise be possible.

Physical overview

The atmosphere is a fluid. The basic idea of numerical weather prediction is to sample the state of the fluid at a given time and use the equations of fluid dynamics and thermodynamics to estimate the state of the fluid at some time in the future.

History

British mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson first proposed numerical weather prediction in 1922. Richardson attempted to perform a numerical forecast but it was not successful. The first successful numerical prediction was performed in 1950 by a team composed of the American meteorologists Jule Charney, Philip Thompson, Larry Gates, and Norwegian meteorologist Ragnar Fjörtoft and applied mathematician John von Neumann, using the ENIAC digital computer. They used a simplified form of atmospheric dynamics based on the barotropic vorticity equation. This simplification greatly reduced demands on computer time and memory, so that the computations could be performed on the relatively primitive computers available at the time. Later models used more complete equations for atmospheric dynamics and thermodynamics.

Operational numerical weather prediction (i.e., routine predictions for practical use) began in 1955 under a joint project by the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Weather Bureau.[1]

Definition of a forecast model

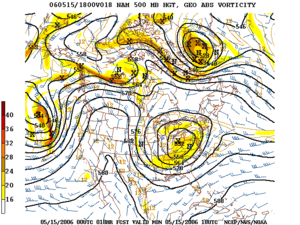

A model, in this context, is a computer program that produces meteorological information for future times at given positions and altitudes. The horizontal domain of a model is either global, covering the entire Earth, or regional , covering only part of the Earth. Regional models also are known as limited-area models.

The forecasts are computed using mathematical equations for the physics and dynamics of the atmosphere. These equations are nonlinear and are impossible to solve exactly. Therefore, numerical methods obtain approximate solutions. Different models use different solution methods. Some global models use spectral methods for the horizontal dimensions and finite difference methods for the vertical dimension, while regional models and other global models usually use finite-difference methods in all three dimensions. Regional models also can use finer grids to explicitly resolve smaller-scale meteorological phenomena, since they do not have to solve equations for the whole globe.

Models are initialized using observed data from radiosondes, weather satellites, and surface weather observations. The irregularly-spaced observations are processed by data assimilation and objective analysis methods, which perform quality control and obtain values at locations usable by the model's mathematical algorithms (usually an evenly-spaced grid). The data are then used in the model as the starting point for a forecast. Commonly, the set of equations used is known as the primitive equations. These equations are initialized from the analysis data and rates of change are determined. The rates of change predict the state of the atmosphere a short time into the future. The equations are then applied to this new atmospheric state to find new rates of change, and these new rates of change predict the atmosphere at a yet further time into the future. This time stepping procedure is continually repeated until the solution reaches the desired forecast time. The length of the time step is related to the distance between the points on the computational grid. Time steps for global climate models may be on the order of tens of minutes, while time steps for regional models may be a few seconds to a few minutes.

Ensembles

As proposed by Edward Lorenz in 1963, it is impossible to definitively predict the state of the atmosphere, owing to the chaotic nature of the fluid dynamics equations involved. Furthermore, existing observation networks have limited spatial and temporal resolution, especially over large bodies of water such as the Pacific Ocean, which introduces uncertainty into the true initial state of the atmosphere. To account for this uncertainty, stochastic or "ensemble" forecasting is used, involving multiple forecasts created with different model systems, different physical parametrizations, or varying initial conditions. The ensemble forecast is usually evaluated in terms of the ensemble mean of a forecast variable, and the ensemble spread, which represents the degree of agreement between various forecasts in the ensemble system, known as ensemble members. A common misconception is that low spread amongst ensemble members necessarily implies more confidence in the ensemble mean. Although a spread-skill relationship sometimes exists, the relationship between ensemble spread and skill varies substantially depending on such factors as the forecast model and the region for which the forecast is made.

See also

- Tropical cyclone forecast model

- Atmospheric physics

- Atmospheric thermodynamics

- Frederick Gale Shuman

- André Robert

- the Unified Model and the Weather Research and Forecasting model -- two numerical weather prediction software suites used by weather agencies around the world

References

- ^ American Institute of Physics. Atmospheric General Circulation Modeling. Retrieved on 2008-01-13.

Further reading

- Beniston, Martin. From Turbulence to Climate: Numerical Investigations of the Atmosphere with a Hierarchy of Models. Berlin: Springer, 1998.

- Kalnay, Eugenia. Atmospheric Modeling, Data Assimilation and Predictability. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Thompson, Philip. Numerical Weather Analysis and Prediction. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1961.

- Pielke, Roger A. Mesoscale Meteorological Modeling. Orlando: Academic Press, Inc., 1984.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service. National Weather Service Handbook No. 1 - Facsimile Products. Washington, DC: Department of Commerce, 1979.

External links

- PredictWind World wide weather model offering High Resolution Wind Forecasting

- Description of models used in the United States circa 1995

- meteoblue - free maps and diagrams of NWP (high resolution NMM and GFS) data worldwide

- NOAA Supercomputers

- Wetterzentrale (German only) - nearly all NWP data available plotted on charts

- Air Resources Laboratory

- Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

- University of Reading Department of Meteorology

- WRF Source Codes and Graphics Software Download Page

- RAMS source code available under the GNU General Public License

- MM5 Source Code download

- The source code of ARPS

- ALADIN Community web pages