Paleoart

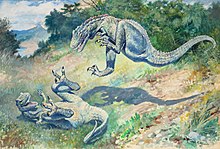

Paleoart (also spelled palaeoart) is any original artistic manifestation that attempt to reconstruct or depict prehistoric life according to the current knowledge and scientific evidence at the moment of creating the artwork.[1] The term paleoart was introduced in the late 1980s by Mark Hallett for art that depicts subjects related to paleontology.[2] These may be representations of fossil remains or depictions of the living creatures and their ecosystems. The term is a portmanteau of “art” and the ancient Greek word for old.

Production

The work of paleoartists is not mere fantasy of an artist's imagination but rather consists of cooperative discussions among experts and artists.[3][4] When attempting to reconstruct an extinct animal, the artist must utilise an almost equal mixture of artistry and scientific knowledge. The artist James Gurney, known for the Dinotopia series of fiction books, has described the interaction between scientists and artists as the artist being the eyes of the scientist, since his illustrations bring shape to the theories; palaeoart determines how the public perceives long extinct animals.[5]

Scientific impact

Extinct marine animals were some of the first to be restored as in life.[6] Art has been important in disseminating knowledge of dinosaurs since the term was introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842. With Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Owen helped create the first life-size sculptures depicting dinosaurs as he thought they may have appeared. Some models were initially created for the Great Exhibition of 1851, but 33 were eventually produced when the Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham, in South London. Owen famously hosted a dinner for 21 prominent men of science inside the hollow concrete Iguanodon on New Year's Eve 1853. However, in 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Gideon Mantell had realised that Iguanodon, of which he was the discoverer, was not a heavy, pachyderm-like animal,[7] as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs; his death left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, and so Owen's vision of dinosaurs became that seen by the public. He had nearly two dozen lifesize sculptures of various prehistoric animals built out of concrete sculpted over a steel and brick framework; two Iguanodon, one standing and one resting on its belly, were included. The dinosaurs remain in place in the park, but their depictions are now outdated in many respects.

A 2013 study found that older paleoart was still influential in popular culture long after new discoveries made them obsolete. This was explained as cultural inertia.[8] In a 2014 paper, Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway outlined the historical significance of paleoart, and lamented its current state.[9]

Recognition

Since 1999, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has awarded the John J. Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize for achievement in the field. The society says that paleoart "is one of the most important vehicles for communicating discoveries and data among paleontologists, and is critical to promulgating vertebrate paleontology across disciplines and to lay audiences".[10] The SVP is also the site of the occasional/annual "PaleoArt Poster Exhibit", a juried poster show at the opening reception of the annual SVP meetings.

The Museu da Lourinhã organizes the annual International Dinosaur Illustration Contest[11] for promoting the art of dinosaur and other fossils.

Notable, influential paleoartists

- Mauricio Anton 1990s-Present, biggest influence in prehistoric mammals

- Robert T. Bakker 1960s-90s, led the Renaissance of "active" dinosaurs

- Zdeněk Burian 1960s-81, cultural influence during these years (i.e. toys)

- Gerhard Heilmann 1920s, first to restore tail-in-air dinosaurs

- Doug Henderson 1980s-00s

- Charles R. Knight 1890s-1940s, biggest influence of early 20th century (i.e. movies)

- Gregory S. Paul 1970s-Present, biggest influence of late 20th century-21st century

- Rudolph F. Zallinger 1950s-60s, cultural influence during these years (i.e. toys)

Past 2D paleoartists

- Othenio Abel deceased, active 1910s

- James E. Allen deceased, active 1950s

- Robert T. Bakker active 1960-90s, led Renaissance

- Bill Berry deceased, active 1960s

- Zdeněk Burian deceased, active 1960s-81

- Kenneth Carpenter active 1980s

- Henry de la Beche deceased, active 1900s

- Amédée Forestier deceased 1930, active 1880s-1920s, notable for his Nebraska Man and Glastonbury Lake Village illustrations

- Joseph M. Gleeson, born 1861, active in late 19th and early 20th centuries

- Heinrich Harder deceased, active 1910s-20s

- Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins deceased, active 1850s-1870s

- Gerhard Heilmann deceased, active 1920s

- Ferdinand von Hochstetter deceased, active 1850s-1870s

- Othniel Charles Marsh deceased, active 1890s

- Eleanor R. Kish deceased, active 1970s-90s

- Charles R. Knight deceased, active 1890s-1940s

- John Martin deceased, active 1830s

- Jay Matternes deceased, active 1950s-70s

- William Diller Matthew deceased, active 1900s-10s

- Edward Newman deceased, active 1840s

- George Olshevsky active 1980s

- Richard Owen deceased, active 1850s

- Ernest Untermann deceased, active 1930s

- Alice B. Woodward deceased, active 1910s

- Rudolph F. Zallinger deceased, active 1950s-60s

Post-Renaissance, published 2D paleoartists

- Andrey Atuchin 2000s-

- Marco Ansón 2010s-

- Wayne D. Barlowe 1990s

- Alain Beneteau 2000s-

- John Bindon 1990s-

- Davide Bonadonna 2000s-

- Karen Carr 2000s-

- John Conway 2000s-

- Julius T. Csotonyi 2000s-

- Ricardo Delgado 1990s

- Alex Ebel 2000s

- James Gurney 1990s-

- Sergei Krasovskiy 2010s-

- Raúl Martín 2000s-

- John McLoughlin 1970s

- Josef Moravec 1980s-

- Robert (Bob) Nicholls 1990s-

- William Parsons 1990s-

- Gregory S. Paul 1980s-

- Luis Rey 1980s-

- John Sibbick 1980s-

- Jan Sovak 1980s-

- William Stout 1970s-

- Oda Takashi 1990s-

- Peter Trusler 1990s-

- Scott Hartman 1990s-

- Mark Witton 2000s-

- Øyvind M. Padron 2000s-

- Satoshi Kawasaki 2000s-

- Emily Willoughby 2000s-

- Todd Marshall 2000s-

- Zhao Chuang 2000s-

- Nobu Tamura 2000s-

- Frederik Spindler 2000s-

- Daniel Bensen 2000s-

- Mineo Shiraishi 1990s-

- Darren Naish 1990s-

- Jaime A. Headden 2000s-

- Ville Sinkkonen 2000s-

- Felipe A. Elias 2000s-

- Vladmir Nikolov 2000s-

- Julio Lacerda 2000s-

- Matthew Martyniuk 2000s-

- Tuomas Koivurinne 1990s-

- João Boto 2000s-

- Jordan Mallon 2000s-

- Timothy J. Bradley 2000s-

- Kayomi Tukimoto 2000s-

- Keiji Terakoshi 1980s-

- Masato Hattori 2010s-

- Xing Lida 2000s-

- Cheung Chungtat 2000s-

Current 3D paleoartists

- Kennis & Kennis 1990s-

- Brian Cooley 1980s-

- Elizabeth Daynés 1980s-

- Gary Staab 1990s-

- Jorge Blanco 1990s-

- Michael Trcic 1990s-

- Robert (Bob) Nicholls 1990s-

- Galileo Hernandez 2000s-

- David Krentz 2000s-

- David Rankin 2000s-

- Mark Witton 2000s-

- Paul Sereno 2000s-

- Vlad Konstantinov 2000s-

Past 3D paleoartists

- Charles Whitney Gilmore

- Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins 1850s-1870s

- Charles R. Knight 1900s-40s

- Richard Swann Lull 1910s

References

- ^ Ansón et al., (2015) Paleoart: term and conditions (A survey among paleontologists) in: Current trends in Paleontology and Evolution, 28-24 pp.

- ^ Hallett M (1986) The scientific approach of the art of bringing dinosaurs back to life, in: Czerkas SJ, Olson EC (Eds.), Dinosaurs Past and Present 1. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles Count in association with University of Washington Press, 97-113 pp.

- ^ Catherine Thimmesh: Scaly Spotted Feathered Frilled: How Do We Know What Dinosaurs Really Looked Like? Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013, 57 pages with paleoart illustrations by John Sibbick, Greg Paul, Mark Hallett et al., ISBN 978-0-547-99134-4.

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/science/lost-worlds/2012/sep/03/drawing-dinosaurs-palaeoart

- ^ Gurney J. (2009) Imaginative Realism: How to Paint What Doesn't Exist. Andrews McMeels Publishing. p. 78.

- ^ Davidson, J. P. (2015). "Misunderstood Marine Reptiles: Late Nineteenth-Century Artistic Reconstructions of Prehistoric Marine Life". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 118: 53–67. doi:10.1660/062.118.0107.

- ^ Mantell, Gideon A. (1851). Petrifications and their teachings: or, a handbook to the gallery of organic remains of the British Museum. London: H. G. Bohn. OCLC 8415138.

- ^ Ross, R. M.; Duggan-Haas, D.; Allmon, W. D. (2013). "The Posture of Tyrannosaurus rex: Why Do Student Views Lag Behind the Science?". Journal of Geoscience Education. 61: 145. Bibcode:2013JGeEd..61..145R. doi:10.5408/11-259.1.

- ^ Witton, M. P., Naish, D. and Conway, J. (2014). State of the Palaeoart. Palaeontologia Electronica Vol. 17, Issue 3; 5E: 10p

- ^ Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Retrieved on Februar 14, 2014.

- ^ International Dinosaur Illustration Contest