Pure (Miller novel)

First edition | |

| Author | Andrew Miller |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Royston Knipe |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical novel |

| Set in | Paris, 1786 |

| Publisher | Sceptre |

Publication date | 9 June 2011 |

| Publication place | England |

| Media type | Print and audiobook |

| Pages | 346 |

| ISBN | 978-1-4447-2425-7 |

| OCLC | 729332720 |

| 823.92 | |

| LC Class | PR6063 .I3564 |

| Preceded by | One Morning Like a Bird (2008) |

Pure is a 2011 novel by English author Andrew Miller. The book is the sixth novel by Miller and was released on 9 June 2011 in the United Kingdom through Sceptre, an imprint of Hodder & Stoughton. The novel is set in pre-revolutionary France and the upcoming turmoil is a consistent theme throughout. It follows an engineer named Jean-Baptiste Baratte and chronicles his efforts in clearing an overfilled graveyard that is polluting the surrounding area. Baratte makes friends and enemies as the cemetery is both loved and hated by the people of the district.

Miller was inspired to write about the Les Innocents Cemetery after reading historian Philippe Ariès's brief description of its clearing and imagining the theatrics that must have been involved. The novel received positive reviews, particularly noting the quality of the writing. The novel was awarded the Costa Book Award 2011 for "Best Novel" and "Book of the Year", and was nominated for the Walter Scott Prize and South Bank award.

Plot

[edit]A 28-year-old engineer named Jean-Baptiste Baratte is tasked with the removal of the Les Innocents cemetery from Les Halles, Paris in 1786 (the Place Joachim-du-Bellay now occupies the area) and the removal of its church. Baratte is an engineer with a single decorative bridge, built in his small hometown, comprising his entire career, and, as such, is somewhat surprised by his appointment; he does, however, endeavour to complete his task.

The cemetery has been in use for many years but, given the number of people buried in such a small area, the bodies have begun to overflow and fall into the neighbouring houses as greater excavations take place and basement walls are weakened. The entire area is also permeated with a foul smell, turning fresh produce rotten in far shorter times than natural and tainting the breath of those who live there.

While scouting the cemetery before his work begins Baratte goes to stay with the Monnards, a middle-class family with a beautiful young daughter, Ziguette. In the cemetery Baratte makes the acquaintance of Armand, the church organist who continues to play, but for no one as the church has long since closed, the reclusive Père Colbert, the mad church priest, and 14-year-old Jeanne, the granddaughter of the sexton, who has grown up in the cemetery and is instrumental to Baratte's research.

Baratte initially keeps his work secret from his acquaintances but they eventually come to know of his work and most accept it reluctantly though Ziguette, in particular, seems upset about the destruction of the cemetery.

For the work, Baratte hires men from a mine that he formerly worked in and also hires his former friend, Lacoeur to come as a foreman. The work goes well until suddenly one-night Baratte is attacked by Ziguette who wounds him in his head. Ziguette is sent away and Baratte is left with permanent injuries including severe migraines, difficulty reading, and the loss of a sense of taste. After the injury, Baratte decides to move Heloïse, a known prostitute in the area, into the Monnard's home as his companion.

Though all goes well for Baratte after the injury he is called to the cemetery one night where he learns that Jeanne was attacked and raped by Lacoeur who commits suicide in penance. Baratte is ordered to cover up the suicide by his superiors and a rumour develops that he killed Lacoeur defending Heloïse.

Characters

[edit]- Jean-Baptiste Baratte – the protagonist of the novel; engineering graduate of the École des Ponts et Chaussées and overseer of the project; originally from Normandy. The name is a reference to the biblical John the Baptist.[1][2] Barattes nickname is "Bêche", which is French for "Spade", a reference to his career.[3]

- Armand – the church's flamboyant and alcoholic organist; and close friend to Baratte; with links to "the party of the future".

- Héloïse Goddard – a prostitute, also known as "The Austrian" because of her resemblance to Queen Marie Antoinette, who specialises in indulging the peculiar perversions of her clients; also Baratte's love interest.

- Lecoeur – Baratte's old friend brought in as the foreman to the miners undertaking the excavation. English translation of the name is "The Heart".[4]

- Ziguette Monnard – Barrate's landlord's daughter who attacks Baratte in the middle of the night, in opposition to his work.

- Marie – maid to the Monnards who spies on Baratte sleeping during the night.

- Jeanne – 14-year-old granddaughter to the church's sexton.

- Dr.Guillotin – a doctor who is observing the progress of the excavation for research purposes.

- Père Colbert – the church's mad priest.

Themes

[edit]

The novel takes place immediately before the French Revolution and, while not discussed in the novel, a number of sights and incidents foreshadow the impending events. Clare Clark, in The Guardian, stated "as Baratte's story unfolds, the impending revolution hangs over the narrative like the blade of the guillotine to come", identifying a number of auguries of the future turmoil; including "an organist play[ing] to an empty church", the local theatre putting on a production of Beaumarchais' The Marriage of Figaro; and a cart displaying the phrase "M Hulot et Fils: Déménageurs à la Noblesse" on its side (English: M Hulot and Son: Movers to the Nobility).[2] In The Week, Michael Bywater stated he felt that the novel has "a sense in the air that something decisive is going to happen, and happen soon".[1]

Thomas Quinn for The Big Issue opined that the removal of the cemetery as a whole could be construed as Miller asking "whether we should sweep away the past in the name of progress" or if we should be "confronting set ideas about what makes us human in the first place".[5]

Miller also aimed to imbue the novel with a sense of anxiety, especially concerning the decisions Jean-Baptiste must take. Commenting on fiction in general in an interview with Lorna Bradbury for The Daily Telegraph, Miller stated that "a novel is a collection of anxieties held together, more or less well, more or less interestingly, by the chicken wire of plot".[6] Bradbury goes on to state "that is absolutely the case with Pure, which details multiple counts of insanity as the panic-inducing business of razing the cemetery takes hold".[6] Of Pure specifically, Miller stated that "I'm interested in what anxiety does to people", "in what happens when they can't respond the way the world expects them to. What happens when our sense of ourselves falls away under the pressure of circumstances? What's left? That's a very interesting place to be."[6]

Another theme prevalent in the novel is death, influenced in part by the death of Miller's father, to whom the book is dedicated. Miller stated that "after the age of fortysomething, death is a taste in your mouth, and never goes away again".[7] The reviewer for The Australian called the novel "a meditation on death and the frailty of the body and spirit".[8]

Development

[edit]Miller first heard about the clearing of the Les Innocents cemetery ten years before writing the novel, when reading a book by French medievalist and historian, Philippe Ariès; specifically, his 1977 work entitled L'Homme devant la mort, or The Hour of Our Death. Ariès' book did not go into a great deal of detail concerning this actual event, however, Miller was "taken by the theatricality" of it and decided to write a novel based around the exhumation.[9] In an interview with Kira Cochrane he stated the novel "appealed to [him] as being interesting, visually interesting", stating "it was when it all happened that made it stand out. It's the 1780s, a few years before the French revolution".[9] Miller further stated that his father's occupation as a doctor also had some bearing on his interest in the human body, stating "I grew up looking at these things – my Beano and Dandy were the BMJ and The Lancet".[9] Miller decided not to include any French dialogue in the novel as "it is so pretentious" in an English-language novel, stating "I was afraid that my editor would strike it out".[10]

Publication history

[edit]- 2011, UK, Sceptre ISBN 978-1-4447-2425-7, pub date 9 Jun 2011, Hardback

- 2012, UK, Sceptre ISBN 978-1-4447-2428-8, pub date 5 Jan 2012, Paperback

- 2012, UK, Dreamscape Media, pub date 29 May 2012, Audiobook

- 2012, USA, Europa Editions ISBN 978-1-60945-067-0, pub date 29 May 2012, Paperback

Novel's title

[edit]The novel's title can be attributed to a number of aspects of the work. The purification of the cemetery and the recent change in social mores (in relation to dirt and decay) being the most immediately apparent.[7] James Kidd, writing for The Independent, stated "if this suggests one definition of purity, others are suggested by political undercurrents. Namely, the ideals that helped shape the French Revolution: Voltaire's call to reason, Rousseau's call to equality, and Robespierre's call to arms."[7]

Cover

[edit]

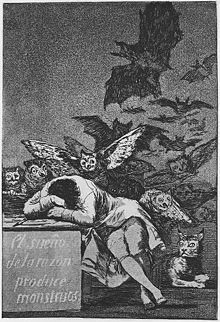

The cover, created by Royston Knipe, was based on Francisco Goya's etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. It features Baratte in his pistachio green silk Charvet suit replacing the recumbent Goya in his self-portrait. Instead of the owls and bats which assail Goya in The Sleep of Reason, Knipe used ravens.[11] The cover was noted by The Guardian writer John Dugdale, in an article about the marketing aspect of book cover design, as being unique in the current market. He stated that; along with the covers for The Sense of an Ending and The Tiger's Wife; "None of the three looks like anything else in bookshops".[12]

Audio adaptations

[edit]A Sweet Talk production of Pure was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 as part of the Book at Bedtime programme from 20–31 August 2012; it was read by John Sessions, abridged by Jeremy Osborne and produced by Rosalynd Ward.[13][14]

The novel was also the inspiration for two songs written by Bath based musicians, The Bookshop Band, namely "The downfall of Les Innocents" and "The Engineer's Paris" from their album Into The Farthest Reaches.[15]

Reception

[edit]Amid all this gloom glows the writing, like a new penny in the dirt. Miller's newly minted sentences – from the doctor's darkly comic quips to descriptions of eyes as "two black nails hammered into a skull", or coffins opened "like oysters" – are arresting, often unsettling and always thought provoking.

The novel received almost universal praise, with reviewers praising Miller's approach to the subject, his vividly rendered characters and setting and his eloquent prose.

In a review for The Independent, James Urquhart found the novel to be "richly textured" and that it had "energetic, acutely observed characters"; stating "Miller populates Baratte's quest for equanimity with these lush and tart characters, seductively fleshed out, who collectively help to deliver the bittersweet resolution of Baratte's professional and personal travails."[16] Clare Clark, writing for The Guardian, found that "Miller is a writer of subtlety and skill" and stated that she found the novel to be much like a parable, stating that "Unlike many parables, however, Pure is neither laboured nor leaden. Miller writes like a poet, with a deceptive simplicity – his sentences and images are intense distillations, conjuring the fleeting details of existence with clarity." Clark goes on to say that "Pure defies the ordinary conventions of storytelling, slipping dream-like between lucidity and a kind of abstracted elusiveness. The characters are often opaque. The narrative lacks dramatic structure, unfolding in the present tense much as life does, without clear shape or climax" and found that "The result is a book that is unsettling and, ultimately, optimistic."[2] The Australian's Jennifer Levasseur found Pure to be "Well-executed and inventive", stating that she found the plot "Historically convincing, immediately engaging and intellectually stimulating". She went on to state, of Miller himself: "Miller is the calibre of writer who deserves to be followed regardless of topic, time period or setting because of his astonishing dexterity with language, his piercing observations and his ability to combine rollicking storytelling with depth of character."[8]

Novelist Brian Lynch, writing for the Irish Independent found "The story in Pure is simple, almost dreamlike, a realistic fantasy, a violent fairy tale for adults", stating "At its best Pure shimmers".[17] The novel received two reviews from The Daily Telegraph. Freya Johnston found that "Miller lingers up close on details: sour breath, decaying objects, pretty clothes, flames, smells, eyelashes. He is a close observer of cats" and stated, of Baratte's project as a whole, "Miller intimately imagines how it might have felt to witness it."[18] Holly Kyte found Pure to be "irresistibly compelling" and "Exquisite inside and out". She stated that "Every so often a historical novel comes along that is so natural, so far from pastiche, so modern, that it thrills and expands the mind" and that she found that "Pure is a near-faultless thing: detailed, symbolic and richly evocative of a time, place and man in dangerous flux. It is brilliance distilled, with very few impurities."[11] Suzi Feay, for the Financial Times, stated "Quietly powerful, consistently surprising, Pure is a fine addition to a substantial body of work" and also noted that "Miller's portraits of women and the poor are thoughtful and subtle."[19] Writing for the Daily Express Vanessa Berridge found the novel to be "very atmospheric, if not to say positively creepy at times" and stated that "Miller's eloquent novel overflows with vitality and colour. It is packed with personal and physical details that evoke 18th-century Paris with startling immediacy."[20]

Above all, pre-revolutionary Paris is evoked in pungent detail, from its fragrant bread and reeking piss-pots to the texture of clothing, the grimness of medical procedure and the myriad colours of excavated bone. By concentrating on the bit players and byways of history, Miller conjures up an eerily tangible vanished world.

In a review for The Observer, Leo Robson found the novel to be somewhat underwhelming, stating that "It is disappointing, given the vitality of the novel's setting and set-up, that Miller fails to achieve corresponding dynamism in the development of plot and character", adding that "as a prose writer, Miller appears averse to taking risks, which means no pratfalls – but no glory either". He found the "engineer's progress and his setbacks are narrated in a patient, tight-lipped present tense, and just as the novel rarely concerns itself with anything that doesn't impinge on the destruction of Les Innocents, so it rarely deviates from its obsessive regime of description and dialogue". He did somewhat temper this, however, stating that "It is one of the historical novel's advantages over the topical or journalistic novel that the benchmark is plausibility rather than verifiable authenticity. Success in this effort requires a capacity for immersion and a degree of imagination, and whatever his shortcomings as a prose writer and a storyteller, Andrew Miller is endowed with both."[21]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The novel was not longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, to the surprise of a number of reviewers.[8][17][22][23] The novel did, however, win the Costa Book Award in 2011 for the "Best Novel" and "Book of the Year".[24][25][26]

Novelist Rose Tremain, writing for The Guardian, identified the novel as one of her two "Books of the year 2011".[27] In 2012, The Observer named it as one of "The 10 best historical novels".[28] It was shortlisted for the 2012 Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction, with judges praising the novel as "a wholly unexpected story, richly imagined and beautifully structured";[29][30] and the South Bank Award in the "Literature" category.[31][32] The novel was also short-listed for the "Independent Booksellers' Week" Book Awards, which are voted for by the public through independent book-shops.[33][34] The marketing campaign for the novel was short-listed in the "Best Overall Package" award by the Book Marketing Society in their Best Marketing Campaign of the Year awards.[35]

Pure was identified as an "Editors' Choice" by The New York Times in June 2012.[36] The novel was also listed on the Belfast Telegraph "Your Top Choice" listing for the best book of the week. Pure has, as of 5 September 2012[update], been listed twelve times; with the first seven being in position 1.[37] NPR listed it as one of their "Critics' Lists" for summer 2012 in the "Rich Reads: Historical Fiction Fit for a Queen" section, nominated by historical fiction author Madeline Miller who stated that "this is historical fiction at its best."[38]

Costa "Book of the Year"

[edit]A structurally and stylistically flawless historical novel, this book is a gripping story, beautifully written and emotionally satisfying. A novel without a weakness from an author who we all feel deserves a wider readership.

Speaking about the novel at the awards ceremony in Piccadilly, London, Miller stated that he "had no special sense of this one being the one" and mentioned that "it's a strange journey, you spend three years in a room on your own and then this: a little unsettling but deeply pleasurable"; "It's a very happy occasion".[40][41] Chair of the judging, editor of the Evening Standard newspaper Geordie Greig, said that the panel were basing their decision partially on the durability and memorability of the work, stating "we were looking for quality".[41]

The judges were undecided over whether the prize should have gone to Matthew Hollis' biography Now All Roads Lead to France instead. The judging panel was locked in a "fierce debate and quite bitter dissent" and eventually used a vote to decide on the winner.[42][43] Geordie Greig said "it was not unpleasant, it was forthright", stating "it's not like comparing apples and oranges – it's like comparing bananas and curry."[42] Chair for the selection in 2010, web editor for Foyles bookshops Jonathan Ruppin, supported the decision, stating "Like Hilary Mantel, who finally became a major name when she won the Man Booker, Miller should now gain the commercial success his stylish and absorbing novels have long deserved." He goes on to say "Pure perfectly captures the mood of a downtrodden and angry nation, on the verge of overthrowing a self-serving and out-of-touch ruling class – it's very much a book for our time."[41]

The 2011 awards were subject to some attention from bookmakers, who offered odds of 2/1 for favourite Matthew Hollis' biography Now All Roads Lead To France and odds of 3/1 for Miller's Pure.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bywater, Michael (26 January 2012). "Pure genius: If you want to understand Davos, start in 1785". The Week. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Clark, Clare (24 June 2011). "Pure by Andrew Miller – review | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "Author Andrew Miller". Foyles.co.uk. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ OReilly, Alison (13 February 2012). "Book Review: Pure by Andrew Miller". Arts and Entertainment North Devon. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Quinn, Thomas (24 February 2012). "Books: Pure by Andrew Miller, Crucible of Secrets by Shona MacLean, Sacrilege by SJ Parris". Big Issue. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Bradbury, Lorna (26 January 2012). "Andrew Miller's novel Pure is a fitting winner of the Costa prize". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "Death, revolution and forgiveness - Features - Books". The Independent. 19 June 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Levasseur, Jennifer (10 September 2011). "Working out where the bodies are buried". The Australian. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Cochrane, Kira (25 January 2012). "Andrew Miller: my morbid obsession | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Das, Antara (19 November 2011). "History vs historical novels". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Kyte, Holly (16 June 2011). "Pure by Andrew Miller: review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Dugdale, John (30 March 2012). "Rise of the copycat book cover | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Pure". Radiolistings.co.uk. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Radio - BBC Radio 4 listings" (PDF). The Irish Times. dublincity.ie. 24 August 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Bath's Bookshop Band has it covered... chapter and verse". Bath Chronicle. HighBeam Research. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Urquhart, James (3 June 2011). "Pure by Andrew Miller – Reviews – Books". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ a b Lynch, Brian (18 June 2011). "Review: Fiction: Pure by Andrew Miller – Books, Entertainment". Irish Independent. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Johnston, Freya (20 June 2011). "Pure by Andrew Miller: review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ a b Feay, Suzi (10 June 2011). "Pure". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Berridge, Vanessa (17 June 2011). "Books :: Book review – Pure by Andrew Miller: Sceptre". Daily Express. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Robson, Leo (17 July 2011). "Pure by Andrew Miller – review | Books". The Observer. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Hephzibah; Pressley, James (22 December 2011). "Miller Wins $47,000 Costa Prize After Judges' 'Fierce' Debate". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (22 January 2012). "Costa prize can deliver a proper verdict | Books". The Observer. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ Battersby, Eileen (4 January 2012). "'Pure' delight for Miller as Costa triumph makes up for Booker disappointment". The Irish Times. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Pressley, James (3 January 2012). "Julian Barnes Loses Whitbread Costa Award to French Graveyard Novel Pure". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "Costa Book Awards 2011 shortlist: Julian Barnes nominated again". The Daily Telegraph. 16 November 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Tremain, Rose (25 November 2011). "Books of the year 2011 | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Skidelsky, William (13 May 2012). "The 10 best historical novels". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ "Walter Scott historical fiction shortlist announced". BBC News. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ "2012 Walter Scott Prize News". Borders Book Festival. 3 April 2012. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Williams, Charlotte (23 April 2012). "Andrew Miller nominated for South Bank award". The Bookseller. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Gallagher, William (2 April 2012). "Sherlock and Twenty Twelve up for South Bank Awards". Radio Times. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Allen, Katie (18 May 2012). "Five Puffin titles on IBW Book Awards shortlists". The Bookseller. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "IBW Book Award Shortlists Announced". Independent Booksellers Week. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "BMS shortlists for Best Marketing Campaign". The Bookseller. 29 May 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ "Editors' Choice". The New York Times. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ "2012 Your Top Choice lists: 28 Jan, 4 Feb, 11 Feb, 18 Feb, 25 Feb, 3 Mar, 10 Mar, 24 Mar, 31 Mar, 7 Apr, 21 Apr, 18 Aug". Belfast Telegraph. HighBeam Research.

{{cite news}}: External link in|title= - ^ Madeline, Miller (23 June 2012). "Rich Reads: Historical Fiction Fit for a Queen". NPR. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Andrew Miller Wins 2011 Costa Book of the Year" (PDF) (Press release). Costa Book Awards. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ "Costa prize: Andrew Miller takes award for novel Pure". BBC News. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Brown, Mark (24 January 2012). "Costa book award: Andrew Miller wins for sixth novel, Pure | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ a b Clark, Nick (25 January 2012). "Literary feud lies behind novel choice for Costa book of the year". The Independent. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ "Andrew Miller wins Costa award for novel 'Pure'". The Irish Times. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Parker, Sam (20 January 2012). "Why Costa Awards Have Bookies in a Flutter: The Rise of Culture Betting". HuffPost. Retrieved 25 January 2012.