Pince-nez

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2008) |

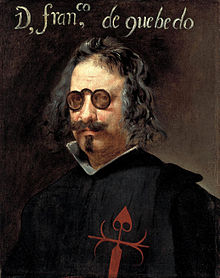

Pince-nez (/ˈpænsneɪ/ or /ˈpɪnsneɪ/;[1] French pronunciation: [pɛ̃sˈne]) is a style of glasses, popular in the 19th century, that are supported without earpieces, by pinching the bridge of the nose. The name comes from French pincer, "to pinch", and nez, "nose".

Although pince-nez were used in Europe in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, modern ones appeared in the 1840s and reached their peak popularity around 1880 to 1900.

Varieties

- Hard bridge – Also known as the fingerpiece, these have a solid bridge piece which is molded to fit the curvature of the bridge of the nose. They are anchored onto the bridge of the nose via two small spring-loaded clips terminating in special nose-pads made from bone or tortoise shell on metal called plaquettes, which are tweezered apart for placement on the face through applying pressure to two small lever-like finger-pieces located on the front of the bridge. Plaquettes could be either hinged and flexible, like modern spectacle nose-pads, permitting a better fit, or static as in the older examples of this type. This variety was manufactured as either a frame or as a two-piece mount for rimless. They were popular from the 1890s through to the 1950s, and were probably the most commonly seen variety during that time. Their popularity stemmed from the fact that they could be set and removed at will using only two fingers of one hand to operate the finger-pieces, which made them practical compared to other varieties which often required two hands to place the spectacles on the nose. Additionally they could sit comfortably on most nose bridges without having to be set at an angle to compensate for bone structure. However, because of the inflexibility of the bridge piece they had to be manufactured in a range of sizes for different width nose-bridges.

- C-bridge – These, as their name would suggest, possess a C-shaped bridge, which was composed of a curved, flexible piece of metal which would provide the tension needed to stay on the nose. This variety is the earliest style of true pince-nez. They existed from the 1820s through to the 1940s, and were available in a tremendous variety of styles – ranging from the early nose-padless type of the 19th century to the gutta-percha variety of the American Civil War era, and then on to the plaquette variety of the 20th century. Like the Hard bridge variety, this type was available either as a frame or as a two-piece mount for frameless glasses. Some of the earlier frames had cork nose-pads, as did some of the cheaper later ones, instead of plaquettes. The frames or bridge pieces could be gold or silver plated or made from stainless steel. The bridges were subject to constant wear and tear as they required repeated flexing when being set and removed from the face, so would frequently break or lose their tension. The advantage of this variety was that one size could fit a variety of nose bridges; however, often they had to be worn at an angle, especially if the wearer had a low forehead.

- Spring bridge – Also known as Astig, this variety consists of a sliding bar connecting the lenses which can be separated through a gentle pull. The bar is telescopic, consisting of two sliders within a tube-like spring, which provides the tension. The nose pads are usually cork and are attached directly to the frames. They can either be hinged or static. This variety was popular from the 1890s to the 1930s, after which they were seldom seen. They were created and marketed as 'sporting pince-nez', which were purportedly more difficult to jar from the face than the other varieties as well as being more comfortable to wear for longer periods. A major advantage was that one size could often fit a wide variety of nose shapes and sizes. This style was usually available only as a frame, with rimless examples being very difficult to find.[2]

Others

In this category are placed frames that should not be referred to as pince-nez, but resemble them in form and function.

- Oxford spectacles (or Oxfords for short) – The distinction between this style and pince-nez is not frequently drawn; often they are listed as a pince-nez when they are in fact a distinct style of spectacle. The style was developed in the 19th century when a professor at Oxford University accidentally broke off the handle from a pair of lorgnette spectacles. He reputedly affixed two small nose-pads to the frame and found that he could use the tension in the folding spring to perch them on his nose. Whether or not this story is apocryphal is unknown. Oxfords are undoubtedly descended from the lorgnette, as early examples of them often had handles in addition to nose-pads. In style Oxfords are much like the C-bridge as the tension is provided by a flexible, sprung piece of metal; however, they also resemble the spring bridge, as the spring connects the two lenses and is distinct from the nose-pieces. Oxfords were popular up until the 1930s, and were manufactured as both frames and as 4 piece mounts for frameless, although the latter are hard to find.

- Nose spectacles – These were developed in the 15th century as amongst the first practical vision correction aids, and could be seen up until the 18th century. They consisted of simple frames made of wood or metal; they could not be flexed or adjusted, instead having to be 'slotted' onto the bridge of the nose. They were designed for long sightedness, as reading lenses were the only ones that could be manufactured at that time. Original examples of nose spectacles are exceedingly hard to find in good condition today, and command large sums as collectors' pieces whenever they come onto the market.

Retention methods

Pince-nez spectacles were worn by both men and women. Since they can be uncomfortable to wear for extended periods if the wrong bridge size is chosen, and also because the constant wearing of glasses was out of fashion at the time, pince-nez were often suspended from a ribbon or chain worn around the neck, tied to the buttonhole of a lapel, or attached to a special ear-mount or to a hair-pin. Women often used a special brooch-like device pinned to the clothing, which would automatically retract the line to which the glasses were attached when they were not in use.

Use in early air combat

During the earliest era of air combat in World War I, a small number of frontline German fighter pilots serving with what would become known as the Luftstreitkräfte wore hard bridge pince-nez frames for their corrective lenses, including the very first pilot to defeat an opposing aircraft (on July 1, 1915) using a synchronized machine-gun armed aircraft, Leutnant Kurt Wintgens.[citation needed]

In popular culture

Pince-nez is central to the murder mystery in the Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez. Another murder mystery, Whose Body? by Dorothy L. Sayers, features a victim found dead in a bathtub wearing nothing but a pair of pince-nez.

Numerous fictional characters have been depicted as wearing pince-nez. These include Hercule Poirot in the television series Agatha Christie's Poirot, who wears pince-nez that is attached to a cord around his neck;[3] Morpheus in the Matrix film trilogy, who wears reflective-lensed pince-nez sunglasses when he appears in The Matrix;[4] Walt Disney's cartoon character Scrooge McDuck; Professor Frost in the C. S. Lewis novel That Hideous Strength, who is identified multiple times by his wearing a pair of pince-nez; and Koroviev/Fagott, a member of Satan's entourage in Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Pince-nez" Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House. Accessed: January 10, 2008

- ^ "Photo of Spring bridge pince-nez". Perret opticians. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ "David Suchet reveals the secret to Poirot's "rapid, mincing" walk". Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ^ "The End of Humanism". Retrieved 2013-11-13.

External links

Media related to Pince-nez at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pince-nez at Wikimedia Commons