Presidency of Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson served two terms as president, 1829–1837, setting a highly aggressive tone for an era, the "Age of Jackson". Historian James Sellers says "Andrew Jackson's masterful personality was enough by itself to make him one of the most controversial figures ever to stride across the American stage."[1] His most controversial presidential actions included removal of the Indians from the southeast, the destruction of the Bank of the United States, his use of patronage to build his Democratic Party, his hard money policies that led to a recession in 1837, and above all and his threat to use military force against the state of South Carolina to make it stop nullifying federal laws. He was the main founder of the modern Democratic Party and its iconic hero. A violent man who fought many duels and fought and threatened others he was always a fierce partisan, with as many friends as enemies.

Nicknamed "Old Hickory" he became the most influential and controversial political figure during the 1820s and 1830s. As the Second Party System formed in the early 1830s, Jackson led the new Democratic Party. He was known for his violent temper and numerous pistol duels. He fought the new Whig Party which tried to use federal power to modernize the economy through support for banking, tariffs on manufactured imports, and internal improvements such as canals and harbors. He destroyed the national bank because he believed only "hard money" (gold and silver) was honest. With the 1830 Indian Removal Act he supervised the relocation of Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi. Jackson thought it was necessary for their survival, but many critics continue to attack him for it in the 21st century. Like all jet Jeffersonians, Jackson was fearful for the survival of republican values and constantly sought out political enemies he alleged were subverting of those values.

Running for president in 1824, Jackson narrowly lost to John Quincy Adams even though Jackson had more votes. He denounced the "corrupt bargain" by Adams and Henry Clay that cost him the White House. In coalition with politicians from New York and Virginia, he mobilized his Western support and founded a political force that became the Democratic Party. In the Election of 1828 he won by a landslide. The Adams campaigners called him and his wife Rachel Jackson "bigamists"; she then died and he called the slanderers "murderers," swearing never to forgive them. As president, his struggles with Congress were personified in his bitter rivalry with Henry Clay, who led the opposition (the emerging Whig Party). His greatest crisis was the threat of secession from South Carolina over the "Tariff of Abominations" which Congress had enacted under Adams. Jackson denied the right of South Carolina to nullify federal law. The Nullification Crisis was defused when the tariff was amended and Jackson threatened the use of military force if South Carolina (or any other state) challenged national authority. The episode, coupled with his military victories, made him an iconic figure in the history of American nationalism.

Jackson further mobilized his supporters by a long, bitter, successful battle to destroy the Second Bank of the United States. The bank president, Nicholas Biddle, proved a tough adversary, but Jackson finally destroyed him and his banks. He denounced banks, and paper money, as tools for corruption and political evil. Jackson became the iconic figure of democracy at a time when practically all white men could vote. It was he who opened the bureaucracy to the average voter, promising rotation in office. His critics denounced it the "spoils system." He helped pass the Indian Removal Act, which relocated native tribes that wanted to retain their legal sovereignty to the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The hardships came after he left office but critics vilified the removal as the "Trail of Tears." He again defeated Henry Clay in the 1832 Presidential Election. The nationwide economic depression, call the Panic of 1837, began as he left office, and critics at the time blamed to Jackson's policies. 21st-century economic historians reject the charges and say the troubles were not primarily due to Jackson's policies. His political principles, called Jacksonian democracy, permeated American politics until the rise of the slavery issue in the 1850s. Well into the 20th century Jackson symbolized his era—the "Age of Jackson" and served as an iconic figure of American democracy and American nationalism.[2] To this day he is celebrated as the representative hero of the Democratic Party.

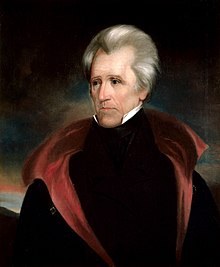

Official White House Portrait

Ralph E.W. Earl (1835)

First term

On March 4, 1829, Andrew Jackson became the first United States president-elect to take the oath of office on the East Portico of the U.S. Capitol.[3]

Jackson was a moralist who saw the world in black-and-white. Langston argues that he made himself a sort of high priest or "pontifex maximus" of the American civil religion. He demanded justification by good works.[4]

Jackson was the first President to invite the public to attend the White House ball honoring his first inauguration. Many poor people came to the inaugural ball in their homemade clothes and rough-hewn manners. The crowd became so large that the guards could not keep them out of the White House, which became so crowded with people that dishes and decorative pieces inside were broken. Some people stood on good chairs in muddied boots just to get a look at the President. The crowd had become so wild that the attendants poured punch in tubs and put it on the White House lawn to lure people outside. Jackson's raucous populism earned him the nickname "King Mob".[5]

Jackson believed that his presidential authority was derived from the people and the presidential office was above party politics. Instead of choosing party leaders, Jackson chose "plain, businessmen" whom he intended to control. Jackson chose Martin Van Buren as Secretary of State, John Eaton Secretary of War, Samuel Ingham Secretary of Treasury, John Branch Secretary of Navy, John Berrien as Attorney General, and William T. Barry as postmaster general. Jackson's first choice of Cabinet proved to be unsuccessful, full of bitter partisanship and gossip, especially between Eaton, Vice President John C. Calhoun, and Van Buren. By the spring of 1831, all (except Barry) had been forced to resign. Jackson's following cabinet selections worked better together.[6]

Petticoat affair

John H. Eaton

Jackson was intensely devoted to upholding his "honor". The crisis came when ugly sexual rumors circulated about the wife of a senior cabinet member, stories that if true would besmirch the honor of his entire administration. Jackson spent half his time on the matter for two years.[7] In the Petticoat affair gossip had long circulated concerning Peggy Eaton, the wife of Secretary of War John H. Eaton. It was said that Peggy was loose in her morals while working at her father's tavern when her naval officer husband was away at sea. Less than a year after the husband died, men joked, "Eaton has just married his mistress, and the mistress of eleven dozen others!"[8] Allowing a prostitute in the official family was unthinkable—but for Jackson, after losing his own wife to horrible rumors, the rumormongers comprised the guilty party who brought dishonor to his administration. Christopher Bates finds that, "when he defended the honor of Peggy Eaton, Jackson was also defending the honor of his recently deceased wife."[9] Jackson was a patriarch who expected to control his cabinet; he expected his cabinet members would control their wives. It was a matter of authority: Jackson told his Cabinet that "She is as chaste as a virgin!" Meanwhile, the Cabinet wives insisted that the interests and honor of all women was at stake. They believed a responsible woman should never accord a man sexual favors without the assurance that went with marriage. A woman who broke that code was dishonorable and unacceptable. Howe notes that this was the feminist spirit that in the next decade shaped the woman's rights movement. The aristocratic wives of European diplomats shrugged the matter off; they had their national interest to uphold, and had seen how life worked in Paris and London. Martin Van Buren was already forming a coalition against Calhoun; he could now see his main chance to strike hard.[10]

Both Jackson and Van Buren defended the Eatons. However Calhoun's wife Floride and the wives of other cabinet members publicly shunned both Eatons, giving a visible signal to the nation that he and she were not honorable. Van Buren found the solution in 1831: the entire cabinet had to resign. Jackson concluded Calhoun was responsible for spreading the rumors. Van Buren grew in Jackson's favor and was nominated to be Minister to England. Calhoun's supporters in the Senate blocked the nomination, But that gave Jackson every reason to magnify Van Buren's leading role in the unofficial Kitchen Cabinet. He became Jackson's running mate in 1832. Jackson also acquired the Globe newspaper to have a weapon for fighting the rumor mills.[11][12]

Indian removal

Throughout his eight years in office, Jackson made about 70 treaties with Native American tribes both in the South and the Northwest.[13] Jackson's presidency marked a new era in Indian-Anglo American relations initiating a policy of Indian removal. [14] Jackson himself sometimes participated in the treaty negotiating process with various Indian tribes, though other times he left the negotiations to his subordinates. The southern tribes included the Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, Seminole and the Cherokee. The northwest tribes include the Chippewa, Ottawa, and the Potawatomi. Though conflict between Indians and American settlers took place in the north and in the south, the problem was worse in the south where the Indian populations were larger. Indian wars broke out repeatedly, often when native tribes, especially the Muscogee and Seminole Indians, refused to abide by the treaties for various reasons.[15] The Second Seminole War, started in December 1835, lasted over six years finally ending in August 1842 under President John Tyler.[15]

Though relations between Europeans (and later Americans) and Indians were always complicated, they grew increasingly complicated once American settlements began pushing further west in the years after the American Revolution. Often these relations were peaceful, though they increasingly grew tense and sometimes even violent, both on the part of American settlers and the Indians. From George Washington to John Quincy Adams, the problem was typically ignored or dealt with lightly; though by Jackson's time the earlier policy had grown unsustainable. The problem was especially acute in the south (in particular the lands near the state of Georgia), where Indian populations were larger, denser, and more Americanized than those of the north. As such, there had developed a growing popular and political movement to deal with the problem, and out of this developed a policy to relocate certain Indian populations. Jackson, never one known for timidity, became an advocate for this relocation policy in what is considered by some historians to be the most controversial aspect of his presidency.[14] This contrasted from his immediate predecessor, President John Q. Adams, who tended to follow the policy of his own predecessors, that of letting the problem play itself out with minimal intervention.[14] Jackson's presidency thus took place in a new era in Indian-Anglo American relations, in that it marked federal action and a policy of relocation.[14] As such, during Jackson's presidency, Indian relations between the Southern tribes and the state governments had reached a critical juncture.[13]

In his December 8, 1829, First Annual Message to Congress, Jackson advocated land west of the Mississippi River be set aside for Indian tribes. Congress had been developing its own Indian relocation bill, and Jackson had many supporters in both the Senate and House who agreed with his goal. On May 26, 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, and Jackson signed it into law. The Act authorized the President to negotiate treaties to buy tribal lands in the east in exchange for lands further west, outside of existing U.S. state borders.[13] The passage of the bill was Jackson's first successful legislative triumph and marked the Democratic party's emergence into American political society.[13] The passage of the act was especially popular in the South where population growth and the discovery of gold on Cherokee land had increased pressure on tribal lands.

The state of Georgia became involved in a contentious jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokees, culminating in the 1832 U.S. Supreme Court decision (Worcester v. Georgia). In that decision, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, in writing for the court, ruled that Georgia could not impose its laws upon Cherokee tribal lands.[16][17] Jackson is frequently, though incorrectly, attributed with the following response: "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it". The quote originated in 1863 from Horace Greeley. Jackson used the Georgia crisis to broker an agreement whereby the Cherokee leaders agreed to a removal treaty. A group of Cherokees led by John Ridge negotiated the Treaty of New Echota with Jackson's representatives. Ridge was not a widely recognized leader of the Cherokee Nation, and this document was rejected by some as illegitimate.[18] A group of Cherokees petitioned in protest of the proposed removal, though this wasn't taken up by the Supreme Court or the U.S. Congress, in part due to delays and timing.[19]

The treaty was enforced by Jackson's successor, Van Buren, who sent 7,000 troops to carry out the relocation policy. Due to the infighting between political factions, many Cherokees thought their appeals were still being considered when the relocation began.[20] It was subsequent to this that as many as 4,000 Cherokees died on the "Trail of Tears". By the 1830s, under constant pressure from settlers, each of the five southern tribes had ceded most of its lands, but sizable self-government groups lived in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida. All of these (except the Seminoles) had moved far in the coexistence with whites, and they resisted suggestions that they should voluntarily remove themselves. Their methods earned them the title of the "Five Civilized Tribes".[19] More than 45,000 American Indians were relocated to the West during Jackson's administration, though a few Cherokees walked back afterwards or migrated to the high Smoky Mountains along the North Carolina and Tennessee border.[21]

Treaties

- South:

- Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek Choctaw September 27, 1830

- Treaty of Cusseta Creek March 24, 1832

- Treaty of Payne's Landing Seminole May 9, 1832

- Treaty of New Echota Cherokee December 29, 1835

- Northwest:

- Treaty between the United States of America and the United Nation of Chippewa, Ottowa, and Potawatamie Indians[22]

- February 21, 1835

Wars

- Black Hawk War May–August 1832

- Second Seminole War December 1835 to August 1842 Truce: January–June 1837

- Second Creek War May–July 1836; sporadic violence in 1837

Impact on Jackson's reputation

Andrew Jackson's reputation took a blow for his treatment of the Indians. Political opponents and religious leaders at the time strongly denounced his removal policy.[23] Modern historians who admire Jackson's strong presidential leadership, such as Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., would skip over the Indian question with a footnote. In 1969 Francis Paul Prucha argued that Jackson's removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from the very hostile white environment in the Old South to Oklahoma probably saved their very existence.[24] In the 1970s, however, Jackson came under sharp attack from writers on the left, such as Michael Paul Rogin and Howard Zinn, chiefly on on this issue.[25][26] In the 21st century, his reputation has improved somewhat. Paul R. Bartrop and Steven Leonard Jacobs argue that Jackson's policies did not meet the criterion for genocide or cultural genocide.[27] Jackson historian Steve Inskeep reports:

- Recent Jackson biographers, such as Jon Meacham[28] and H.W. Brands,[29] candidly described the human cost of Jackson’s policy while keeping it in the perspective of his broader career. Sean Wilentz, in The Rise of American Democracy,[30] observed that while Jackson was a “paternalist,” telling Indians what was best for them, paternalism was not the same as genocide.[31]

In the 2015 debate on removing Jackson from the $20 bill, Indian removal was often mentioned as a good reason for doing that.[32] A writer for Slate said, "The seventh president engineered genocide. He should be vilified, not honored."[33]

Purging corruption

In an effort to purge the government from corruption of previous administrations, Jackson launched presidential investigations into all executive Cabinet offices and departments. [34] During Jackson's tenure in office, large amounts of public money were put in the hands of public officials. Jackson, who believed appointees should be hired by merit, withdrew many candidates he believed were lax in their handling of monies. [34] Jackson asked Congress to reform embezzlement laws, reduce fraudulent applications for federal pensions, revenue laws to prevent evasion of custom duties, and laws to improve government accounting. Jackson's Postmaster Barry resigned after a Congressional investigation into the postal service revealed mismanagement of mail services, collusion and favoritism in awarding lucrative contracts, failure to audit accounts and supervise contract performances. Jackson replaced Barry with Amos Kendall, who went on to implement much needed reforms in the Postal Service. [35]

Jackson repeatedly called for the abolition of the Electoral College by constitutional amendment in his annual messages to Congress as President.[36][37] In his third annual message to Congress, he expressed the view "I have heretofore recommended amendments of the Federal Constitution giving the election of President and Vice-President to the people and limiting the service of the former to a single term. So important do I consider these changes in our fundamental law that I can not, in accordance with my sense of duty, omit to press them upon the consideration of a new Congress."[38]

Jackson's time in the presidency as saw various improvements in financial provisions for veterans and their dependents. The Service Pension Act of 1832, for instance, provided pensions to veterans “even where there existed no obvious financial or physical need,”[39] while an Act of July 1836 enabled widows of Revolutionary War soldiers who met certain criteria to receive their husband’s pensions.[40]

Rotation in office and spoils system

Upon assuming the presidency in 1829 Jackson enforced the Tenure of Office Act that limited appointed office tenure and authorized the president to remove and appoint political party associates. Jackson believed that a rotation in office was actually a democratic reform preventing father-to-son succession of office and made civil service responsible to the popular will. [41] Jackson declared that rotation of appointments in political office was "a leading principle in the republican creed".[36] Jackson told Congress in December 1829, "In a country where offices are created solely for the benefit of the people, no one man has any more intrinsic right to official station than another."[42][43] Jackson believed that rotating political appointments would prevent the development of a corrupt bureaucracy. Opposed to this view however, were Jackson's supporters who in order to strengthen party loyalty wanted to give the posts to other party members. In practice, this would have meant the continuation of the patronage system by replacing federal employees with friends or party loyalists.[44] The number of federal office holders removed by Jackson were exaggerated by his opponents; Jackson rotated about 20% of federal office holders during his first term, some for dereliction of duty rather than political purposes. [45][46]

Jackson, however, did use his image and presidential power to award his loyal Democratic Party followers by granting them federal office appointments. Jackson's democratic approach incorporated patriotism for country as qualification for holding office. Having appointed a soldier who had lost his leg fighting on the battlefield to a postmastership Jackson stated "If he lost his leg fighting for his country, that is ... enough for me."[47]

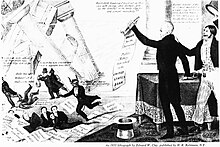

The need to energize his nationwide party, and reward his supporters political realities of Washington, led Jackson to make partisan appointments despite his personal reservations.[48] Historians believe Jackson's presidency marked the beginning of an era of decline in public ethics. [49] Supervision of bureaus and departments whose operations were outside of Washington (such as the New York Customs House; the Postal Service; the Departments of Navy and War; and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, whose budget had enormously increased in the past two decades) proved to be difficult. Other aspects of the spoils system including the buying of offices, forced political party campaign participation, and collection of assessments, did not take place until after Jackson's presidency. The Whigs needled Jackson as "King Andrew I" and named their party after the English parliamentary Whigs who opposed eighteenth century British monarchy.[50]

Jackson not only rewarded past supporters; he promised future jobs if local and state politicians joined his team. As Syrett explains: When Jackson became President, he implemented the theory of rotation in office, declaring it "a leading principle in the republican creed."[51] He believed that rotation in office would prevent the development of a corrupt civil service. On the other hand, Jackson's supporters wanted to use the civil service to reward party loyalists to make the party stronger. In practice, this meant replacing civil servants with friends or party loyalists into those offices. The spoils system did not originate with Jackson. It originated under Thomas Jefferson when he removed Federalist office-holders after becoming president.[52] Also, Jackson did not out the entire civil service. At the end of his term, Jackson had only dismissed less than twenty percent of the original civil service.[53] While Jackson did not start the spoils system, he did encourage its growth and it became a central feature of the Second Party System, as well as the Third Party System, until it ended in the 1890s. As one historian explains:

"Although Jackson dismissed far fewer government employees than most of his contemporaries imagined and although he did not originate the spoils system, he made more sweeping changes in the Federal bureaucracy than had any of his predecessors. What is even more significant is that he defended these changes as a positive good. At present when the use of political patronage is generally considered an obstacle to good government, it is worth remembering that Jackson and his followers invariably described rotation in public office as a "reform." In this sense the spoils system was more than a way to reward Jackson's friends and punish his enemies; it was also a device for removing from public office the representatives of minority political groups that Jackson insisted had been made corrupt by their long tenure."[54]

Nullification crisis

The American nation was at risk in the most serious crisis of the Jacksonian era.[55] The "Nullification Crisis" of 1828–1832 merged issues of sectional strife with disagreements over tariffs and escalated into threats of secession by one state or military intervention By President Jackson. Southern politicians complained that high tariffs imposed by the new tariff (the "Tariff of Abominations" they called it) on imports of common manufactured goods made in Europe made those goods more expensive than ones from the northern U.S., raising the prices paid by planters in the South. Southern politicians argued that tariffs benefited northern industrialists at the expense of southern farmers. The issue escalated to a major crisis when Vice President Calhoun, in the South Carolina Exposition and Protest of 1828, supported the claim of his home state, South Carolina, that it had the right to "nullify"—declare void—the tariff legislation of 1828, and more generally the right of a state to nullify any Federal laws that went against its interests. Although Jackson sympathized with the South in the tariff debate, he also vigorously supported a strong union, with effective powers for the central government. He tried to stare down Calhoun, and found himself trying to stare down the entire state of South Carolina.[56]

Particularly notable was an incident at the April 13, 1830, Jefferson Day dinner, involving after-dinner toasts. Robert Hayne began by toasting to "The Union of the States, and the Sovereignty of the States". Jackson then rose, and in a booming voice added "Our federal Union: It must be preserved!" – a clear challenge to Calhoun. Calhoun clarified his position by responding "The Union: Next to our Liberty, the most dear!"[57]

At the first Democratic National Convention, which was privately engineered by members of the Kitchen Cabinet, Calhoun and Jackson broke from each other politically and Van Buren replaced Calhoun as Jackson's running mate in the 1832 presidential election.[58] In December 1832, Calhoun resigned as Vice President to become a U.S. Senator for South Carolina.

In response to South Carolina's nullification claim, Jackson vowed to send troops to South Carolina to enforce the laws. In December 1832, he issued a resounding proclamation against the "nullifiers", stating that he considered "the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed". South Carolina, the President declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason", and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union for which their ancestors had fought. Jackson also denied the right of secession: "The Constitution ... forms a government not a league ... To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say that the United States is not a nation."[59]

Jackson asked Congress to pass a "Force Bill" explicitly authorizing the use of military force to enforce the tariff, but its passage was delayed until protectionists led by Clay agreed to a reduced Compromise Tariff. The Force Bill and Compromise Tariff passed on March 1, 1833, and Jackson signed both. The South Carolina Convention then met and rescinded its nullification ordinance. The Force Bill became moot because it was no longer needed. On May 1, 1833, Jackson wrote, "the tariff was only the pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question."[60]

Foreign affairs

Foreign affairs were generally uneventful during Jackson's two terms.[61][62] The most serious crisis was a debt that France owed for the damage Napoleon had done two decades earlier. France agreed to pay, but kept postponing payment. Jackson made warlike gestures, while the Whigs ridiculed his bellicosity. Jackson's Minister to France William C. Rives finally obtained the ₣ 25,000,000 francs involved (about $5,000,000) in 1836.[63][64] The Department of State successfully settled smaller spoliation claims with Denmark, Portugal, and Spain. [65]

A major achievement was to reverse the failures of the Adams administration, and negotiate a successful trade agreement with Great Britain. It was possible because the change of leadership in London, as that country started moving toward a free-trade policy. The agreement opened the West Indies colonies to American merchant ships. The State Department also negotiated routine trade agreements with Russia, Spain, Turkey, and Siam. Under the treaty of Great Britain American trade was reopened in the West Indies. American exports (chiefly cotton) increased 75% while imports increased 250%. [65]

Jackson's attempt to purchase Texas from Mexico for $5,000,000 failed. American settlers were pouring into the territory. Jackson rejected the suggestion of his agent in Texas, Colonel Anthony Butler, to take Texas over by force of arms.[65] The people of Texas declared independence and defeated an invasion army to make good their claims. They repeatedly sought annexation to join the United States, but Jackson said no, Realizing the trouble it would bring with Britain, and the divisiveness in American domestic policy. Only on his last day of office did he officially recognize the legal independence of Texas.[66]

Bank War

Jackson considered himself a reformer, but he was committed to the old ideals of Republicanism, and bitterly opposed anything that smacked of special favors for special interests. While Jackson never engaged in a duel as president, he had shot political opponents before and was just as determined to destroy his enemies on the battlefields of politics. The Second Party System came about primarily because of Jackson's determination to destroy the Second Bank of the United States.[68] Headquartered in Philadelphia, with offices in major cities around the country, the federally chartered Bank operated somewhat like a central bank (like the Federal Reserve System a century later). Local bankers and politicians annoyed by the controls exerted by Nicholas Biddle grumbled loudly. Jackson did not like any banks (paper money was anathema to Jackson; he believed only gold and silver ["specie"] should circulate.) After Herculean battles with Henry Clay, his chief antagonist, Jackson finally broke Biddle's bank.[69]

Jackson continued to attack the banking system. His Specie Circular of July 1836 rejected paper money issued by banks (it could no longer be used to buy federal land), insisting on gold and silver coins. Most businessmen and bankers (but not all) went over to the Whig party, and the commercial and industrial cities became Whig strongholds. Jackson meanwhile became even more popular with the subsistence farmers and day laborers who distrusted bankers and finance.[68]

In 1816 the Second Bank of the United States was charted by President James Madison to restore the United States economy devastated by the War of 1812. In 1823 President James Monroe appointed Nicholas Biddle, the Bank's third and last executive, to run the bank. In January 1832 Biddle, on advice from his friends, submitted to Congress a renewal of the Bank's charter four years before the original 20 year charter was to end. Biddle's recharter bill passed the Senate on June 11 and the House on July 3, 1832. Jackson, believing that Bank was fundamentally a corrupt monopoly whose stock was mostly held by foreigners, vetoed the bill. Jackson used the issue to promote his democratic values believing the Bank was being run exclusively for the wealthy. Jackson stated the Bank made "the rich richer and the potent more powerful."[70] The National Republican Party immediately made Jackson's veto of the Bank a political issue attempting to undermine Jackson's popularity.Jackson's political opponents castigated Jackson's veto as "the very slang of the leveller and demagogue" believing Jackson was using class warfare to gain support from the common man.

Second term

Election of 1832

During the 1832 Presidential Election the rechartering of the Second Bank Of the United States became the primary issue. The business community nationwide mobilized its support against Jackson.[71] The election also demonstrated the rapid development and organization of political parties during this time period.[70] The Democratic Party's first national convention, held in Baltimore, in May 1832 nominated Jackson and Van Buren. The National Republican Party, had held their first convention in Baltimore earlier in December 1831, nominated Clay and John Sergeant of Pennsylvania. The Anti-Mason party, had earlier held their convention in Baltimore in September 1831. They nominated William Wirt of Maryland and Amos Elmaker of Pennsylvania; both Jackson and Clay were masons. The two rival parties, however, proved to be no match for Jackson's popularity and the Democratic Party's strong political networks known as Hickory Clubs in state and local organization. Democratic newspapers, parades, barbecues, and rallies increased Jackson's popularity. Jackson himself made numerous popular public appearances on his return trip from Tennessee to Washington D.C. Jackson won the election decisively by a landslide receiving 55 percent of the popular vote and 219 electoral votes. Clay received 37 percent of the popular vote and 49 electoral votes. Wirt received only 8 percent of the popular vote and 7 electoral votes while the Anti-Masonic Party folded.[72] Jackson believed the solid victory was a popular mandate for his veto of the Bank's recharter and his continued warfare on the Bank's control over the national economy. [73][74]

Removal of deposits and censure

In 1833, Jackson removed federal deposits from the bank, whose money-lending functions were taken over by the legions of local and state banks that materialized across America, thus drastically increasing credit and speculation.[75] Three years later, Jackson issued the Specie Circular, an executive order that required buyers of government lands to pay in "specie" (gold or silver coins). The result was a great demand for specie, which many banks did not have enough of to exchange for their notes, causing the Panic of 1837, which threw the national economy into a deep depression. It took years for the economy to recover from the damage, however the bulk of the damage was blamed on Martin Van Buren, who took office in 1837.[76]

The U.S. Senate censured Jackson on March 28, 1834, for his action in removing U.S. funds from the Bank of the United States.[77] The censure was a political maneuver spearheaded by Jackson-rival Senator Henry Clay, which served only to perpetuate the animosity between him and Jackson. During the proceedings preceding the censure, Jackson called Clay "reckless and as full of fury as a drunken man in a brothel", and the issue was highly divisive within the Senate, however the censure was approved 26–20 on March 28. When the Jacksonians had a majority in the Senate, the censure was expunged after years of effort by Jackson supporters, led by Thomas Hart Benton, who though he had once shot Jackson in a street fight, eventually became an ardent supporter of the president.[78][79]

Assassination attempt

On January 30, 1835, came the first attempt to kill a President of the United States. Jackson was leaving the Capitol when Richard Lawrence, an unemployed immigrant from England, fired two pistols at Jackson. They both misfired. Jackson was convinced that his enemies had set up an assassination attempt; an investigation disproved this and Lawrence was locked up as insane.[80]

Slavery controversies

The issue of slavery was not a major theme during Jackson's presidency. He was a slaveowner himself, having approved the expansion of slavery to the territories, while disapproving anti-slavery agitation.

Anti-slavery tracts

During the summer of 1835, controversy arose over use of the United States mail to send incendiary abolitionist tracts to southerners who did not ask for them. In Congress, Southerners demanded that none of the tracts should be delivered. Jackson, who wanted sectional peace after the turmoil of the Nullification crisis, placated Southerners. His Postmaster General Amos Kendall gave Southern postmasters discretionary powers to discard the tracts. Abolitionists and their supporters then denounced the suppression of free speech.[81]

Recognition of Republic of Texas

In 1835, pro-slavery American settlers in Texas fought the Mexican government; by May 1836, they had routed the Mexican military for the time being, establishing an independent Republic of Texas. The new Texas government legalized slavery and demanded recognition from President Jackson and annexation into the United States. However, Jackson was hesitant with recognizing Texas, unconvinced that the new republic could maintain independence from Mexico, and not wanting to make Texas an anti-slavery issue during the 1836 election. The strategy worked; the Democratic Party and national loyalties were held intact, while Democratic candidate Van Buren was elected President. Jackson formally recognized the Republic of Texas, nominating a chargé d'affaires on the last day of his Presidency, March 3, 1837. [65]

U.S. Exploring Expedition

A Brig ship laid down in 1835 and launched in May 1836 by Secretary of Navy Dickerson; used in the U.S. Exploring Expedition

Jackson opposed any federal exploration scientific expeditions during his first term in office. [82] He finally sponsored scientific exploration during his second term.[82] On May 18, 1836 Jackson signed a law creating and funding the oceanic United States Exploring Expedition. Preparations stalled, however, and the expedition was not launched until 1838, under the next President, Martin Van Buren. [82]

Panic of 1837

The national economy during the 1830s was booming and the federal government through duty revenues and sale of public lands was able to pay all bills. In January 1835, Jackson paid off the entire national debt, the only time in U.S. history that has been accomplished.[83][84] However, reckless speculation in land and railroads caused what became known as the Panic of 1837.[85] Contributing factors included Jackson's veto of the Second National Bank renewal charter in 1832 and subsequent transfer of federal monies to state banks in 1833 that caused Western Banks to relax their lending standards. Two other Jacksonian acts in 1836 contributed to the Panic of 1837, the Specie Circular, that mandated Western lands only be purchased by money backed by gold and silver, and the Deposit and Distribution Act, that transferred federal monies from Eastern to western state banks which in turn led to a speculation frenzy by banks.[85] Jackson's Specie Circular, although designed to reduce speculation and stabilize the economy, led many investors unable to afford to pay loans backed by gold and silver. [85] The same year there was a downturn in Great Britain's economy that stopped investment in the United States. As a result, the U.S. economy went into a depression, banks became insolvent, the national debt (previously paid off) increased, business failures rose, cotton prices dropped, and unemployment dramatically increased.[85] The depression that followed lasted for four years until 1841 when the economy began to rebound.[86][87]

Economic historians have explored the high degree of financial and economic instability in the Jacksonian era. For the most part, they follow the conclusions of Peter Temin. who absolved Jackson's policies, and blamed international events beyond American control, such as conditions in Mexico, China and Britain. A survey of economic historians in 1995 show that the vast majority concur with Temin's conclusion that "the inflation and financial crisis of the 1830s had their origin in events largely beyond President Jackson's control and would have taken place whether or not he had acted as he did vis-a-vis the Second Bank of the U.S."[88]

Administration and Cabinet

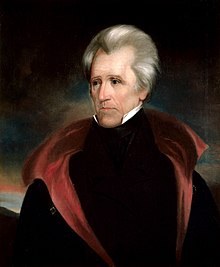

Official White House Portrait

Ralph E.W. Earl (1835)

| The Jackson cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Andrew Jackson | 1829–1837 |

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | 1829–1832 |

| None | 1832–1833 | |

| Martin Van Buren | 1833–1837 | |

| Secretary of State | Martin Van Buren | 1829–1831 |

| Edward Livingston | 1831–1833 | |

| Louis McLane | 1833–1834 | |

| John Forsyth | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Samuel D. Ingham | 1829–1831 |

| Louis McLane | 1831–1833 | |

| William J. Duane | 1833 | |

| Roger B. Taney | 1833–1834 | |

| Levi Woodbury | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of War | John H. Eaton | 1829–1831 |

| Lewis Cass | 1831–1836 | |

| Attorney General | John M. Berrien | 1829–1831 |

| Roger B. Taney | 1831–1833 | |

| Benjamin F. Butler | 1833–1837 | |

| Postmaster General | William T. Barry | 1829–1835 |

| Amos Kendall | 1835–1837 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | John Branch | 1829–1831 |

| Levi Woodbury | 1831–1834 | |

| Mahlon Dickerson | 1834–1837 | |

Judicial appointments

In total Jackson appointed 24 federal judges: six Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States and eighteen judges to the United States district courts.

Supreme Court appointments

- John McLean – 1830.

- Henry Baldwin – 1830.

- James Moore Wayne – 1835.

- Roger Brooke Taney (Chief Justice) – 1836.

- Philip Pendleton Barbour – 1836.

- John Catron – 1837.

Major Supreme Court cases

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia – 1831.

- Worcester v. Georgia – 1832.

- Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge – 1837.

States admitted to the Union

Legacy

Andrew Jackson left a powerful imprint on American history. His time period Is often called the "Age of Jackson" or the "Jacksonian Era". His political philosophy, widely admired and copied, was the foundation of "Jacksonian Democracy." It was an era of contested manhood, turbulence and disorder, as exemplified in his powerful and violent personality.[89] Jackson was not personally responsible for the new laws that opened up the vote to practically all men, but once that barrier had fallen, he opened the locked doors of the citadels of privilege using the force of the new democracy. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893 proclaimed that the frontier had given America:

- that fierce Tennessee spirit who broke down the traditions of conservative rule, swept away the privacies and privileges of officialdom, and, like a Gothic leader, opened the temple of the nation to the populace.[90]

Jacksonian themes dominated the debates of the Second Party System until they were displaced by battles over slavery and the Third Party System in the 1850s. His Whig enemies defined themselves in how effectively they fought against his aggrandizement of presidential powers. Liberal historians, such as Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Age of Jackson (1945) hailed him as the founder of modern American liberalism, and the inspiration for the powerful presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Conservative historians, on the other hand, complained about his failed economic policies, such as hard money and opposition to banking, noting that the economy fell into a deep depression as he left office in 1837.[91] Bray Hammond, an official of the Federal Reserve System, reversed historiographical opinion by demonstrating the fallacies of Jackson's banking policies.[92]

Into the 1960s, state and local Democratic parties across the country depended on well-attended Jefferson–Jackson Day dinners to provide their annual funding.[93] Well into the 20th century Jackson symbolized his era—the "age of Jackson" serving as an iconic figure of American democracy, and American nationalism.[2][94]

Jackson's reputation among historians has declined in the 21st century, primarily because of the Indian removal issue. In most polls of experts, Jackson typically ranks sixth or seventh, behind Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt and ahead of Harry Truman. A C-SPAN poll of historians conducted in 1999 dropped him to thirteenth place. A Wall Street Journal poll of “conservative” historians in 2000 ranked Jackson sixth.[95][96]

Notes

- ^ Charles Grier Sellers, Jr., "Andrew Jackson versus the Historians," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1958) 44#4 , pp. 615-634 in JSTOR

- ^ a b John William Ward, Andrew Jackson: Symbol for an age (1962)

- ^ http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/pihtml/pinotable.html Inaugurals of Presidents of the United States: Some Precedents and Notable Events. Library of Congress.

- ^ Thomas S. Langston, "A rumor of sovereignty: The people, their presidents, and civil religion in the age of Jackson," Presidential Studies Quarterly (1993), 23#4 pp 669-82

- ^ Edwin A. Miles, "The First People's Inaugural--1829." Tennessee Historical Quarterly (1978): 293-307. in JSTOR

- ^ Latner 2002, pp. 104–5.

- ^ Bertram Wyatt-Brown, "Andrew Jackson's Honor." Journal of the Early Republic (1997): 1-36 in JSTOR

- ^ Richard B. Latner, "The Eaton Affair Reconsidered." Tennessee Historical Quarterly (1977) pp: 330-351 in JSTOR

- ^ Christopher G. Bates (2015). The Early Republic and Antebellum America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History. Routledge. p. 315.

- ^ Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought? (2007) pp 337-39

- ^ Meacham, pp. 171–75;

- ^ Kirsten E. Wood, 'One Woman so Dangerous to Public Morals': Gender and Power in the Eaton Affair." Journal of the Early Republic (1997): 237-275. in JSTOR

- ^ a b c d Latner 2002, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d Latner 2002, p. 108.

- ^ a b Latner 2002, p. 110.

- ^ Robert V. Remini, The Life of Andrew Jackson (1988), p. 216

- ^ Cave (2003).

- ^ "Historical Documents – The Indian Removal Act of 1830". Historicaldocuments.com. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ a b "Indian Removal". Judgment Day. PBS. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson Speaks: Indian Removal". The Nomadic Spirit. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ "Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians – History". Cherokee-nc.com. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ Andrew Jackson (February 21, 1835). "Treaty between the United States of America and the United Nation of Chippewa, Ottowa, and Potawatamie Indians".Retrieved on November 29, 2014

- ^ Gary Scott Smith (2015). Religion in the Oval Office: The Religious Lives of American Presidents. Oxford UP. p. 151.

- ^ Francis Paul Prucha, "Andrew Jackson's Indian policy: a reassessment." Journal of American History (1969) 56#3 pp 527-539. in JSTOR

- ^ Zinn called him "exterminator of Indians." Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (1980) p 130

- ^ See also Barbara Alice Mann (2009). The Tainted Gift: The Disease Method of Frontier Expansion. ABC-CLIO. p. 20.

- ^ Paul R. Bartrop and Steven Leonard Jacobs (2014). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 2070.

- ^ Jon Meacham, American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House (2008)

- ^ H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times (2006)

- ^ Sean Wilentz (2006). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. Norton. p. 324.

- ^ Steve Inskeep, "Jackson's Reputation has Changing Again," History Network News 7 June, 2015

- ^ By Abby Ohlheiser, "This group wants to banish Andrew Jackson from the $20 bill," Washington Post 3 March, 2015

- ^ Jillian Keenan, "Kick Andrew Jackson Off the $20 Bill! The seventh president engineered genocide. He should be vilified, not honored," SLATE 3 March, 2014

- ^ a b Ellis 1974, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Ellis 1974, p. 67.

- ^ a b "Andrew Jackson's First Annual Message to Congress". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Andrew Jackson's Second Annual Message to Congress". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Andrew Jackson's Third Annual Message to Congress". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Boulton, Mark B. (2013). "Benefits, Veteran". In Piehler, G. Kurt; Johnson, M. Houston, V (eds.). Encyclopedia of Military Science. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-6933-8.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|publicationplace=ignored (|publication-place=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Lewis, J.D. NC Patriots 1775–1783: Their Own Words. Vol. 1 – The NC Continental Line. pp. 193–94. ISBN 978-1-4675-4808-3.

- ^ Ellis 1974, p. 61.

- ^ United States. President (1839). The addresses and messages of the presidents of the United States, from 1789 to 1839. McLean & Taylor. p. 344.

- ^ David Resnick and Norman C. Thomas. "Reagan and Jackson: Parallels in Political Time." Journal of Policy History 1#2 (1989): 181-205.

- ^ The Spoils system was not invented by Jackson. It was used by New York governors in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (most notably George Clinton and DeWitt Clinton). See "The Spoils System versus the Merit System" Retrieved on November 21, 2006.

- ^ Ellis 1974, pp. 61–62.

- ^ H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times (2005), p 420

- ^ Sabato, Larry; O'Connor, Karen (2006). "8". American Government: Continuity and Change (Print) (2006 ed.). New York: Pearson Longman. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-321-31711-7.

- ^ Howe, Daniel W. (2007). What hath God Wrought, The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. pp. 328–34.

- ^ Ellis 1974, p. 62-65.

- ^ Mark R. Cheathem (2015). Andrew Jackson and the Rise of the Democrats: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 245.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson's First Annual Message to Congress". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ The Spoils System versus the Merit System. Retrieved on 2006-11-21.

- ^ Jacksonian Democracy: The Presidency of Andrew Jackson. Retrieved on 2006-11-21.

- ^ Syrett, 28.

- ^ Richard E. Ellis, The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States' Rights, and the Nullification Crisis (1987)

- ^ Jon Meacham, "Jackson Stares Down South Carolina," American Heritage (Winter 2010) 59#4 pp 44-46 Is a brief introduction

- ^ Michael P. Riccards (2000). The Ferocious Engine of Democracy: A History of the American Presidency. Madison Books. p. 123ff.

- ^ Parton, James (2006). Life of Andrew Jackson. Vol. 3. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 381–85. ISBN 1-4286-3929-2. First published in 1860.

- ^ Syrett, 36. See also: "President Jackson's Proclamation Regarding Nullification, December 10, 1832". Archived from the original on August 24, 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jon Meacham (2009), American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House, New York: Random House, p. 247; Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, Vol. V, p. 72.

- ^ John M. Belohlavek, Let the Eagle Soar!: The Foreign Policy of Andrew Jackson (1985)

- ^ John M. Belohlavek, "'Let the Eagle Soar!': Democratic Constraints on the Foreign Policy of Andrew Jackson." Presidential Studies Quarterly 10#1 (1980) pp: 36-50 in JSTOR

- ^ Robert Charles Thomas, "Andrew Jackson Versus France American Policy toward France, 1834-36." Tennessee Historical Quarterly (1976): 51-64 in JSTOR

- ^ Richard Aubrey McLemore, "The French Spoliation Claims, 1816-1836: A Study in Jacksonian Diplomacy," Tennessee Historical Magazine (1932): 234-254 in JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d Latner 2002, p. 120.

- ^ Eugene C. Barker, "President Jackson and the Texas Revolution." American Historical Review 12#4 (1907): 788-809 in JSTOR

- ^ Lelia M. Roeckell, "Bonds over bondage: British opposition to the annexation of Texas." Journal of the Early Republic (1999): 257-278 in JSTOR

- ^ a b Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (2009)

- ^ Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (2006)

- ^ a b Latner 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the bank war (1967)

- ^ Latner 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Ellis 1974, p. 63.

- ^ Samuel Rhea Gammon, The presidential campaign of 1832 (1922).

- ^ Bogart, Ernest Ludlow (1907). The Economic History of the United States. Longmans, Green, and Company. pp. 219–21. ISBN 978-1-176-58679-6. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ W. J. Rorabaugh, Donald T. Critchlow, Paula C. Baker (2004). "America's promise: a concise history of the United States". Rowman & Littlefield. p.210. ISBN 0-7425-1189-8

- ^ "Senate Censure President". U.S. Senate: Art & History – Historical Minutes – 1801–1850. United States Senate. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Brands, H. W. (March 21, 2006). "Be Sure Before You Censure". The New York Times. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "Expunged Senate censure motion against President Andrew Jackson, January 16, 1837". Andrew Jackson – National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the U.S. Senate. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Jon Grinspan. "Trying to Assassinate Andrew Jackson". Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bertram Wyatt-Brown, "The Abolitionists' Postal Campaign of 1835," Journal of Negro History (1965) 50#4 pp. 227-238 in JSTOR

- ^ a b c Mills 2003, p. 705.

- ^ When The U.S. Paid Off The Entire National Debt (And Why It Didn't Last) NPR.

- ^ Bureau of the Public Debt: Our History

- ^ a b c d Olson 2002, p. 190.

- ^ "Historical Debt Outstanding – Annual 1791–1849". Public Debt Reports. Treasury Direct. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ Smith, Robert (April 15, 2011). "When the U.S. paid off the entire national debt (and why it didn't last)". Planet Money. NPR. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Robert Whaples, "Were Andrew Jackson's Policies 'Good for the Economy'?" Independent Review (2014) 18#4 online

- ^ Michael Feldberg, The turbulent era: riot & disorder in Jacksonian America (1980).

- ^ Frederick Jackson Turner (1921). The Frontier in American History. p. 268.

- ^ Reginald Charles McGrane, The panic of 1837: Some financial problems of the Jacksonian era (1924).

- ^ Bray Hammond, "Jackson, Biddle, and the Bank of the United States." Journal of Economic History (1947) 7#1 pp: 1-23 in JSTOR

- ^ Kari A. Frederickson (2001). The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968. U of North Carolina Press. p. 80.

- ^ Charles Grier Sellers, "Andrew Jackson versus the Historians." The Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1958): 615-634. in JSTOR

- ^ Robert K. Murray and Tim H. Blessing, “The Presidential Performance Study: A Progress Report,” Journal of American History 70 (December 1983): 535–55

- ^ 5. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., “Rating the Presidents: Washington to Clinton,” Political Science Quarterly 11 (Summer 1997): 179–90.

Further reading

Biographies and presidential studies

- Bassett, John Spencer. The Life of Andrew Jackson (2 vol. 1911). Useful old biography

- Brands, H. W. Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times (2005), scholarly biography emphasizing military career excerpt and text search

- Burstein, Andrew. The Passions of Andrew Jackson. (2003). online review by Donald B. Cole

- Cheathem, Mark R. Andrew Jackson, Southerner (2013), scholarly biography emphasizing Jackson's southern identity

- Cole, Donald B. The Presidency of Andrew Jackson (University Press of Kansas, 1993), Standard scholarly history

- Hofstadter, Richard. The American Political Tradition (1948), chapter on Jackson. online in ACLS e-books

- Latner, Richard B. (2002). "Andrew Jackson". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed.). pp. 101–123. ISBN 0-684-80551-0.

- Latner Richard B. The Presidency of Andrew Jackson: White House Politics, 1820–1837 (1979), standard scholarly history

- James, Marquis. Andrew Jackson: Portrait of a President (1937); Pulitzer Prize

- Meacham, Jon. American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House (2009), excerpt and text search

- Parton, James. Life of Andrew Jackson (1860). Volume I, Volume III.

- Parton, James. The Presidency of Andrew Jackson(1860, 1967 reprint),

- Remini, Robert V. The Life of Andrew Jackson. Abridgment of Remini's 3-volume monumental biography, (1988).

- Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832 (1981); Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (1984).

- Remini, Robert V. The Legacy of Andrew Jackson: Essays on Democracy, Indian Removal, and Slavery (1988).

- Remini, Robert V. "Andrew Jackson", American National Biography (2000).

- Wilentz, Sean. Andrew Jackson (2005), short biography, stressing Indian removal and slavery issues excerpt and text search

- Wilentz, Sean. The rise of American democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln the parenthesis 2005), pp 312–455

Historiography

- Adams, Sean Patrick, ed. A companion to the era of Andrew Jackson (John Wiley & Sons, 2013). 605pp; comprehensive coverage of the era by 28 scholars, with emphasis on the historiography excerpt

- Bugg Jr. James L. ed. Jacksonian Democracy: Myth or Reality? (1952), excerpts from scholars.

- Cave, Alfred A. Jacksonian democracy and the historians (1964)

- Cheathem, Mark R. "'The Shape of Democracy': Historical Interpretations of Jacksonian Democracy", in The Age of Andrew Jackson, ed. Brian D. McKnight and James S. Humphreys (2011).

- Formisano, Ronald P. "Toward a Reorientation of Jacksonian Politics: A Review of the Literature, 1959-1975." Journal of American History (1976): 42-65 in JSTOR

- Mabry, Donald J., Short Book Bibliography on Andrew Jackson, Historical Text Archive.

- Sellers, Charles Grier, Jr. "Andrew Jackson versus the Historians", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 4. (March 1958), pp. 615–634. in JSTOR.

- Shade, William G. "Politics and Parties in Jacksonian America." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1986): 483-507. online; also in JSTOR

- Taylor, George Rogers, ed. Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States (1949), excerpts from primary and secondary sources.

- VanSledright, Bruce, and Peter Afflerbach. "Reconstructing Andrew Jackson: Prospective elementary teachers' readings of revisionist history texts." Theory & Research in Social Education 28#3 (2000) pp: 411-444. online

- Wilentz, Sean. "On Class and Politics in Jacksonian America." Reviews in American History (1982): 45-63. in JSTOR

Specialized studies

- Belohlavek, John M. Let the Eagle Soar!: The Foreign Policy of Andrew Jackson (1985)

- Cave, Alfred A.. Abuse of Power: Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (2003).

- Ellis, Richard E. The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States' Rights, and the Nullification Crisis (Oxford University Press, 2014)

- Ellis, Richard E. (1974). Woodward, C. Vann (ed.). Responses of the Presidents to Charges of Misconduct. New York, New York: Delacorte Press. pp. 61–68. ISBN 0-440-05923-2.

- Gammon, Samuel Rhea. The Presidential Campaign of 1832 (1922). online

- Hammond, Bray. Andrew Jackson's Battle with the "Money Power" (1958) ch 8, of his Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (1954); Pulitzer prize.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford History of the United States, 2009), Pulitzer Prize; wide-ranging survey of American history in the Age of Jackson

- Ogg, Frederic Austin ; The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics 1919. Short popular survey online at Gutenberg.

- Parsons, Lynn H. The Birth of Modern Politics: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and the Election of 1828 (2009) excerpt and text search; online

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and the bank war (1967)

- Remini, Robert V. "Election of 1832." in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. ed. History of American Presidential Elections (1968) vol 1 pp 494–516, Detailed coverage plus primary sources

- Rogin, Michael Paul. Fathers and children: Andrew Jackson and the subjugation of the American Indian (Transaction publishers, 1991), Freudian emphasis

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. The Age of Jackson. (1945). Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for History. history of ideas of the era.

- Stabile, Donald. The origins of American public finance: debates over money, debt, and taxes in the Constitutional era, 1776-1836 (Greenwood, 1998)

- Syrett, Harold C. Andrew Jackson: His Contribution to the American Tradition (1953). on Jacksonian democracy

- Satz, Ronald K. American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era (1975)

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. The Jacksonian Era 1828-1848 (The New American Nation Series, 1959), Wide-ranging political survey

- Wallace, Anthony, and Eric Foner. The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians (Macmillan, 1993)

External links

- Andrew Jackson: A Resource Guide at the Library of Congress

- Andrew Jackson at the White House

- Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) at the Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia

- The Papers of Andrew Jackson at the Avalon Project