Prostatectomy

| Prostatectomy | |

|---|---|

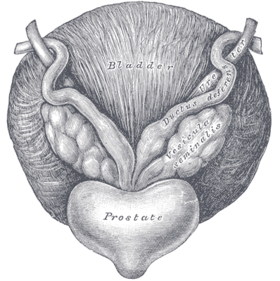

Anatomy of the prostate | |

| ICD-9-CM | 60.2-60.6 |

| MeSH | D011468 |

Prostatectomy (Greek, -prostates, "prostate", combined with the suffix -ektomē, "excision") is a medical term for the surgical removal of all or part of the prostate gland. This operation is done for benign conditions that cause urinary retention, as well as for prostate cancer and other cancers of the pelvis.

There are two main types of prostatectomies. A simple prostatectomy (also known as a subtotal prostatectomy) is when only part of the prostate is removed. Simple prostatectomies are typically only done for benign conditions.[1] A radical prostatectomy, the removal of the entire prostate gland, the seminal vesicles and the vas deferens, is performed for malignant cancer.[2]

There are multiple ways the operation can be done: as an open surgery (with a large incision through the lower abdomen), laparoscopically with the help of a robot (a type of minimally invasive surgery), through the urethra or through the perineum.

Other terms that can be used to describe a prostatectomy, include

- Nerve-sparing: the blood vessels and nerves that promote penile erections are left behind in the body and not taken out with the prostate

- Limited pelvic lymph node dissection: the lymph nodes surrounding and close to the prostate are taken out (typically the area defined by external iliac vein anteriorly, the obturator nerve posteriorly, the origin of the internal iliac artery proximally, Cooper's ligament distally, the bladder medially and the pelvic side wall laterally[3]).

- Extended pelvic lymph node dissection: lymph nodes farther away from the prostate are taken out also (typically the area defined in a limited PLND with the posterior boundary as the floor of the pelvis[3]).

Medical uses

Benign

Indications for removal of the prostate in a benign setting include acute urinary retention, persistent of recurrent urinary tract infections, uncontrollable hematuria, bladder stones secondary to bladder outlet obstruction, significant symptoms from bladder outlet obstruction that are refractory to medical or minimally invasive therapy, and renal insufficiency secondary to chronic bladder outlet obstruction.[4]

Malignant

A radical prostatectomy is done in the setting of a malignancy i.e. cancer. For prostate cancer, the best treatment often depends on the risk level of the cancer. For most prostate cancers classified as 'very low risk' and 'low risk,' radical prostatectomy is one of several treatment options (including radiation and active surveillance). For intermediate and high risk prostate cancers, radical prostatectomy is often recommended in addition to other treatment options. Radical prostatectomy is not recommended in the setting of known metastases, when the cancer is known to have spread through the prostate to the lymph nodes or other parts of the body.[5] Prior to decision making about the best treatment option for higher risk cancers, imaging using CT, MRI or bone scans are done to make sure the cancer has not spread outside of the prostate.

Contra-indications

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Techniques and approaches

There are several ways a prostatectomy can be done:

Open

In an open prostatectomy, the prostate is accessed through a large single incision through either the lower abdomen or the perineum. Further descriptive terms describe how the prostate is accessed anatomically through this incision (retropubic vs. suprapubic vs. perineal). A retropubic prostatectomy describes a procedure that accesses the prostate by going through the lower abdomen and behind the pubic bone. A suprapubic prostatectomy describes a procedure cuts through the lower abdomen and through the bladder to access the prostate. A perineal prostatectomy is done by making an incision between the rectum and scrotum on the underside of the abdomen.

Transurethral

Another way to take out the prostate is through the urethral opening at the tip of the penis. This is referred to as a TURP, or transurethral resection of the prostate. This approach is usually used for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and sometimes for symptomatic relief in prostate cancer. A cystoscope [a resectoscope which has a 30-degree viewing angle, along with resectoscopy sheath & working element] is passed up the urethra to the prostate, where the surrounding prostate tissue is excised.

A TURP using a monopolar device utilizes a wire loop with electric current flowing in one direction (thus monopolar) through the resectoscope to cut the tissue. A grounding ESU pad and irrigation by a nonconducting fluid is required to prevent this current from disturbing surrounding tissues. This fluid (usually glycine) can cause damage to surrounding tissue after prolonged exposure, resulting in TUR syndrome, so surgery time is limited.

TURP using a bipolar device is a newer technique that uses bipolar current to remove the tissue.[6] [7] Bipolar TURP allows saline irrigation and eliminates the need for an ESU grounding pad thus preventing post-TURP hyponatremia (TUR syndrome) and reducing other complications. As a result, bipolar TURP is also not subject to the same surgical time constraints of conventional TURP.

Another transurethral method utilizes laser energy to remove tissue. With laser prostate surgery a fiber optic cable pushed through the urethra is used to transmit lasers such as holmium-Nd:YAG high powered "red" or potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) "green" to vaporize the adenoma. More recently the KTP laser has been supplanted by a higher power laser source based on a lithium triborate crystal, though it is still commonly referred to as a "Greenlight" or KTP procedure. The specific advantages of utilizing laser energy rather than a traditional electrosurgical TURP is a decrease in the relative blood loss, elimination of the risk of post-TURP hyponatremia (TUR syndrome), the ability to treat larger glands, as well as treating patients who are actively being treated with anti-coagulation therapy for unrelated diagnoses.

Minimally invasive

Robotic-assisted instruments are inserted through several small abdominal incisions and controlled by a surgeon. Some use the term 'robotic' for short, in place of the term 'computer-assisted'. However, procedures performed with a computer-assisted device are performed by a surgeon, not a robot. The computer-assisted device gives the surgeon more dexterity and better vision, but no tactile feedback compared to conventional laparoscopy. When performed by a surgeon who is specifically trained and well experienced in CALP, there can be similar advantages over open prostatectomy, including smaller incisions, less pain, less bleeding, less risk of infection, faster healing time, and shorter hospital stay.[8] The cost of this procedure is higher, whereas long-term functional and oncological superiority has yet to be established.[9][10][11]

Risks and complications

Any surgical procedure has risks associated with it. Complications that occur in the period right after any surgical procedure, including a prostatectomy, include a risk of bleeding, a risk of infection at the site of incision or throughout the whole body, a risk of a blood clot occurring in the leg or lung, a risk of a heart attack or stroke, and a risk of death.

Severe irritation takes place if a latex catheter is inserted in the urinary tract of a person allergic to latex. That is especially severe in case of a radical prostatectomy due to the open wound there and the exposure lasting e.g. two weeks. Intense pain may indicate such situation.[12]

A 2005 article in the medical journal Reviews in Urology listed the incidence of several complications following radical prostatectomy: mortality <0.3%, impotence >50%, ejaculatory dysfunction 100%, orgasmic dysfunction 50%, incontinence <5%-30%, pulmonary embolism <1%, rectal injury <1%, urethral stricture <5%, and transfusion 20%.[13] Long term complications that are common and specific to a prostatectomy include the following:

Erectile dysfunction

Surgical removal of the prostate contains an increased likelihood that patients will experience erectile dysfunction. Nerve-sparing surgery reduces the risk that patients will experience erectile dysfunction. However, the experience and the skill of the nerve-sparing surgeon, as well as any surgeon are critical determinants of the likelihood of positive erectile function of the patient.[14]

Following a prostatectomy, patients will not be able to ejaculate semen due to the nature of the procedure, resulting permanent necessity of assisted reproductive techniques in case of desires of future fertility.[15] Preservation of normal ejaculation is possible after TUR-Prostatectomy, open or laser enucleation of adenoma and laser vaporisation of prostate. However, retrograde ejaculation is a common problem. Recently ejaculation preservation is aimed by new techniques.[16]

Urinary incontinence

Patients who undergo a prostatectomy have an increased risk of leaking small amount of urine immediately after surgery and for the long-term leading to needing a urine incontinence device, like a condom catheter. A large analysis of the incidence of urinary incontinence found that at 12 months after surgery, an average of 75% of patients needed no pad, while 9%-16% of patients needed a safety pad, Things associated with an increased risk of urinary incontinence at 12 months after surgery include higher age, higher BMI, more comorbidities, and larger prostates, as well as experience and technique of the surgeon.[17]

Remedies to post-operative sexual dysfunction

Very few surgeons will claim that patients return to the erectile experience they had prior to surgery. The rates of erectile recovery that surgeons often cite are qualified by the addition of Viagra to the recovery regimen.[18]

Remedies to the problem of post-operative sexual dysfunction include:[19]

- Medications

- Intraurethral suppositories

- Penile injections

- Vacuum devices

- Penile implants

Recovery

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Epidemiology

The use of radical prostatectomy as treatment for prostate cancer increased significantly from 1980 to 1990.[20] As of 2000, the median age of men undergoing radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer is 62.[20]

Though this is a very common procedure, the experience level of the surgeon doing the operation is very important on the outcomes and rate of complications and side effects. The more number of prostatectomies the surgeon has done improves the outcomes of the patient. This is true for prostatectomies done as open procedures[21] and those done using minimally invasive techniques.[22]

History

William Belfield, MD is generally credited for performing the first intentional prostatectomy via the suprapubic route in 1885, 1886 or 1887 at Cook County Hospital in Chicago.[23][24] Hugh H. Young, MD in collaboration with William Stewart Halsted, MD developed the open, radical, perineal prostatectomy in 1904 at Johns Hopkins Brady Urological Institute, the first version of the procedure that became generally feasible.[25] The Irish surgeon Terence Millin, MD (1903–1980) developed the radical retropubic prostatectomy in 1945.[26] American urologist Patrick C. Walsh, MD (1938—present) developed the modern nerve-sparing, retropubic prostatectomy with minimal blood loss.[27] The first laparoscopic prostatectomy was performed in 1991 by William Schuessler, MD and colleagues in Texas.[28]

Costs

A 2014 survey of prostatectomy fees for uninsured patients at 70 United States Hospitals found an average facility fee of $34,720 and average surgeon and anesthesiologist fees of $8,280.[29]

See also

References

- ^ Khera, MD, MBA, MPH, Mohit (October 23, 2013). "Simple Prostatectomy". Medscape. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McAninch, Jack W.; Lue (2008). Smith and Tanagho's General Urology. New York: McGraw Hill Medical. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-07-162497-8.

- ^ a b Wider, Jeff A. (2014). Pocket Guide to Urology. USA. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-9672845-6-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Khera, Mohit (October 23, 2013). "Simple Prostatectomy". Medscape. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ "NCCN Guidelines version 1.2015 - Prostate Cancer" (PDF). NCCN Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. October 24, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ Starkman JS, Santucci RA (2005). "Comparison of bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate with standard transurethral prostatectomy: shorter stay, earlier catheter removal and fewer complications". BJU Int. 95 (1): 69–71. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05253.x. PMID 15638897.

- ^ "Bipolar versus Monopolar TURP: A Prospective Controlled Study at two Urology Centers". 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Center for the Advancement of Health; August 29, 2005; Robot-assisted Prostate Surgery Has Possible Benefits, High Cost [1]

- ^ Cost Analysis of Radical Retropubic, Perineal, and Robotic Prostatectomy; Scott V. Burgess, Fatih Atug, Erik P. Castle, Rodney Davis, Raju Thomas; Journal of Endourology 2006 20:10, 827–830 [2]

- ^ Bolenz, C.; Gupta, A.; Hotze, T.; Ho, R.; Cadeddu, J.; Roehrborn, C.; Lotan, Y. (2010). "Cost comparison of robotic, laparoscopic, and open radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer". European Urology. 57 (3): 453–458. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2009.11.008. PMID 19931979.

- ^ Barocas, D. A.; Salem, S.; Kordan, Y.; Herrell, S. D.; Chang, S. S.; Clark, P. E.; Davis, R.; Baumgartner, R.; Phillips, S.; Cookson, M. S.; Smith Jr, J. A. (2010). "Robotic Assisted Laparoscopic Prostatectomy Versus Radical Retropubic Prostatectomy for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: Comparison of Short-Term Biochemical Recurrence-Free Survival". The Journal of Urology. 183 (3): 990–996. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.017. PMID 20083261.

- ^ http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/test_procedures/urology/radical_prostatectomy_92,p09111/

- ^ Sexual Dysfunction after Radical Prostatectomy; Andrew R McCullough; Reviews in Urology; 2005 7:(Suppl 2), S3–S10.

- ^ John P. Mulhall, M.D., Saving Your Sex Life: A Guide for Men with Prostate Cancer, Chicago, Hilton Publishing Company, 2008, pp. 56, 58, Table 1: Factors Predicting Erectile Function Recovery after Radical Prostatectomy, p. 65.

- ^ Tran, Stéphanie; Boissier, Romain; Perrin, Jeanne; Karsenty, Gilles; Lechevallier, Eric. "Review of the Different Treatments and Management for Prostate Cancer and Fertility". Urology. 86 (5): 936–941. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2015.07.010.

- ^ Alloussi, Saladin Helmut; Lang, Christoph; Eichel, Robert; Alloussi, Schahnaz (2013-08-19). "Ejaculation-Preserving Transurethral Resection of Prostate and Bladder Neck: Short- and Long-Term Results of a New Innovative Resection Technique". Journal of Endourology. 28 (1): 84–89. doi:10.1089/end.2013.0093. ISSN 0892-7790.

- ^ Ficarra, Vincenzo; Novara, Giacomo; Rosen, Raymond C.; Artibani, Walter; Carroll, Peter R.; Costello, Anthony; Menon, Mani; Montorsi, Francesco; Patel, Vipul R. (September 2012). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy". European Urology. 62 (3): 405–417. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.045. ISSN 1873-7560. PMID 22749852.

- ^ John P. Mulhall, M.D., Saving Your Sex Life: A Guide for Men with Prostate Cancer, Chicago, Hilton Publishing Company, 2008, p. 69.

- ^ John P. Mulhall, M.D., Saving Your Sex Life: A Guide for Men with Prostate Cancer, Chicago, Hilton Publishing Company, 2008

- ^ a b Moul, J. W. (August 2002). "Epidemiology of radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer in the era of prostate-specific antigen: an overview of the Department of Defense Center for Prostate Disease Research national database". Surgery. 132: 213–9. doi:10.1067/msy.2002.125315. PMID 12219014.

- ^ Vickers, A., Bianco, F., Cronin, A., Eastham, J., Klein, E., Kattan, M., Scardino, P. (April 2010). "The learning curve for surgical margins after open radical prostatectomy: implications for margin status as an oncological end point". Journal of Urology. 183: 1360–5. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.015. PMID 20171687.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vickers, A. J., Savage C. J, Hruza, M., Tuerk, I., Koenig, P., Martínez-Piñeiro, L., Janetschek, G., Guillonneau, B. (May 2009). "The surgical learning curve for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a retrospective cohort study". Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):475. 10: 475–80. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70079-8. PMID 19342300.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thorndike, P (1903). "Present status of the surgery of prostate gland". Boston Med Surg J. 149 (7): 167.

- ^ Zorgniotti, AW (2012). "Suprapubic prostatectomy: An Anglo-American success story". In Hinman, Jr, F; Boyarsky, S (eds.). Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy. Spring. pp. 45–58. ISBN 978-1-4612-5478-2.

- ^ Young, HH (1905). "VIII. Conservative perineal prostatectomy: The results of two years' experience and report of seventy-five cases". Ann Surg. 41 (4): 549–557.

- ^ Millin, T (1945). "Retropubic prostatectomy: A new extravesical technique report; report of 20 cases". Lancet. 2 (6380): 693–696.

- ^ Walsh, PC (2007). "The discovery of the cavernous nerves and development of nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy". J Urol. 177 (5): 1632–1635.

- ^ Schuessler, WW; Schulam, PG; Clayman, RV; Kavoussi, LR (1997). "Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: Initial short-term experience". Urology. 50 (6): 854–857.

- ^ Pate, S. C., Uhlman, M. A., Rosenthal, J. A., Cram, P., Erickson, B. A. (March 2014). "Variations in the open market costs for prostate cancer surgery: a survey of US hospitals". Urology. 83 (3): 626–30. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2013.09.066. PMID 24439795.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)