Pyramid scheme

A pyramid scheme is a non-sustainable business model that involves the exchange of money primarily for enrolling other people into the scheme, usually without any product or service being delivered. Pyramid schemes have existed for at least a century. Matrix schemes use the same fraudulent non-sustainable system as a pyramid; here, the victims pay to join a waiting list for a desirable product which only a fraction of them can ever receive.

There are other commercial models using cross-selling such as multi-level marketing (MLM) or party planning which are legal and sustainable, although there is a significant grey area in many cases. Most pyramid schemes take advantage of confusion between genuine businesses and complicated but convincing moneymaking scams. The essential idea behind each scam is that the individual makes only one payment, but is promised to somehow receive exponential benefits from other people as a reward. A common example might be an offer that, for a fee, allows the victim to sell the same offer to other people. Each sale includes a fee to the original seller.

Clearly, the fundamental flaw is that there is no end benefit; the money simply travels up the chain, and only the originator (or at best a very few) wins in swindling his followers. Of course, the people in the worst situation are the ones at the bottom of the pyramid: those who subscribed to the plan, but were not able to recruit any followers themselves. To embellish the act, most such scams will have fake referrals, testimonials, and information.

History

Pyramid schemes come in many variations. The earliest schemes involved a chain letter distributed with a list of 5–10 names and addresses on it. The recipient was told to send a specified small sum of money (typically $1 to $5) to the first person of the list. The recipient was then to remove this first person from the list, move all of the remaining names up one place, and to add his own name and maybe more names to the bottom of the list. Then he was to copy the letter with new name list to the individuals listed. It was hoped that this procedure was to be repeated and passed on and then he would be moved to the top of the list and receive money from the others.

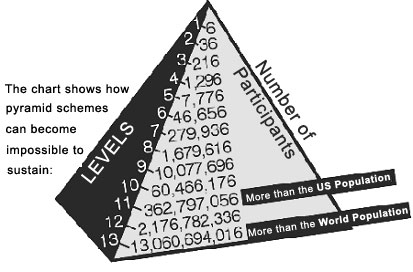

Success in such ventures rested solely on the exponential growth of new members. Hence the name "pyramid", indicating the increasing population at each successive layer. Unfortunately, simple analysis will reveal that within a few iterations the entire global population would need to subscribe in order for pre-existing members to earn any income. This is impossible, and the mathematics of such schemes guarantees that the vast majority of people who participate in these schemes will lose their invested money.

Very large scale pyramid schemes were initiated in post-Soviet states, where people had little familiarity with the stock market and were led to believe that returns in excess of 1000% are feasible. Particularly notorious were the MMM Pyramid schemes in Russia and pyramid schemes in Albania. In the latter case they nearly caused a popular uprising.

Though not a pyramid scheme in the strictest sense, the infamous Ponzi Scheme of Charles Ponzi deserves mention here, due to some similarities.

Identifying features

The distinguishing feature of these schemes is the fact that the product being sold has little to no intrinsic value of its own or is sold at a price out of line with its fair market value. Examples include "products" such as brochures, cassette tapes or systems which merely explain to the purchaser how to enroll new members, or the purchasing of name and address lists of future prospects. The costs for these "products" can range up into the hundreds or thousands of dollars. A common Internet version involves the sale of documents entitled "How to make $1 million on the Internet" and the like. Another example is a product (such as a dial-up modem purportedly using higher speed and/or using Voice over IP) sold at higher than ordinary retail price for the same or similar products elsewhere. The result is that only a person enrolled in the scheme would buy it and the only way to make money is to recruit more and more people below that person also paying more than they should. This extra amount paid for the product is then used to fund the pyramid scheme. In effect, the scheme ends up paying for new recruits through their overpriced purchases rather than an initial "signup" fee.

The key identifiers of a pyramid scheme are:

- A highly excited sales pitch (sometimes including props and/or promos).

- Little to no information offered about the company unless an investor purchases the products and becomes a participant.

- Vaguely phrased promises of limitless income potential.

- No product, or a product being sold at a price ridiculously in excess of its real market value. As with the company, the product is vaguely described.

- An income stream that chiefly depends on the commissions earned by enrolling new members or the purchase by members of products for their own use rather than sales to customers who are not participants in the scheme.

- A tendency for only the early investors/joiners to make any real income.

- Assurances that it is perfectly legal to participate.

The key distinction between these schemes and legitimate MLM businesses is that in the latter cases a meaningful income can be earned solely from the sales of the associated product or service to customers who are not themselves enrolled in the scheme. While some of these MLM businesses also offer commissions from recruiting new members, this is not essential to successful operation of the business by any individual member. Nor does the absence of payment for recruiting mean that an MLM is not a cover for a pyramid scheme. The distinguishing characteristic is whether the money in the scheme comes primarily from the participants themselves (pyramid scheme) or from sales of products or services to customers who aren't participants in the scheme (legitimate MLM).

Market Saturation

The people on the bottom level of the pyramid, no matter how shallow or deep it goes will always lose their money. It is easy to see that the number in the bottom level of the pyramid always exceeds the total of all those in the levels above no matter how many levels there are. If each level must recruit 6 more below them, the ratio of losers to winners is close to 5 to 1 - ~84% of all investors will lose their money. The pyramid in reality would not be perfectly balanced and some members might be able to partially fill their number of recruits, but the same principles apply.

"8-ball" model

Many pyramids are more sophisticated than the simple model. These recognize that recruiting a large number of others into a scheme can be difficult so a seemingly simpler model is used. In this model each person must recruit two others, but the ease of achieving this is offset because the depth required to recoup any money also increases. The scheme requires a person to recruit two others, who must each recruit two others, who must each recruit two others.

Prior instances of this scam have been called the "Plane Game" and the four tiers labeled as "captain", "co-pilot", "crew", and "passenger" to denote a person's level. Another instance was called the "Original Dinner Party" which labeled the tiers as "dessert", "main course", "side salad", and "entree". A person on the "dessert" course is the one at the top of the tree. Another variant "Treasure Traders" variously used gemology terms such as "polishers", "stone cutters" etc. or gems "rubies", "sapphires" etc.

Such schemes may try to downplay their pyramid nature by referring to themselves as "gifting circles" with money being "gifted". Popular scams such as the "Women Empowering Women" do exactly this. Joiners may even be told that "gifting" is a way to skirt around tax laws.

Whichever euphemism is used, there are 15 total people in four tiers (1 + 2 + 4 + 8) in the scheme - the person at the top of this tree is the "captain", the two below are "co-pilots", the four below are "crew" and the bottom eight joiners are the "passengers".

The eight passengers must each pay (or "gift") a sum (e.g. $1000) to join the scheme. This sum (e.g. $8000) goes to the captain who leaves, with everyone remaining moving up one tier. There are now two new captains so the group splits in two with each group requiring eight new passengers. A person who joins the scheme as a passenger will not see a return until they exit the scheme as a captain. This requires that 14 others have been persuaded to join underneath them.

As such, the bottom 3 tiers of the pyramid always lose their money when the scheme finally collapses. Consider a pyramid consisting of tiers with 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 members. The highlighted section corresponds to the previous diagram.

If the scheme collapses at this point, only those in the 1, 2, 4 and 8 got out with a return. The remainder in the 16, 32, and 64 tier lose everything. 112 out of the total 127 members or 88% lost all of their money.

The figures also hide the fact that the confidence trickster would make the lion's share of the money. They would do this by filling the first 3 tiers (with 1, 2, & 4 people) using phony names ensuring they get the first 7 payouts at 8 times the buy-in sum without paying a single penny themselves. So if the buy-in were $1000, they would receive $56,000, paid for by the first 56 investors. They would continue to buy in underneath the real investors, and promote and prolong the scheme for as long as possible to allow them to skim even more from it before the collapse.

In early 2006 Ireland was hit by a wave of schemes with major activity in Cork and Galway. Participants were asked to contribute €20,000 each to a "Liberty" scheme which followed the classic 8-ball model. Payments were made in Munich, Germany to skirt Irish tax laws concerning gifts. Spin-off schemes called "Speedball" and "People in Profit" prompted a number of violent incidents and calls were made by politicans to tighten existing legislation [1]. Ireland has launched a website to better educate consumers to pyramid schemes and other scams [2].

Matrix Schemes

Matrix schemes follow the same laws of geometric progression as pyramids and are subsequently as doomed to collapse as pyramid schemes. Such schemes operate as a queue, where the person at head of the queue receives an item such as a television, games console, digital camcorder etc. when a certain number of new people join the end of the queue. For example ten joiners may be required for the person at the front to receive their item and leave the queue. Each joiner is required to buy an expensive but worthless item such as an e-book for their position in the queue. The scheme organizer profits because the income from joiners far exceeds the cost of sending out the item to the person at the front. Organizers can further profit by starting a scheme with a queue with shill names that must be cleared before genuine people get to the front. The scheme collapses when no more people are willing to join the queue. Schemes may not reveal or may attempt to exaggerate a prospective joiner's queue position which essentially means the scheme is a lottery. Some countries have ruled that matrix schemes are illegal on that basis.

Comparison with Multi-Level Marketing

Examples of successful MLM businesses are Forever Living Products (natural health products from the organically grown aloe vera plant and bee honey), Avon Products, Mannatech, Amway,(sellers of health and beauty products), Quixtar ( e-commerce portal providing hundreds of services and products) ,Tupperware, World Financial Group, ACN Inc., Mary Kay Cosmetics, Nikken and Herbalife (health and wellness products).

These businesses sell sample cases of their products to newly recruited salespersons, and will offer bonuses to members who recruit new salespersons. (These commissions are based on the sale of products, not from an enrollment fee.) These are similarities to pyramid schemes and may lead to the same negative social effects, but these companies consider themselves legal businesses because the recruited staff may receive income solely from the sale of the products of the company, without ever recruiting new salespersons. In reality they are strongly urged to not sell products but to purchase them for self-consumption and to recruit more people to do so, making them functionally equivalent to a pyramid scheme.

See also

- Make money fast

- Large Group Awareness Training (LGAT)

- Ponzi scheme

- Sali Berisha

- Amway

- Autosurfing

- Scam

- Matrix scheme

- MMM (pyramid)

External links

- FTC consumer complaint form

- Article by Financial Crimes Investigator, Bill E. Branscum

- Is Affiliate Marketing just another name for MLM?

- Spoof article

- IMF feature on "The Rise and Fall of Albania's Pyramid Schemes"

- Cockeyed.com presents: Pyramid Schemes - A thorough description of the 8-ball model and matrix schemes which is a close cousin to pyramid schemes.

- National Consumer Agency on Pyramid Schemes - Irish consumer site describes two local pyramid schemes and offers advice to would-be participants.

- Alston Price An example of a typical Pyramid Scheme, located off shore in Belize and operating world wide through the Internet.