Old Mortality

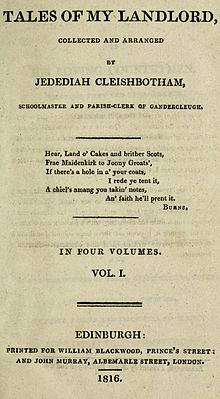

First edition title page | |

| Author | Walter Scott |

|---|---|

| Language | English, Lowland Scots |

| Series | Waverley Novels; Tales of my Landlord (1st series) |

| Genre | Historical novel |

| Publisher | William Blackwood, (Edinburgh); John Murray (London) |

Publication date | 2 December 1816[1] |

| Publication place | Scotland |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 353 (Edinburgh Edition, 1993) |

| Preceded by | The Black Dwarf |

| Followed by | Rob Roy |

Old Mortality is one of the Waverley novels by Walter Scott. Set in south west Scotland, it forms, along with The Black Dwarf, the 1st series of his Tales of My Landlord (1816). The novel deals with the period of the Covenanters, featuring their victory at Loudoun Hill (also known as the Battle of Drumclog) and their defeat at Bothwell Bridge, both in June 1679; a final section is set in 1689 at the time of the royalist defeat at Killiecrankie.

Scott's original title was The Tale of Old Mortality, but this is generally shortened in most references.

Composition and sources

[edit]On 30 April 1816 Scott signed a contract with William Blackwood for a four-volume work of fiction, and on 22 August James Ballantyne, Scott's printer and partner, indicated to Blackwood that it was to be entitled Tales of My Landlord, which was planned to consist of four tales relating to four regions of Scotland. In the event the second tale, Old Mortality, expanded to take up the final three volumes, leaving The Black Dwarf as the only story to appear exactly as intended. Scott completed The Black Dwarf in August, and composed Old Mortality during the next three months.[2]

Scott was steeped in 17th-century literature, but among the printed sources drawn on for The Tale of Old Mortality the following may be singled out for special mention:

- Memoirs of Captain John Creichton in The Works of Jonathan Swift D. D., which Scott edited in 1814

- The Secret and True History of the Church of Scotland by James Kirkton, edited by Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe in 1817

- Some Remarkable Passages of the Life and Death of Mr. Alexander Peden, by Patrick Walker (1724)

- The History of the Sufferings of the Church of Scotland, by Robert Wodrow (1721–22).[3]

Editions

[edit]Old Mortality appeared as the second, third, and fourth volumes of Tales of My Landlord, published by Blackwood's in Edinburgh on 2 December and by John Murray in London three days later. As with all the Waverley novels before 1827 publication was anonymous. The title-page indicated that the Tales were 'collected and arranged by Jedediah Cleishbotham', reinforcing the sense of a new venture moving on from the first three novels with 'the Author of Waverley' and his publishers, Archibald Constable in Edinburgh and Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown in London. The print run was 2000 copies, and the price £1 8s (£1.40).[4] Two further editions with minor changes followed in the next two months. There is no clear evidence for authorial involvement in these, or in any of the novel's subsequent appearances except for the 18mo Novels and Tales (1823) and the 'Magnum' edition. Some of the small changes to the text in 1823 are attributable to Scott, but that edition was a textual dead end. In October 1828 he provided the novel with an introduction and notes, and revised the text, for the Magnum edition in which it appeared in February to April 1830 as part of the ninth volume, the whole of the tenth, and part of the eleventh.[5]

The standard modern edition, by Douglas Mack, was published with Scott's apparently preferred title "The Tale of Old Mortality", as Volume 4b of the Edinburgh Edition of the Waverley Novels in 1993: this is based on the first edition with emendations from manuscript and the editions immediately following the initial publication; the Magnum material appears in Volume 25a.

Plot summary

[edit]After an Introduction to the Tales of My Landlord, supposedly written by the novel's (fictional) editor Jedediah Cleishbotham, the first chapter by the (fictional) author Peter Pattieson describes Robert Paterson ('Old Mortality'), a Scotsman of the 18th century, who late in life decided to travel around Scotland re-engraving the tombs of 17th-century Covenanter martyrs. Pattieson describes at length meeting Robert Paterson, hearing his anecdotes, and finding other stories of the events to present an unbiased picture.

The novel then describes a wapenshaw held in 1679 by Lady Margaret Bellenden, life-rentrix of the barony of Tillietudlem. This was a show of her support for the Royalist cause, but most of her tenants favoured the opposing Covenanters (who wanted the re-establishment of presbyterianism in Scotland) and she has to enlist her unwilling servants. After her supporters are duly mustered, the main sport is a shoot at the popinjay in which the Cavalier favourite is narrowly defeated by Henry Morton, son of a Covenanter. He is introduced to Lady Margaret and her lovely granddaughter Edith Bellenden, with whom he is in love.

During celebrations of his popinjay victory in the inn that evening, Morton stands up for John Balfour of Burley against bullying by Cavalier dragoons. That night, Burley seeks shelter at Morton's house; Morton reluctantly agrees. It emerges that Burley was one of the assassins of Archbishop James Sharp. In the morning they have to flee Cavalier patrols. As a consequence, Morton finds himself outlawed, and joins Burley in the uprising at the Battle of Drumclog. During this battle a small but well organised group of Covenanters defeated a force of dragoons led by John Graham of Claverhouse. However, after this initial success, Scott traces the growth of factionalism, which hastened its defeat at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge in 1679, by forces led by the Duke of Monmouth and John Graham of Claverhouse.

Henry Morton's involvement in the rebellion causes a conflict of loyalties for him, since Edith Bellenden belongs to a Royalist family who oppose the uprising. Henry's beliefs are not as extreme as those of Burley and many other rebel leaders, which leads to his involvement in the factional disputes. The novel also shows their oppressors, led by Claverhouse, to be extreme in their beliefs and methods. Comic relief is provided by Cuddie Headrigg, a peasant who works as a manservant to Morton. He reluctantly joins the rebellion because of his personal loyalty to Morton, as well as his own fanatical Covenanting mother, Mause Headrigg.

Following the defeat at Bothwell Bridge, Morton flees the battle field. He is soon captured by some of the extreme Covenanters, who see him as a traitor, and get ready to execute him. He is rescued by Claverhouse, who has been led to the scene by Cuddie Headrigg. Morton later witnesses the trial and torture of fellow rebels, before going into exile.

The novel ends with Morton returning to Scotland in 1689 to find a changed political and religious climate following the overthrow of James VII, and to be reconciled with Edith.

Characters

[edit]Principal characters in bold

Mr Morton of Milnewood, a Presbyterian

Henry Morton, his nephew

Alison Wilson, his housekeeper

Lady Margaret Bellenden of Tillietudlem

Edith, her granddaughter

Major Bellenden, her brother-in-law

Gudyill, her butler

Goose Gibbie, her half-witted servant

Jenny Dennison, Edith's maid

Mause Headrigg

Cuddie, her son

Lord Evandale

Lady Emily Hamilton, his sister

Niel Blane, a publican

Jenny, his daughter

Francis Stuart (Bothwell), his sergeant

Cornet Richard Grahame, his nephew

Tam Halliday, Bothwell's comrade

Gabriel Kettledrummle, Peter Poundtext, Ephraim Macbriar, and Habbakuk Mucklewraith, Covenanting preachers

John Balfour or Burley, a Covenanter

General Dalzell, his aide-de-camp

Basil Olifant

Bessie MacClure

Peggy, her granddaughter

Wittenbold, a Dutch dragoon commander

Chapter summary

[edit]Volume One

[edit]Ch. 1: An assistant schoolmaster at Gandercleugh, Peter Pattieson, tells of his encounter with Old Mortality repairing Covenanters' gravestones, and of the stories he told that form the basis of the following narrative.

Ch. 2: Lady Margaret Bellenden has difficulty in finding enough willing servants to fulfil her obligation to send a prescribed number to the wappen-schaw (muster).

Ch. 3: At the wappen-schaw Henry Morton wins the contest of shooting at the popinjay (parrot), defeating Lord Evandale and a young plebeian [later identified as Cuddie Headrigg]. Lady Margaret's half-witted servant Goose Gibbie takes a tumble.

Ch. 4: At Niel Blane's inn John Balfour (or Burley) defeats Francis Stuart (Bothwell) in a wrestling bout. After Burley has left, Cornet Grahame arrives to announce that the Archbishop of St Andrews has been murdered by a band under Burley's command.

Ch. 5: Henry shelters Burley in the stable at Milnewood, securing for him provisions obtained ostensibly for his own refreshment from the garrulous housekeeper Alison Wilson.

Ch. 6: Next morning Henry sees Burley on his way, rejecting his extremism. He abandons a plan to make a career abroad in the face of opposition by his uncle and Alison.

Ch. 7: Lady Bellenden expels Mause and Cuddie Headrigg from Tillietudlem for whiggery.

Ch. 8: Mause and Cuddie find shelter at Milnewood. Bothwell arrests Henry for succouring Burley. Mause and Cuddie prepare to leave Milnewood after she has uttered fanatically extreme Covenanting sentiments.

Ch. 9: Lady Bellenden makes Bothwell's party welcome at Tullietudlem.

Ch. 10: With Jenny Dennison's help Edith Bellenden persuades the guard Tam Halliday to allow her to see Henry Edith. She writes a letter, to be conveyed by Goose Gibbie, suggesting that her uncle Major Miles Bellenden should speak in Henry's behalf to Claverhouse.

Ch. 11: Major Bellenden arrives at Tillietudlem in response to Edith's letter, shortly followed by Claverhouse.

Ch. 12: After breakfast Claverhouse declines to spare Henry at the Major's request, and he is confirmed in his decision when Lord Evandale arrives to report that the Covenantening forces are expecting to be joined by a strong body headed by Henry. Evandale agrees at Edith's suit to intercede in Henry's behalf.

Ch. 13: An old jealousy of Henry's is reawakened by his misinterpretation of Edith's relationship with Evandale. Claverhouse agrees to spare him from instant execution at Evandale's request.

Volume Two

[edit]Ch. 1 (14): Henry discusses current affairs with Cuddie on the march under Bothwell's guard. Mause and Gabriel Kettledrummle give unbridled vent to their convictions.

Ch. 2 (15): The body arrives at Loudon Hill where the royalist force is preparing for battle with the Covenanters.

Ch. 3 (16): The Covenanters triumph in the battle: Cornet Grahame is shot before it begins, and Burley kills Bothwell in the conflict.

Ch. 4 (17): Henry, who has observed the battle, intervenes to save Evandale from Burley, enabling him to avoid captivity.

Ch. 5 (18): Kettledrummle and Ephraim Macbriar preach after the battle.

Ch. 6 (19): Major Bellenden prepares Tillietudlem for siege by the Covenanters.

Ch. 7 (20): Claverhouse provides Tillietudlem with a detachment of dragoons for its defence as the surrounding country prepares for war.

Ch. 8 (21): Burley persuades Henry to join the Covenanting forces, albeit with some misgivings.

Ch. 9 (22): Henry is horrified by the extreme views expressed at a council of the Covenanters.

Ch. 10 (23): Henry accepts Cuddie's offer to enter his service and receives from him the deceased Bothwell's pocket-book. He joins in a council of six to plan the reduction of Tillietudlem.

Ch. 11 (24): Evandale arrives at Tillietudlem. Edith is distressed to learn from Jenny Dennison that Henry has joined the Covenanters.

Ch. 12 (25): After Major Bellenden rejects a letter from Henry proposing terms of surrender there is an indecisive skirmish.

Ch. 13 (26): Leaving the Tullietudlem siege with reluctance at Burley's insistence, Henry joins in an unsuccessful attempt to take Glasgow. The Duke of Monmouth is nominated to command the royalist army in Scotland.

Ch. 14 (27): Henry returns with Peter Poundtext to Tillietudlem village and they persuade Burley to spare Evandale, captured in a sally, from execution.

Ch. 15 (28): After an appeal by Jenny Dennison to Henry, he releases Evandale, who arranges the surrender of Tillietudlem before setting out for Edinburgh to join Monmouth, in company with the women folk.

Ch. 16 (29): On the road to Edinburgh Henry briefly joins the party and discusses his conduct with Edith, as do the Bellendens and Evandale among themselves. Joining the Covenanters at Hamilton, Henry tries to keep up their spirits while seeking an accommodation with the royalists.

Ch. 17 (30): With the agreement of the Covenanting council Henry meets Monmouth to explore possible peace terms; Monmouth puts an end to the discussion by demanding that the Covenanters lay down their arms before negotiations commence.

Volume Three

[edit]Ch. 1 (31): Henry finds the Covenanters split doctrinally and tactically.

Ch. 2 (32): The Covenanters are defeated and dispersed at the battle of Bothwell Bridge.

Ch. 3 (33): Henry is threatened with death by a group of Cameronians, including Macbriar and Habakkuk Meiklewrath. He is rescued by Claverhouse.

Ch. 4 (34): Claverhouse shows great calmness in disposing of the Cameronians.

Ch. 5 (35): Claverhouse and Henry debate on the way to Edinburgh and witness the procession of prisoners into the city.

Ch. 6 (36): The Privy Council of Scotland sentences Henry to exile before pardoning Cuddie and torturing Macbriar and condemning him to death.

Ch. 7 (37): After ten years Henry returns to Scotland, visiting Cuddie incognito at his cottage near Bothwell Bridge to ascertain the present state of affairs, including Basil Olifant's success in obtaining ownership of Tillietudlem and Edith's engagement to Evandale.

Ch. 8 (38): Jenny Dennison, now Headrigg, recognises Henry but advises Cuddie that to acknowledge him would be to endanger their tenancy. Evandale asks Edith to marry him before he leaves for the campaign against Claverhouse (now Viscount Dundee) but after catching sight of Henry looking in through the window she breaks off the engagement.

Ch. 9 (39): Henry returns to Milnewood to learn that his uncle is dead.

Ch. 10 (40): Henry tells his story to Alison and passes on.

Ch. 11 (41): Following directions from Niel Blane, Henry arrives at Bessie Maclure's inn.

Ch. 12 (42): Bessie tells her own story and updates Henry on Burley's recent history and his current retreat at the Black Linn of Linklater.

Ch. 13 (43): Bessie's granddaughter Peggy conducts Henry to the Black Linn where Burley has a document which would restore Edith to Tillietudlem in place of Olifant, but Henry refuses his terms. Returning to Bessie's inn he overhears two dragoons plotting to attack Evandale on Olifant 's behalf.

Ch. 14 (44): Henry's warning note to Evandale, entrusted to Goose Gibbie, miscarries and Evandale is killed, as is Burley on the arrival of a party of Dutch dragoons under Wittenbold.

Conclusion: At Martha Buskbody's request Peter Pattieson sketches in the later history of the main surviving characters.

Peroration: Jedidiah Cleishbotham, who has arranged for Pattieson's manuscript to be published, indicates that more volumes of the Tales of my Landlord will be forthcoming.

Historical background

[edit]In an introduction written by Scott in 1830, he describes his own chance meeting with 'Old Mortality' at Dunottar, which he describes as having happened about 30 years before the time of writing.[6]

The novel centres on the actual events of a Covenanter uprising in 1679, and describes the battles of Drumclog and Bothwell Bridge. The character of Henry Morton is fictional, as is Tillietudlem Castle, but readers identified the place with Craignethan Castle which Scott had visited. This castle soon attracted literary tourists, and a railway halt built nearby became the hamlet of Tillietudlem.[7]

Reception

[edit]Most of the reviewers rated Old Mortality considerably higher than The Black Dwarf, with particular appreciation of the characters and descriptions, though there were several objections to the weakness of the hero Henry Morton.[8] Although four critics, including Francis Jeffrey in The Edinburgh Review, judged the presentation of the Covenanters and the royalists to be fair, there were several assertions that the Covenanters were caricatured and the royalists whitewashed, most notably in a long (and otherwise generally appreciative) article by the Rev. Thomas McCrie the elder in The Edinburgh Christian Instructor.[9] Scott himself responded indirectly to McCrie's criticisms in an anonymous self-review for The Quarterly Review. The Eclectic Review accused Scott of distorting and diminishing history for the sake of amusing his readers, while admitting he did it well. Henry Duncan, who opened the first savings bank, published a set of three novels attempting to counteract the negative view of the Covenanters given in Old Mortality.

Adaptations and cultural references

[edit]

The play Têtes rondes et Cavaliers (1833) by Jacques-François Ancelot and Joseph Xavier Saintine is based on Scott's novel.[10]

Vincenzo Bellini's opera I puritani (1835), with a libretto written by Italian emigre in Paris, Count Carlo Pepoli, is in turn based on that play. It has become one of Bellini's major operas.[10]

Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poetical illustration ![]() Black Linn of Linklater. to a painting by Alexander Chisholm is effectively a eulogy on Sir Walter Scott himself following his death and also recounts his visit to Italy. The titled picture is of a location mentioned in Old Mortality.[11]

Black Linn of Linklater. to a painting by Alexander Chisholm is effectively a eulogy on Sir Walter Scott himself following his death and also recounts his visit to Italy. The titled picture is of a location mentioned in Old Mortality.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ "Old Mortality". Edinburgh University Library. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Walter Scott, Black Dwarf, ed. P. D. Garside (Edinburgh, 1993), 125–35; Walter Scott, The Tale of Old Mortality, ed. Douglas Mack (Edinburgh, 1993),362.

- ^ The Tale of Old Mortality, ed. Mack, 361, 435–36.

- ^ William B. Todd and Ann Bowen, Walter Scott: A Bibliographical History 1796–1832, 414.

- ^ The Tale of Old Mortality, ed. Mack, 372–82.

- ^ "Introduction to Old Mortality" by Walter Scott (1830)

- ^ "Craignethan Castle". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ For a full list of contemporaneous British reviews see William S. Ward, Literary Reviews in British Periodicals, 1798‒1820: A Bibliography, 2 vols (New York and London, 1972), 2.486. For an earlier annotated list see James Clarkson Corson, A Bibliography of Sir Walter Scott (Edinburgh and London, 1943), 210‒11.

- ^ M'Crie, Thomas (1857). M'Crie, Thomas (ed.). Works of Thomas M'Crie, D.D. Volume 4: review of "Tales of my Landlord". Vol. 4. Edinburgh: William Blackwood & sons. pp. 5-128.

- ^ a b "I Puritani". Opera-Arias.com. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1836). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837. Fisher, Son & Co.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1836). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837. Fisher, Son & Co.

External links

[edit]- Old Mortality at Project Gutenberg

Old Mortality public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Old Mortality public domain audiobook at LibriVox