Uterine prolapse

| Uterine prolapse | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pelvic organ prolapse, prolapse of the uterus (womb), female genital prolapse, uterine descensus |

| |

| Depiction of uterine prolapse in which the uterus descending into the vaginal canal, towards the opening of the vagina | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | Vaginal fullness, pain with sex, trouble urinating, urinary incontinence[1] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[2] |

| Types | 1st to 4th degree[1] |

| Risk factors | Pregnancy, childbirth, obesity, constipation, chronic cough[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on examination |

| Differential diagnosis | Vaginal cancer, a long cervix[1] |

| Treatment | Pelvic floor therapy, Pessary, surgery |

| Frequency | About 14% of women[3] |

Uterine prolapse is a form of pelvic organ prolapse in which the uterus and a portion of the upper vagina protrude into the vaginal canal and, in severe cases, through the opening of the vagina.[4] It is most often caused by injury or damage to structures that hold the uterus in place within the pelvic cavity.[2] Symptoms may include vaginal fullness, pain with sexual intercourse, difficulty urinating, and urinary incontinence.[4][1] Risk factors include older age, pregnancy, vaginal childbirth, obesity, chronic constipation, and chronic cough.[1] Prevalence, based on physical exam alone, is estimated to be approximately 14%.

Diagnosis is based on a symptom history and physical examination, including pelvic examination.[4] Preventive efforts include managing medical risk factors, such as chronic lung conditions, smoking cessation, and maintaining a healthy weight.[1] Management of mild cases of uterine prolapse include pelvic floor therapy and pessaries. More severe cases may require surgical intervention, including removal of the uterus or surgical fixation of the upper portion of the vagina to a nearby pelvic structure.[4] Outcomes following management are generally positive with reported improvement in quality of life.[5]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

While uterine prolapse is rarely life-threatening, the symptoms associated with uterine prolapse can have a significant impact on quality of life.[2] The severity of prolapse symptoms does not necessarily correlate with the degree of prolapse, and one may experience little to no bothersome symptoms with even advanced prolapse.[2][3] Additionally, different forms of pelvic organ prolapse often present with similar symptoms.[2]

Most women who experience pelvic organ prolapse do not have symptoms.[2] When symptoms are present, the most common and most specific symptoms for uterine prolapse—and organ prolapse in general—into the vagina are bulge symptoms, such as pelvic pressure, vaginal fullness, or a palpable vaginal bulge, and these symptoms are often more common and more severe if the prolapse reaches the vaginal hymen.[2][3] Urinary symptoms, such as uncontrollable loss of urine or difficulty urinating, may also be present.[3] Complete uterine prolapse in which the uterus protrudes through the vaginal hymen is known as procidentia.[6] In the absence of treatment, symptoms of procidentia may include purulent vaginal discharge, ulceration, and bleeding.[1][6] Complications of procidentia include urinary obstruction.[6]

People may also report sexual dysfunction symptoms, such as pain with sexual intercourse and decreased libido.[4][2] There is conflicting data concerning the effect of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function.[2][3] The severity of the symptoms associated with prolapse seems to have a negative effect on sexual activity and reported satisfaction. Mild or asymptomatic prolapse does not seem to be associated with sexual complaints while more symptomatic prolapse is associated with more negative sexual symptoms.[3]

Causes

[edit]Conditions that chronically increase the pressure within the abdomen can predispose people to uterine prolapse.[2][1][7] This includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obesity, chronic cough, straining due to chronic constipation, and repetitive heavy lifting.[2][7] Tobacco smoking has been found to be correlated to pelvic organ prolapse both due to the risk of developing lung conditions that lead to chronic cough or COPD as well as the negative effects of tobacco chemicals on connective tissue.[2]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

The uterus is normally held in place by the combined effort of pelvic floor muscles, various ligaments, pelvic fascia, and the vaginal wall.[2][6] The levator ani muscle plays the most significant role in pelvic organ support by acting as a basket that keeps the pelvic organs suspended.[2] The uterosacral ligaments are especially important in providing support to the uterus by attaching and holding the uterus, cervix, and upper vagina to the sacrum.[2][3]

Uterine prolapse occurs when there is a disruption to any of the structures mentioned above that help hold the uterus in place.[2][6] Weakening of the levator ani muscles can occur during vaginal childbirth, in which portions of the muscle can detach from the bony pelvis, or through age-related changes to musculature, and this can lead to a loss of support for the uterus.[2] Pregnancy, vaginal childbirth, or injury can also stretch and weaken the uterosacral ligaments, leading to poor suspension or positioning of the uterus so that it is no longer supported by pelvic floor muscles.[3] Problems with the vaginal wall, such as trauma or loss of smooth muscle support in the wall, can lead to the uterus collapsing downward due to a loss of support.[2] When the uterus prolapses, it also drags the upper portion of the vagina (the apical vagina) along with it due to its anatomic relationship with the apical vagina.[6]

Additionally, the pelvic musculature and connective tissues are estrogen sensitive and respond to changes in estrogen level.[2] Estrogen deficiency, which can occur during menopause, can affect the production of collagen that is needed to build connective tissue that makes up ligaments and fascia, which can contribute to uterine prolapse.[2] This is also a reason that connective tissue disorders can predispose certain people to uterine prolapse.[2]

Diagnosis and management

[edit]Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of uterine prolapse is based on a history of symptoms, which may include symptom questionnaires, and a physical exam.[1][2] Usually, the physical exam involves a vaginal exam, often with a speculum, and a pelvic exam.[2][6] The extent and severity of prolapse is commonly documented using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system.[1][2]

Management

[edit]The management of uterine prolapse may be conservative or surgical, depending on factors such as personal preference, symptom severity, and extent of prolapse.[2] Additionally, management of existing medical conditions that can contribute to prolapse, such as chronic lung conditions or obesity, are important to prevent progression of uterine prolapse and reduce symptom burden.[6]

Conservative

[edit]

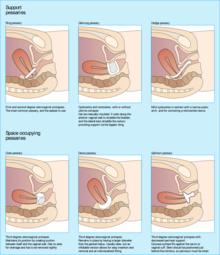

Conservative options include pelvic floor muscle strengthening exercises and pessaries.[6][2] Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), also known as Kegel exercise, has been found to improve the bulk and urinary symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse and improve quality of life when performed consistently and correctly.[2][8] Pessaries are a mechanical treatment that supports the vagina and elevates the prolapsed uterus to its anatomically correct position.[9] Pessaries are frequently offered as a first-line management option for uterine prolapse, especially amongst people who cannot or do not wish to undergo surgery, due to their affordability and low-risk profile compared to more invasive procedures.[6] When properly fitted, pessaries have been found to improve bulk and pressure symptoms associated with prolapse and improve quality of life measures.[3][5]

Surgical

[edit]There are many surgical options available for the treatment of uterine prolapse, which may be performed through a vaginal procedure or through the abdomen.[2][10] Generally, vaginal procedures are considered to be less invasive, offer a quicker recovery, and have a shorter operative time compared to abdominal procedures, but abdominal procedures offer longer-term results and potentially reduce risk of postoperative vaginal pain with intercourse.[2] Laparoscopic and robotic approaches to abdominal procedures in prolapse surgery have become more common as they require smaller incision sites, result in less blood loss, and have shorter hospital stays.[2][10]

Vaginal vault suspension (known as colpopexy), in which the upper portion of the vagina is surgically connected to another structure in the pelvis, is commonly performed in the treatment of uterine prolapse.[2][10] Forms of colpopexy include sacrocolpopexy, in which the vaginal vault is attached to the sacrum using a surgical mesh; sacrospinous ligament fixation, in which the upper vagina is attached to the sacrospinous ligaments; and uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension, in which the upper vagina is attached to the uterosacral ligaments.[2] Colpopexy can be performed with or without a hysterectomy. If performed without a hysterectomy, the procedure is known as a hysteropexy. Hysteropexy procedures include sacrohysteropexy and sacrospinous hysteropexy.[2]

In severe cases of prolapse where the person no longer desires vaginal intercourse and has contraindications to more invasive surgery, vaginal closure procedures may be offered.[10] These include LeFort partial colpocleisis and complete colpocleisis, in which the vagina is sutured closed.[10]

Also taken into consideration prior to surgery is use of native, or one's own, tissue versus a synthetic mesh. Generally, mesh may be considered in instances where the connective tissue is weak or absent, if there is an empty space at the surgical site that needs to be bridged, or if there is a high risk of prolapse recurrence.[2] Synthetic mesh is indicated and used for sacrocolpopexy and sacrohysteropexy procedures.[2] However, the use of synthetic mesh transvaginally, or within the vaginal tissue itself, is not indicated and is not routinely used for apical vaginal or uterine prolapse due to a lack of safety and effectiveness data, higher rate of mesh exposure compared with native tissue repair, and lack of data regarding long-term outcomes and complication rates.[3][2][10]

Outcomes

[edit]Overall, it appears that quality of life was found to be significantly improved for people with pelvic organ prolapse after surgical or pessary management.[5]

It can be difficult to determine success when discussing the outcomes of surgical intervention for pelvic organ prolapse due to multiple factors that can define success, such as anatomic success versus patient-reported outcome measures.[10] Improvement of vaginal bulge symptoms after surgery appears to be more of a measure of success for patients themselves than does anatomic success alone.[3]

The rate of pelvic organ prolapse recurrence following surgery depends on several factors, the most significant being patient age (patients younger than 60 years have higher likelihood of recurrence), POP-Q stage (POP-Q greater than 3 has higher likelihood of recurrence), surgeon's experience performing the procedure, and prior history of pelvic surgery.[11][12] Additionally, the type of surgery, for instance vaginal versus abdominal, also affects recurrence rate.[3][13] The rates of reoperation following pelvic organ prolapse surgery ranges from 3.4% to 9.7%.[3] Reoperation rates appear to be higher with transvaginal mesh repair compared to other procedures, due in part to complications such as mesh exposure.[3]

Epidemiology

[edit]Numerical values regarding prevalence of uterine prolapse differ based on whether the epidemiologic study in question uses a physical exam or a symptom questionnaire to determine the presence of prolapse.[3] Prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse was found to be consistently higher when physical exam was used (for uterine prolapse, this was 14.2%[14] in one study and 3.8% in another[3]) compared to a symptom-based determination in which the prevalence of any type of prolapse, including uterine prolapse, was 2.9% to 8% in the U.S.[3] Using Women's Health Initiative data, the incidence of grades 1 to 3 uterine prolapse was approximately 1.5/100 women-years and progression of uterine prolapse was found to be about 1.9%.[3]

History

[edit]The first mention of uterine prolapse in medical literature was in the Kahun papyrus, circa 1835 B.C.E, which read, "of a woman whose posterior, belly, and branching of her thighs are painful, say thou as to it, it is the falling of the womb."[15] The treatment at the time, documented on the Ebers papyrus, was to rub the afflicted person with a mixture of "oil of the earth [and] fedder",[15] or petroleum and manure.

Throughout Western history, advancements in the management of uterine prolapse have been hampered by a poor understanding of female pelvic anatomy.[15] During the Hippocratic era, approximately 460 B.C.E., it was thought that the uterus was akin to an animal.[15] Therefore, common treatments included fumigation, placing a foul-smelling object near the uterus to convince it to move into the vagina; the use of topical astringents, such as vinegar; and succussion, in which a woman was tied upside-down and shaken until the prolapse reduced.[15]

During the first century C.E., the Greek physician Soranus would disagree with many of these practices and recommended the use of wool, dipped in vinegar or wine and inserted into the vagina, to lift the uterus back into place.[15] He would also go on to recommend surgical removal of gangrenous portions of a prolapsed uterus.[15] However, these ideas did not become commonly accepted practices during that era, and the Middle Ages brought about a return to previous beliefs and practices for uterine prolapse.[15] In 1603, for instance, it was recommended that burning the prolapsed uterus with a hot iron would frighten it back into the vagina.[15]

Towards the end of the 16th century, pessaries became more common in the management of uterine prolapse, due in part to advances in anatomic knowledge of the female genitourinary tract earlier in the century.[15] Pessaries were usually made out of wax, metal, glass, or wood. Charles Goodyear's invention of volcanized rubber in the mid-1800s made it possible to produce pessaries that would not decompose.[15] However, even into the 1800s, alternative practices were still used, such as the use of sea-water douches, postural exercises, and leeching.[15]

Although the use of surgery in the treatment of uterine prolapse had been described previously, the 19th century saw advances in surgical techniques.[15] During the mid to late 1800s, surgical attempts to manage uterine prolapse included narrowing the vaginal vault, suturing the perineum, and amputating the cervix.[15] In 1877, LeFort described the process of a partial colpocleisis.[15] In 1861, Choppin in New Orleans reported the first instance in which vaginal hysterectomy was performed for uterine prolapse. Prior to that, vaginal hysterectomies were mainly performed for malignancies.[15]

Following Alwin Mackenrodt's 1895 publication of a comprehensive description of the female pelvic floor connective tissue, Fothergill began working on the Manchester-Fothergill surgery with the belief that the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments were key support structures for the uterus.[15] In 1907, Josef Haban and Julius Tandler theorized that the levator ani muscles were also very important for uterine support.[15] Combined with a better understanding of female pelvic floor connective tissue, these ideas would go on to influence surgical approaches for the treatment of uterine prolapse.[15]

By the early 20th century, different techniques for vaginal hysterectomies had been described and performed. As a result, post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse became more common and a growing concern for some surgeons, and new techniques to correct this complication were attempted.[15] In 1957, Arthure and Savage of London's Charing Cross Hospital, suspecting that uterine prolapse could not be cured with hysterectomy alone, published their surgical technique of sacral hysteropexy.[15] Their technique is still used in modern practice with the addition of a graft.[15]

Society and culture

[edit]Vaginal mesh kits were introduced to the U.S. market in 2004 through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pathway that did not require companies to demonstrate both safety and efficacy of the product if they were able to demonstrate that their product was similar to previous products already in the market.[3][18] However, there was concern over reports of increased rates of postoperative complications over the next several years. That, in addition to the lack of available data that transvaginal mesh products were superior to other forms of surgical intervention[18] and the expedited process which the vaginal mesh kits were introduced to the market, the FDA released a Safety Communication in 2011 that described serious complications associated with transvaginal mesh as "not rare".[3] In 2019, the FDA ordered manufacturers to halt sales transvaginal mesh intended for repair of pelvic organ prolapse.[3][19] This does not include surgical mesh used during sacrocolpopexy, sacrohysteropexy, or transurethral sling procedures.[19]

Since 2008, a number of class action lawsuits have been filed and settled against several manufacturers of transvaginal mesh after people reported complications following surgery.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ferri FF (28 May 2015). "Pelvic Organ Prolaps (Uterine Prolaspe)". Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2016 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-37822-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj Hoffman BL, Bradshaw KD, Schaffer JI, Halvorson LM, Corton MM (2020). Williams Gynecology (Fourth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-260-45687-5. OCLC 1120727710. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Barber MD, Bradley CS, Karram MM, Walters MD (2022). Walters and Karram urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 9780323697835. OCLC 1286723474.

- ^ a b c d e Kilpatrick CC. "Uterine and Apical Prolapse – Gynecology and Obstetrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Ghanbari Z, Ghaemi M, Shafiee A, Jelodarian P, Hosseini RS, Pouyamoghaddam S, Montazeri A (December 2022). "Quality of Life Following Pelvic Organ Prolapse Treatments in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 11 (23): 7166. doi:10.3390/jcm11237166. PMC 9738239. PMID 36498740.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hacker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ (2016). Hacker & Moore's Essentials of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-38852-8. OCLC 929903395.

- ^ a b Weintraub AY, Glinter H, Marcus-Braun N (2020). "Narrative review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse". International Braz J Urol. 46 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2018.0581. PMC 6968909. PMID 31851453.

- ^ Espiño-Albela A, Castaño-García C, Díaz-Mohedo E, Ibáñez-Vera AJ (May 2022). "Effects of Pelvic-Floor Muscle Training in Patients with Pelvic Organ Prolapse Approached with Surgery vs. Conservative Treatment: A Systematic Review". Journal of Personalized Medicine. 12 (5): 806. doi:10.3390/jpm12050806. PMC 9142907. PMID 35629228.

- ^ Dwyer L, Dowding D, Kearney R (July 2022). "What are the barriers and facilitators to self-management of chronic conditions reported by women? A systematic review". BMJ Open. 12 (7): e061655. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061655. PMC 9305798. PMID 35858726.

- ^ a b c d e f g de Tayrac R, Antosh DD, Baessler K, Cheon C, Deffieux X, Gutman R, et al. (October 2022). "Summary: 2021 International Consultation on Incontinence Evidence-Based Surgical Pathway for Pelvic Organ Prolapse". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 11 (20): 6106. doi:10.3390/jcm11206106. PMC 9605527. PMID 36294427.

- ^ Schulten SF, Claas-Quax MJ, Weemhoff M, van Eijndhoven HW, van Leijsen SA, Vergeldt TF, et al. (August 2022). "Risk factors for primary pelvic organ prolapse and prolapse recurrence: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 227 (2): 192–208. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.046. hdl:2066/282895. PMID 35500611. S2CID 248487990.

- ^ Shi W, Guo L (December 2023). "Risk factors for the recurrence of pelvic organ prolapse: a meta-analysis". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 43 (1): 2160929. doi:10.1080/01443615.2022.2160929. PMID 36645334. S2CID 255848480.

- ^ Maher C, Yeung E, Haya N, Christmann-Schmid C, Mowat A, Chen Z, Baessler K (July 2023). "Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (7): CD012376. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012376.pub2. PMC 10370901. PMID 37493538.

- ^ Rajan SS, Kohli N (6 March 2007). "Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in Primary Care: Epidemology and Risk Factors". In Culligan PJ, Goldber RP (eds.). Urogynecology in Primary Care. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-84628-167-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Downing KT (2012). "Uterine prolapse: from antiquity to today". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2012: 649459. doi:10.1155/2012/649459. PMC 3236436. PMID 22262975.

- ^ "De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. | Anatomia Collection: anatomical plates 1522-1867". anatomia.library.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "cách chữa sa tử cung". Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ a b Heneghan CJ, Goldacre B, Onakpoya I, Aronson JK, Jefferson T, Pluddemann A, Mahtani KR (December 2017). "Trials of transvaginal mesh devices for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic database review of the US FDA approval process". BMJ Open. 7 (12): e017125. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017125. PMC 5728256. PMID 29212782.

- ^ a b "Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh Implants". Center of Devices and Radiological Health. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 16 August 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Kaplan S, Goldstein M (16 April 2019). "F.D.A. Halts U.S. Sales of Pelvic Mesh, Citing Safety Concerns for Women". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

External links

[edit]- Illustrated description of Manchester Operation at atlasofpelvicsurgery.com

- Inverted uterus treatment, from Merck Professional