Peach War

| Peach Tree War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Northern War; American Indian Wars | |||||||||

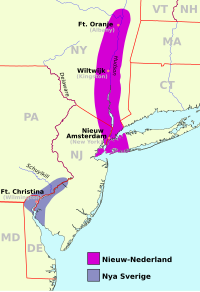

An approximation of the borders of New Netherland and New Sweden, c. 1650. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Susquehannock and allied tribes | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Around 600 | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown; 150 hostages taken by Native Americans | ||||||||

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

The Peach Tree War, also known as the Peach War, was a large scale attack by the Susquehannock Nation and allied Native Americans on several New Netherland settlements along the Hudson River (then called the North River), centered on New Amsterdam and Pavonia on September 15, 1655.

The attack was motivated by the Dutch conquest of New Sweden, a close trading partner and protectorate of the Susquehannock. The attack was a decisive victory for the Native Americans, and many outlying Dutch settlements were forced to temporarily garrison in Fort Amsterdam. Some of these settlements, such as the Staten Island colony, were completely abandoned; while others were soon repopulated (and equipped with better defenses), as Director-General Stuyvesant shortly repurchased the rights to settle the west bank of the North River from the Native Americans.

Background

In March 1638, Swedish colonists led by Peter Minuit landed in what is today Wilmington, Delaware, proclaiming the west bank of the Delaware River to be "New Sweden". The area had previously been claimed by both the English and the Dutch but, in part because of their inability to come to terms with the dominant power in the area, the Susquehannock, neither had managed more than marginal occupation. As a dismissed Director of the Dutch West India Company's New Netherland colony, Minuit was familiar with the terrain and local custom and quickly "purchased" the land (really, the right to settle) from the Susquehannock. The Susquehannock were mistrustful of the Dutch due to their close alliance with the Susquehannocks' rivals the Iroquois Confederation. They had lost their English trading partner when the new colony of Maryland had forced out William Claiborne's trading network centered on Kent Island. The Susquehannock quickly became New Sweden's main supplier of furs and pelts and customers for European manufactured goods. In the process, New Sweden became a protectorate and tributory of the Susquehannock nation, which was perhaps the leading power on the Eastern seaboard at the time.

The English and the Dutch both rejected Sweden's right to their colony, but the Dutch had greater reason for concern since they had already discovered that the Delaware River began above the 42nd parallel north and the extent of their North American claim.[1] In 1651 they attempted to consolidate power by combining forces previously stationed at the factorijs at Fort Beversreede and Fort Nassau. They relocated the latter structure 6.5 mi (10.5 km) downstream of the Swedish Fort Christina, naming it Fort Casimir. On Trinity Sunday in 1654, Johan Risingh, Commissary and Councilor to New Sweden Governor Lt. Col. Johan Printz began his attempt to expel the Dutch from the Delaware Valley. Fort Casimir was assaulted, surrendered, and renamed Fort Trefaldighet (English: Fort Trinity), leaving Swedes in complete possession of their colony. On June 21, 1654, the Indians met with the Swedes to reaffirm their agreements. Between September 11–15, 1655 an armed squadron of ships under the direction of Director-General Peter Stuyvesant seized New Sweden.[2][3] A few days later, the Susquehannock retaliated.

The attack

Though their territory was further inland and to the south, the Susquehannocks had achieved a dominant political and military position in relation to the Lenape. This allowed them to assemble an army of warriors from multiple allied and neighboring groups that included the local population. An army of six hundred warriors landed in New Amsterdam (Lower Manhattan), wreaking havoc, without killing, through the narrow streets of the town which was mostly undefended, as the bulk of the garrison was in New Sweden. They later crossed the North River and attacked Pavonia (Jersey City).[4] One hundred fifty hostages were taken and held at Paulus Hook.[5] Farms at Harlem, Staten Island, and the Bronx were also attacked. Stuyvesant, who had led the assault on New Sweden, hurried back to his capital on news of the attack. When later ransomed, the settlers took temporary refuge in New Amsterdam, and the settlements on the west shore of the river were depopulated.

Impact and aftermath

At the time, the New Netherland colony may not have understood the Susquehannocks' attack as a retaliation for the Dutch conquest of New Sweden, although the records show that the Swedes of the Zuydt Rivier (Delaware Valley) were aware of the Susquehannock motive.[1] The New Netherland colonists believed the attack was motivated by the murder of a young Wappinger woman named Tachiniki, whom a Dutch settler killed for stealing a peach – an incident that had raised intercultural tensions shortly before the assault.[6]: 70

After ransoming the hostages at Paulus Hook, Stuyvesant repurchased the right to settle the area between the Hudson and Hackensack rivers from the Native Americans and established the fortified hamlet of Bergen (at today's Bergen Square in Jersey City),[7] and required blockhouses to be established there and other outlying towns.[8][9]

The nascent colony of Cornelis Melyn on Staten Island was abandoned. Colen Donck (at today's Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx), one of the farms known to have been raided and burned, was that of democratic reformer and champion of local self-rule Adriaen van der Donck. Records show van der Donck to have been alive in August and dead by the following January, and indicate that there was some sort of inquiry into the sacking of his home in the raids. As a consequence, it has been speculated that he may have died in, or as a consequence of, the "war," although there is no definitive record of his manner of death. If so, this would be ironic both because van der Donck was a respectful pioneer in Native American ethnography and linguistics and because he was the political nemesis of Stuyvesant.

See also

References

- ^ a b Russell Shorto (2004). The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. Random House. ISBN 1-4000-7867-9.

- ^ "Site Of Fort Casimir". Delaware Public Archives. State of Delaware. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- ^ Siege of Christina Fort, 1655, University of South Florida, 2014, accessed January 9, 2014

- ^ Edward Manning Ruttenber (1992). Indian Tribes of Hudson's River: To 1700. Hope Farm Press. ISBN 978-0-910746-98-4.

- ^ Karnoutsos, Carmela (2007). "Peach Tree War". Jersey City A to Z. New Jersey City University. Retrieved 17 February 20136.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Berthold Fernow; Edmund Bailey O'Callaghan (1881). Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York: new ser., v. 2 . Documents relating to the history and settlements of the towns along the Hudson and Mohawk rivers (with the exception of Albany), from 1630 to 1684, 1881. Weed, Parsons, Printers.

- ^ Karnoutsos, Carmela (2007). "350th Anniversary of the Dutch Settlement of Bergen Colonial Jersey City". Jersey City A to Z. New Jersey City University. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 52 (help) - ^ Laws and Ordinances of New Netherland, 1638-1674. Weed, Parsons and Company, printers. 1868.

- ^ "Old Bergen". GetNJ.com. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

Additional reading

- Cynthia J. Van Zandt (2008). Brothers Among Nations: The Pursuit of Intercultural Alliances in Early America 1580-1660. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518124-7.