Nuna

| solar racer |

| Nuna |

|---|

Nuna is the name of a series of manned solar powered race cars that won the World solar challenge in Australia six times, of which four times in a row: in 2001 (Nuna 1 or just Nuna), 2003 (Nuna 2), 2005 (Nuna 3), 2007 (Nuna 4), 2013 (Nuna 7) and 2015 (Nuna 8). The Nunas are built by students who are part of the Nuon Solar Team at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

"Nuna" is also the Icelandic word "now."

Nuna

Design criteria

To have a good chance to win, the car has to:

- collect as much solar energy as possible

- use as little energy as possible to drive at a certain speed. This means special attention to:

- the efficiency of transferring electrical energy to the wheels, and

- minimizing friction, constituted by:

- air friction (air resistance), and

- rolling friction, which in turn is affected by the weight, among other things

Solar cells

The solar cells are made of gallium arsenide (GaAs) and consist of three layers. Sunlight that penetrates the upper layer is used in the lower layers, resulting in an efficiency of over 26%. This type of solar cell is among the best available currently. Apart from efficiency, size also matters, so the entire upper surface of the Nuna 3 is covered with them, except for the cockpit.

Efficiency is optimal when the cells are hit by the solar rays perpendicularly. If not, output is reduced by roughly the cosine of the angle with the perpendicular.

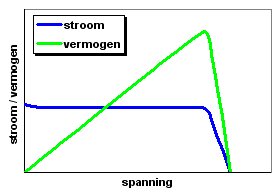

A solar cell gives a certain amount of current for a certain amount of sunlight. The voltage depends on the load (more precisely the resistance of the load). The power is the product of voltage and current and therefore also depends on the load. Over a certain voltage the current of the solar cell quickly drops to zero, as the graph illustrates.

However, the batteries have a fairly constant voltage, which also has a rather different value than that of the solar cells. So a voltage transformation is needed. A special type of DC-DC converter is used to ensure the load resistance presented to the solar cells is such that the solar cells give maximum power, so also at the top of the green line in the graph. This is called a Maximum power point tracker (MPPT). Here too, the goal is to have this conversion achieve maximum efficiency (>97%).

Aerodynamic design

The aerodynamic drag is an important part of the total resistance. Important are the frontal surface area and the coefficient of drag. The shape must be designed to preserve laminar flow, as turbulence causes increased surface drag. The ideal shape is achieved in various stages:

- Through computer simulations of the design.

- Through testing of a scale model in a wind tunnel. For example, liquid paints can be applied to see the flow of air over the surface. The photo shown was taken during one of those tests in the Low Speed Laboratory of the TU Delft.

- Through testing of the full scale car in a wind tunnel. For this, the DNW Large Low-Speed Facility (LLF) in Marknesse is used.

From meteorological data at the area where the contest is to take place, it can be concluded that there will likely be a strong side-wind. The wheel caps of the Nuna 3 are designed such that a sidewind will have a propulsory effect.

Motor

The motor is totally encased in the rear wheel to minimise loss through mechanical transmission from motor to wheel (such as in a normal car in the gear box and cardan). The motor is an improved version of the original 1993 Motor of the Spirit of Biel III by the Engineering School of Biel, Switzerland (now: Berner Fachhochschule Technik und Informatik). The improvements are due to completely redeveloped digital power electronics and control, realized 1999. They allowed for 50% more power (over 2400 W) and a 45% higher torque compared to the 1993 Spirit of Biel II. The efficiency of the total drive system (including the power electronics losses) is also improved and is now over 98%. But as the graph shows this depends somewhat on the speed and increases with speed. The design was initially made to reach its maximum performance at the normal cruising speed of the solar car at around 100 km/h.

The race

Winning the race requires not just a good vehicle but also a clever way of driving it, in accordance with the characteristics of the track. Which is why this has been researched for two months prior to the race. Height differences are mapped and linked to GPS data. From this, during the race, the optimal speed can be determined.

Despite all testing and other preparations, one uncertain factor remains; the weather. Any clouds would strongly influence the amount of sunlight that can be captured. So any weather changes along the track will have to be constantly monitored. All these data are analysed by a computer model that constantly computes the ideal speed for that moment. This equipment is built into (petrol powered) pilot cars. Through telemetry these constantly receive data about the condition of the batteries and the amount of captured sunlight.

Team

Each version of the Nuna has been built by a team consisting of students of the Delft University of Technology. The team has between ten and twenty team members. They take a year off from their studies to design and build a new version of the solar racer from scratch. In 2001 the Nuna 1 was built by the alpha-centauri team. They were provided with guidance from former astronaut Wubbo Ockels. Since 2002 the team has been called the Nuon Solar Team and have had Ockels providing advice and assistance.

Nuna 3 (2005)

Nuna 3 was one of the favourites for the 2005 edition of the World Solar Challenge with a pre-race test-drive speed of 130 km/h. The final result was that the 3021 kilometers between Darwin and Adelaide were covered in a record 29 hours and 11 minutes, averaging about 103 km/h. This is still the current record for the World Solar Challenge.

Nuna 4 (2007)

The main changes to the Nuna 4 from its predecessor the Nuna 3 are a steering wheel instead of levers, an upright seat instead of the driver lying down and a smaller solar panel of 6 m² compared to the previous 9 m². These changes were necessitated by changes in the rules prompted by alleged safety concerns and attempts to make the car more like a real car, and by reductions in the speed limit on Australian roads. The Nuna 4 won in 2007.[1]

Nuna 5 (2009)

The main changes to the Nuna 5 from its predecessor the Nuna 4 was the diminished battery weight, changing from 30 kg in 2007 to 25 kg.Other changes required cars not be allowed to race on previously used slicks (smooth tires), instead requiring profiled (treaded or grooved) tires. Also, the driver was required to sit more upright with a seating angle of, at most, 27 degrees. [2] It finished second.

Nuna 6 (2011)

The main changes to the Nuna 6 from its predecessor the Nuna 5 is the change of solar cells to Monocrystalline silicon cells in accordance with the new rules for the World solar challenge. Also the weight of the batteries has been reduced in accordance with the rules. To improve performance the weight of the car and aerodynamic drag have been reduced

Nuna 7 (2013)

The main change to the Nuna 7 from its predecessors is that it has four wheels instead of three, as required by the new rules of the World solar challenge. The vehicle is also asymmetric, as the driver's cabin is on the right side. The weight of the batteries and vehicle are barely changed with respect to its predecessor, Nuna 6. Nuna 7 won the 2013 Bridgestone World Solar Challenge.

See also

- The Twente One a competing Dutch solar car from the University of Twente.

- The SolUTra TUs car which preceded the Twente One.

- The Nuna 5 solar car of the Nuon Solar Team which came in second in 2009.

- List of solar car teams

- World Solar Challenge

References

- ^ TU Delft, Dossier Nuna 4, Retrieved on October 25, 2007.

- ^ Technical Regulations WSC 2009