Mandalay (poem)

"Mandalay" is a poem by Rudyard Kipling, written and published in 1890,[a] and first collected in Barrack-Room Ballads, and Other Verses in 1892. The poem is set in colonial Burma, then part of British India. The protagonist is a Cockney working-class soldier, back in grey, restrictive London, recalling the time he felt free and had a Burmese girlfriend, now unattainably far away.[2]

The poem became well known,[3] especially after it was set to music by Oley Speaks in 1907, and was admired by Kipling's contemporaries, though some of them objected to its muddled geography.[4] It has been criticised as a "vehicle for imperial thought",[5] but more recently has been defended by Kipling's biographer David Gilmour and others. Other critics have identified a variety of themes in the poem, including exotic erotica, Victorian prudishness, romanticism, class, power, and gender.[2][6]

The song, with Speaks's music, was sung by Frank Sinatra with alterations to the text, such as "broad" for "girl", which were disliked by Kipling's family. Bertolt Brecht's "Mandalay Song", set to music by Kurt Weill, alludes to the poem.

Development

[edit]

Background

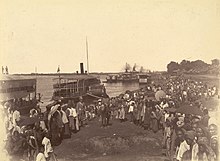

[edit]The Mandalay referred to in this poem was the sometime capital city of Burma, which was part of British India from 1886 to 1937, and a separate British colony from 1937 to 1948. It mentions the "old Moulmein pagoda", Moulmein being the Anglicised version of present-day Mawlamyine, in South eastern Burma, on the eastern shore of the Gulf of Martaban. The British troops stationed in Burma travelled up and down the Irrawaddy River on paddle steamers run by the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company (IFC). Rangoon to Mandalay was a 700 km (435 mi) trip, and during the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885, 9,000 British and Indian soldiers were transported by a fleet of paddle steamers ("the old flotilla" of the poem) and other boats to Mandalay from Rangoon. Guerrilla warfare followed the occupation of Mandalay, and British regiments remained in Burma for several years.[7][8]

Kipling mentions the Burmese royal family of the time: "An' 'er name was Supi-yaw-lat—jes' the same as Theebaw's Queen." Thibaw Min (1859–1916, often spelt Theebaw at that time) was the last reigning king of Burma, with his palace in Mandalay. He married his half-sister, Supayalat, shortly before becoming king in 1878 in a bloody palace coup supposedly engineered by his mother-in-law. He introduced a number of reforms but, in 1885, made the mistake of attempting to regain control of Lower Burma from the British forces that had held it since 1824. The result was a British invasion that immediately sent Thibaw and Supayalat into exile in India. So, to the soldier in Kipling's poem, his and her names are familiar, as the last and very recent royalty of a British colony.[9][10][11]

Writing

[edit]Rudyard Kipling's poem Mandalay was written between March and April 1890, when the British poet was 24 years old. He had arrived in England in October the previous year, after seven years in India. He had taken an eastward route home, travelling by steamship from Calcutta to Japan, then to San Francisco, then across the United States, in company with his friends Alex and "Ted" (Edmonia) Hill. Rangoon had been the first port of call after Calcutta; then there was an unplanned stop at Moulmein.[1] Kipling was struck by the beauty of the Burmese girls, writing at the time:[12]

I love the Burman with the blind favouritism born of first impression. When I die I will be a Burman … and I will always walk about with a pretty almond-coloured girl who shall laugh and jest too, as a young maiden ought. She shall not pull a sari over her head when a man looks at her and glare suggestively from behind it, nor shall she tramp behind me when I walk: for these are the customs of India. She shall look all the world between the eyes, in honesty and good fellowship, and I will teach her not to defile her pretty mouth with chopped tobacco in a cabbage leaf, but to inhale good cigarettes of Egypt's best brand.[12]

Kipling claimed that when in Moulmein, he had paid no attention to the pagoda his poem later made famous, because he was so struck by a Burmese beauty on the steps. Many Westerners of the era remarked on the beauty of Burmese women.[13]

Publication

[edit]Mandalay first appeared in the Scots Observer on 21 June 1890.[1] It was first collected into a book in Barrack-Room Ballads, and Other Verses in 1892.[1] It subsequently appeared in several collections of Kipling's verse, including Early Verse in 1900, Inclusive Verse in 1919, and Definitive Verse in 1940. It appears also in the 1936 A Kipling Pageant, and T. S. Eliot's 1941 A Choice of Kipling's Verse.[1]

Structure

[edit]The poem has the rhyming scheme AABB traditional for ballad verse. However, Kipling begins the poem with the "stunningly memorable" AABBBBBBBB, the A being sea - me, and the B including say - lay - Mandalay.[5] Another ballad-like feature is the use of stanzas and refrains, distinguished both typographically and by the triple end rhymes of the refrains. The poem's ending closely echoes its beginning, again in the circular manner of a traditional ballad, making it convenient to memorise, to recite, and to sing.[5] The metre in which the poem is written is trochaic octameters, meaning there are eight feet, each except the last on the line consisting of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one. The last foot is catalectic, consisting only of the stressed syllable:[14][15]

Ship me / somewheres / east of / Suez, / where the / best is / like the / worst,

Where there / aren't no / Ten Com/mandments / an' a / man can / raise a / thirst;

For the / temple/-bells are / callin', / and it's / there that / I would / be—

By the / old Moul/mein Pa/goda, / looking / lazy / at the / sea.

In Kipling's time, the poem's metre and rhythm were admired; in The Art of Verse Making (1915), Modeste Hannis Jordan wrote: "Kipling has a wonderful 'ear' for metre, for rhythm. His accents fall just right, his measure is never halting or uncertain. His 'Mandalay' may be quoted as an excellent example of rhythm, as easy and flowing as has ever been done".[16]

The poet and critic T. S. Eliot, writing in 1941, called the variety of forms Kipling devised for his ballads "remarkable: each is distinct, and perfectly fitted to the content and the mood which the poem has to convey."[17]

Themes

[edit]Colonialism

[edit]

For

[edit]The literary critic Sharon Hamilton, writing in 1998, called the 1890 "Mandalay" "an appropriate vehicle for imperial thought".[5] She argued that Kipling "cued the Victorian reader to see it as a 'song of the Empire'" by putting it in the "border ballad" song tradition, where fighting men sang of their own deeds, lending it emotional weight.[5] She further suggested that, since Kipling assembled his 1892 Barrack-Room Ballads (including "Mandalay") in that tradition during a time of "intense scrutiny" of the history of the British ballad, he was probably well aware that "Mandalay" would carry "the message of...submission of a woman, and by extension her city, to a white conqueror".[5] She argues that the soldier is grammatically active while the "native girl" is grammatically passive, indicating "her willing servitude".[5] Hamilton sees the fact that the girl was named Supayalat, "jes' the same as Theebaw's Queen", as a sign that Kipling meant that winning her mirrored the British overthrow of the Burmese monarchy.[4]

Against

[edit]Andrew Selth commented of Hamilton's analysis that "It is debatable whether any of Kipling's contemporaries, or indeed many people since, saw the ballad in such esoteric terms, but even so it met with an enthusiastic reception."[4] In 2003, David Gilmour argued in his book The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling that Kipling's view of empire was far from jingoistic colonialism, and that he was certainly not racist. Instead, Gilmour called "Mandalay" "a poem of great charm and striking inaccuracy",[18][19] a view with which Selth concurs. Selth notes that contemporary readers soon noticed Kipling's inaccurate geography, such as that Moulmein is 61 kilometres (38 miles) from the sea, which is far out of sight, and that the sea is to the west of the town, not east.[4][b]

Ian Jack, in The Guardian, wrote that Kipling was not praising colonialism and empire in "Mandalay". He explained that Kipling did write verse that was pro-colonial, such as "The White Man's Burden",[c] but that "Mandalay" was not of that kind.[2] A similar point was made by the political scientist Igor Burnashov in an article for the Kipling Society, where he writes that "the moving love of the Burmese girl and British soldier is described in a picturesque way. The fact that the Burmese girl represented the inferior and the British soldier superior races is secondary, because Kipling makes here a stress on human but not imperial relations."[20]

Romanticism

[edit]

Hamilton noted, too, that Kipling wrote the poem soon after his return from India to London, where he worked near a music hall. Music hall songs were "standardized" for a mass audience, with "catchiness" a key quality.[5] Hamilton argued that, in the manner of music hall songs, Kipling contrasts the exotic of the "neater, sweeter maiden" with the mundane, mentioning the "beefy face an' grubby 'and" of the British "'ousemaids".[5] This is paralleled, in her view, with the breaking of the rhyming scheme to ABBA in the single stanza set in London, complete with slightly discordant rhymes (tells - else; else - smells) and minor dissonance, as in "blasted English drizzle", a gritty realism very different, she argues, from the fantasizing "airy nothings" of the Burma stanzas with their "mist, sunshine, bells, and kisses".[5] She suggests, too, that there is a hint of "Minstrelsy" in Mandalay, again in the music hall tradition, as Kipling mentions a banjo, the instrument of "escapist sentimentality".[5] This contrasted with the well-ordered Western musical structure (such as stanzas and refrains) which mirrored the ordered, systematic nature of European music.[5]

Michael Wesley, reviewing Andrew Selth's book on "The Riff from Mandalay", wrote that Selth explores why the poem so effectively caught the national mood. Wesley argues that the poem "says more about the writer and his audience than the subject of their beguilement."[6] He notes that the poem provides a romantic trigger, not accurate geography; that the name Mandalay has a "falling cadence ... the lovely word has gathered about itself the chiaroscuro of romance." The name conjures for Wesley "images of lost oriental kingdoms and tropical splendour."[6] Despite this, he argues, the name's romance derives "solely" from the poem, with couplets like[6]

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say:

'Come you back, you British soldier; come you back to Mandalay!'

The literary critic Steven Moore wrote that in the "once-popular" poem, the lower-class Cockney soldier extols the tropical paradise of Burma, drawn both to an exotic lover and to a state of "lawless freedom" without the "Ten Commandments". That lover was, however, now way out of reach, "far removed from...real needs and social obligations."[14]

Selth identified several interwoven themes in the poem: exotic erotica; prudish Victorian Britain, and its horror at mixed marriages; the idea that colonialism could uplift "oppressed heathen women"; the conflicting missionary desire to limit the behaviour of women in non-prudish societies.[6] In Selth's view, Mandalay avoids the "austere morality, hard finance, [and] high geopolitics" of British imperialism, opting instead for "pure romanticism", or — in Wesley's words — "imperial romanticism".[6]

A common touch

[edit]

Eliot included the poem in his 1941 collection A Choice of Kipling's Verse, stating that Kipling's poems "are best when read aloud...the ear requires no training to follow them easily. With this simplicity of purpose goes a consummate gift of word, phrase, and rhythm."[17]

In Jack's view, the poem evoked the effect of empire on individuals. He argued that Kipling was speaking in the voice of a Cockney soldier with a Burmese girlfriend, now unattainably far away. He argued that the poem's 51 lines cover "race, class, power, gender, the erotic, the exotic and what anthropologists and historians call 'colonial desire'."[2] Jack noted that Kipling's contemporaries objected not to these issues but to Kipling's distortions of geography, the Bay of Bengal being to Burma's west not east, so that China was not across the Bay.[2]

Impact

[edit]According to Selth, Mandalay had a significant impact on popular Western perception of Burma and the far East. It was well known in Britain, America, and the English-speaking colonies of the British Empire. The poem was widely adapted and imitated in verse and in music, and the musical settings appeared in several films. The ballad style "lent itself easily to parody and adaption", resulting in half-a-dozen soldiers' songs, starting as early as the 1896 campaign in Sudan:[4]

By the old Soudani Railway, looking southward from the sea,

There's a camel sits a'swearin' – and, worse luck, belongs to me:

I hate the shadeless palm-tree, but the telegraphs they say,

'Get you on, you 'Gippy soldier, get you on to Dongolay.'[4]

Selth noted that the poem's name became commercially valuable; some 30 books have titles based directly on the poem, with names such as The Road from Mandalay and Red Roads to Mandalay.[4] In 1907, H. J. Heinz produced a suitably spicy "Mandalay Sauce", while a rum and fruit juice cocktail was named "A Night in Old Mandalay".[4]

In music

[edit]

Kipling's text was adapted by Oley Speaks[21] for what became his best-known song "On the Road to Mandalay", which was popularized by Peter Dawson.[22] Speaks sets the poem to music in 4

4 time, marked Alla Marcia; the key is E-flat major.[21][23] This version largely replaced six earlier musical settings of Mandalay (by Gerard Cobb (1892), Arthur Thayer (1892), Henry Trevannion (1898), Walter Damrosch (1898), Walter Hedgcock (1899), and Arthur Whiting (1900); Percy Grainger composed another in 1898, but did not publish it).[4] The total number of settings is now at least 24, spanning jazz, ragtime, swing, pop, folk, and country music; most of them use only the first two and the last two stanzas, with the chorus.[4] Versions also exist in French, Danish, German, and Russian.[4]

Arranged and conducted by Billy May, Speaks's setting appears in Frank Sinatra's album Come Fly with Me. Kipling's daughter and heiress objected to this version, which turned Kipling's Burma girl into a Burma broad, the temple-bells into crazy bells, and the man, who east of Suez can raise a thirst, into a cat.[22] Sinatra sang the song in Australia in 1959 and relayed the story of the Kipling family's objections to the song.[24]

Bertolt Brecht referred to Kipling's poem in his Mandalay Song, which was set to music by Kurt Weill for Happy End and Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.[25][26][27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It appeared in the Scots Observer on 21 June 1890.[1]

- ^ However, the line in question may be read as describing the dawn coming out of China (sun rises in the east) as the sunrise moves across the bay (east to west), not that Kipling is saying China is to the west of Burma.

- ^ However, Jack noted that it was insensitive of the then Foreign Secretary, Boris Johnson, to quote Kipling in a former British colony in 2017.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Mandalay". The Kipling Society. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Jack, Ian (7 October 2017). "Boris Johnson was unwise to quote Kipling. But he wasn't praising empire". The Guardian.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey (May 2008). "Rudyard Kipling and Burma". Facts and Details. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Selth, Andrew (2015). "Kipling, 'Mandalay' and Burma In The Popular Imagination". Southeast Asia Research Centre Working Paper Series (161). Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hamilton, Sharon (June 1998). "Musicology as Propaganda in Victorian Theory and Practice". Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal. 31 (2): 35–56. JSTOR 44029771.

- ^ a b c d e f Wesley, Michael (22 February 2017). "A poem and the politics of high imperialism". New Mandala.

- ^ Chubb, Capt H. J.; Duckworth, C. L. D. (1973). The Irrawaddy Flotilla Company 1865-1950. National Maritime Museum.

- ^ Webb, George (16 June 1983). "Kipling's Burma: A Literary and Historical Review | An address to the Royal Society for Asian Affairs". The Kipling Society. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Synge, M. B. (2003). "The Annexation of Burma". The Growth of the British Empire. The Baldwin Project. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Christian, John LeRoy (1944). "Thebaw: Last King of Burma". The Journal of Asian Studies. 3 (4): 309–312. doi:10.2307/2049030. JSTOR 2049030. S2CID 162578447.

- ^ Thant, Myint U (26 March 2001). The Making of Modern Burma (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-79914-0.

- ^ a b From Sea to Sea (1899) Volume 2 Chapter 2 telelib.com

- ^ Selth 2016, p. 24.

- ^ a b Moore, Steven (2015). William Gaddis: Expanded Edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-62892-646-0.

- ^ Fenton, James (2003). An Introduction to English Poetry. Penguin. pp. 39–43. ISBN 978-0-14-100439-6. OCLC 59331807.

- ^ Hannis Jordan, Modeste (1915). The Art of Verse Making. New York: The Hannis Jordan Company. pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Eliot, T. S. (1963) [1941]. A Choice of Kipling's Verse (Paperback ed.). Faber. p. 11. ISBN 0-571-05444-7.

- ^ Gilmour, David (2003). The long recessional : the imperial life of Rudyard Kipling. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6518-6. OCLC 59367512.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (13 May 2003). "At last, Kipling is saved from the ravages of political correctness". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ Burnashov, Igor (2001). "Rudyard Kipling and the British Empire". The Kipling Society. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2018. (Notes Archived 8 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b "On the Road to Mandalay (Speaks, Oley)". IMSLP Petrucci Music Library. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ a b Selth 2016, pp. 112 and throughout.

- ^ "On the road to Mandalay". Duke University Libraries. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ Friedwald, Will; Bennett, Tony (2018). Sinatra! The Song Is You: A Singer's Art. Chicago Review Press. p. 563. ISBN 978-1-61373-773-6.

- ^ "Happy End (1929)". The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music. Retrieved 1 June 2018. A recording is linked from the synopsis and song list.

- ^ "Mandalay". The Kipling Society. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Selth 2016, p. 109.

Sources

[edit]- Selth, Andrew (2016). Burma, Kipling and Western Music: The Riff from Mandalay. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1317298908.