Prostatectomy

| Prostatectomy | |

|---|---|

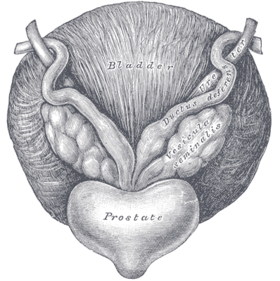

Anatomy of the prostate | |

| ICD-9-CM | 60.2-60.6 |

| MeSH | D011468 |

Prostatectomy (Greek, -prostates, "prostate", combined with the suffix -ektomē, "excision") is a medical term for the the surgical removal of all or part of the prostate gland. This operation is done for benign conditions that cause urinary retention, as well as for prostate cancer and other cancers of the pelvis.

There are two main types of prostatectomies. A simple prostatectomy (also known as a subtotal prostatectomy) is when only part of the prostate is removed. Simple prostatectomies are typically only done for benign conditions.[1] A radical prostatectomy, the removal of the entire prostate gland, the seminal vesicles and the vas deferens, is performed for malignant cancer.[2]

There are multiple ways the operation can be done: as an open surgery (with a large incision through the lower abdomen), laparoscopically with the help of a robot (a type of minimally invasive surgery), through the urethra or through the perineum.

Other terms that can be used to describe a prostatectomy, include

- Nerve-sparing: the blood vessels and nerves that promote penile erections are left behind in the body and not taken out with the prostate

- Limited pelvic lymph node dissection: the lymph nodes surrounding and close to the prostate are taken out (typically the area defined by external iliac vein anteriorly, the obturator nerve posteriorly, the origin of the internal iliac artery proximally, Cooper's ligament distally, the bladder medially and the pelvic side wall laterally[3]).

- Extended pelvic lymph node dissection: lymph nodes farther away from the prostate are taken out also (typically the area defined in a limited PLND with the posterior boundary as the floor of the pelvis[3]).

Medical uses

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Contra-indications

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Techniques and approaches

There are several forms of the operation:

Transurethral resection of the prostate

This is used for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and sometimes for symptomatic relief in prostate cancer. A cystoscope [a resectoscope which has a 30 degree viewing angle, along with resectoscopy sheath & working element] is passed up the urethra to the prostate, where the surrounding prostate tissue is excised. This is a common operation for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and outcomes are excellent for a high percentage of these patients (80-90%).

Conventional (monopolar) TURP

The conventional TURP method in tissue removal utilizes a wire loop with electrical current flowing in one direction (thus monopolar) through the resectoscope to cut the tissue. A grounding ESU pad and irrigation by a nonconducting fluid is required to prevent this current from disturbing surrounding tissues. This fluid (usually glycine) can cause damage to surrounding tissue after prolonged exposure, resulting in TUR syndrome, so surgery time is limited.

Bipolar TURP

Bipolar TURP is a newer technique that uses bipolar current to remove the tissue.[4] [5] Bipolar TURP allows saline irrigation and eliminates the need for an ESU grounding pad thus preventing post-TURP hyponatremia (TUR syndrome) and reducing other complications. As a result bipolar Turp is also not subject to the same surgical time constraints of conventional TURP.

Laser prostate surgery

Another surgical method utilizes laser energy to remove tissue. With laser prostate surgery a fiber optic cable pushed through the urethra is used to transmit lasers such as holmium-Nd:YAG high powered "red" or potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) "green" to vaporize the adenoma. More recently the KTP laser has been supplanted by a higher power laser source based on a lithium triborate crystal, though it is still commonly referred to as a "Greenlight" or KTP procedure. The specific advantages of utilizing laser energy rather than a traditional electrosurgical TURP is a decrease in the relative blood loss, elimination of the risk of post-TURP hyponatremia (TUR syndrome), the ability to treat larger glands, as well as treating patients who are actively being treated with anti-coagulation therapy for unrelated diagnoses.

Plasmakinetic resection

This procedure uses ionized vapour that heats up by low voltage electricity and semi-spherical button to vaporize the prostate tissue from inside and only leave a 2–3 mm shell. This procedure is considered to be the least intrusive of all techniques currently available and has less post-operative complications and a short convalescence.[6]

Open prostatectomy

In an open prostatectomy the prostate is accessed through an incision that allows manual manipulation and open visualization through the incision. The most common types of open prostatectomy are radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) and radical perineal prostatectomy (RPP).

Radical retropubic prostatectomy

With RRP, an incision is made in the lower abdomen, and the prostate is removed, by going behind the pubic bone (retropubic).

Radical perineal prostatectomy

In RPP an incision is made in the perineum, midway between the rectum and scrotum through which the prostate is removed. This procedure has become less common due to limited access to lymph nodes and difficulty in avoiding nerves.

Suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy

Another type of open prostatectomy is suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy (SPP), or the Hryntschak Procedure, which was pioneered in the early 1930s by the Austrian Urologist, Theodor Hryntschak (1889 – 1952), where in an incision is made in the bladder. SPP remains a common surgical treatment for BPH in Africa but has largely been supplanted by TURP in the West for this application.[7] SPP may be indicated for use with large patients and prostates because of the surgical time constraints associated with conventional TURP.

Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy procedure

This is a laparoscopic procedure involving four small incisions made in the abdomen used to remove the entire prostate for treatment of prostate cancer.

Computer-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (CALP)

Computer-assisted instruments are inserted through several small abdominal incisions and controlled by a surgeon. Some use the term 'robotic' for short, in place of the term 'computer-assisted'. However, procedures performed with a computer-assisted device are performed by a surgeon, not a robot. The computer-assisted device gives the surgeon more dexterity and better vision, but no tactile feedback compared to conventional laparoscopy. When performed by a surgeon who is specifically trained and well experienced in CALP, there can be similar advantages over open prostatectomy, including smaller incisions, less pain, less bleeding, less risk of infection, faster healing time, and shorter hospital stay.[8] The cost of this procedure is higher, whereas long-term functional and oncological superiority has yet to be established.[9][10][11]

Risks and complications

Sexual effects

Surgical removal of the prostate risks an increased likelihood that patients will experience erectile dysfunction. Nerve-sparing surgery reduces the risk that patients will experience erectile dysfunction. However, the experience and the skill of the nerve-sparing surgeon, as well as any surgeon are critical determinants of the likelihood of positive erectile function of the patient.[12]

Remedies to post-operative sexual dysfunction

Very few surgeons will claim that patients return to the erectile experience they had prior to surgery. The rates of erectile recovery that surgeons often cite are qualified by the addition of Viagra to the recovery regimen.[13]

Remedies to the problem of post-operative sexual dysfunction include:[14]

- Medications

- Intraurethral suppositories

- Penile injections

- Vacuum devices

- Penile implants

Recovery

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Epidemiology

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

History

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Costs

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

References

- ^ Khera, MD, MBA, MPH, Mohit (October 23, 2013). "Simple Prostatectomy". Medscape. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McAninch, Jack W.; Lue (2008). Smith and Tanagho's General Urology. New York: McGraw Hill Medical. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-07-162497-8.

- ^ a b Wider, Jeff A. (2014). Pocket Guide to Urology. USA. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-9672845-6-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Starkman JS, Santucci RA (2005). "Comparison of bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate with standard transurethral prostatectomy: shorter stay, earlier catheter removal and fewer complications". BJU Int. 95 (1): 69–71. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05253.x. PMID 15638897.

- ^ "Bipolar versus Monopolar TURP: A Prospective Controlled Study at two Urology Centers". 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ http://www.nature.com/pcan/journal/v10/n1/abs/4500907a.html

- ^ Nthumba, P.M.; Bird, P.A. (November–December 2006). "Suprapubic Prostatectomy with and without Continuous Bladder Irrigation in a Community with Limited Resources". East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 12 (2): 53–58. ISSN 1024-297X. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Center for the Advancement of Health; August 29, 2005; Robot-assisted Prostate Surgery Has Possible Benefits, High Cost [1]

- ^ Cost Analysis of Radical Retropubic, Perineal, and Robotic Prostatectomy; Scott V. Burgess, Fatih Atug, Erik P. Castle, Rodney Davis, Raju Thomas; Journal of Endourology 2006 20:10, 827-830 [2]

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2009.11.008, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.eururo.2009.11.008instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.017, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.017instead. - ^ John P. Mulhall, M.D., Saving Your Sex Life: A Guide for Men with Prostate Cancer, Chicago, Hilton Publishing Company, 2008, p. 56, 58, Table 1: Factors Predicting Erectile Function Recovery after Radical Prostatectomy, p. 65.

- ^ John P. Mulhall, M.D., Saving Your Sex Life: A Guide for Men with Prostate Cancer, Chicago, Hilton Publishing Company, 2008, p. 69.

- ^ John P. Mulhall, M.D., Saving Your Sex Life: A Guide for Men with Prostate Cancer, Chicago, Hilton Publishing Company, 2008