Qiu Chuji

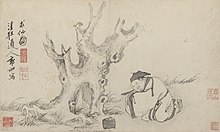

Qiu Chuji (traditional Chinese: 丘處機; simplified Chinese: 丘处机; pinyin: Qiū Chǔjī; 1148 – 23 July 1227), also known by his Taoist name Changchun zi (Chinese: 長春子; pinyin: Chángchūnzi),[1][2] was a Daoist disciple of Wang Chongyang. He was the most famous[3] among the Seven True Daoists of the North.[4] He was the founder of the Dragon Gate sect of Taoism attracting the largest following in the streams of traditions flowing from the sects of the disciples.

History

In 1219 Genghis Khan invited Changchun to visit him[5][6] in a letter dated 15 May 1219 by present reckoning. Changchun left his home in Shandong in February 1220 and journeyed to Beijing. Learning that Genghis had gone West, he spent winter there. In February 1221, Changchun left, traversing eastern Mongolia to the camp of Genghis' youngest brother Otchigin near Lake Buyur in the upper Kerulen - today's Kherlen-Amur basin. From there he traveled southwestward up the Kerulen, crossing the Karakorum region in north-central Mongolia, and arrived at the Altai Mountains, probably passing near the present Uliastai. After traversing the Altai he visited Bishbalig - modern Ürümqi - and moved along the north side of the Tian Shan range to Lake Sutkol, today's Sairam, Almaliq (or Yining City), and the rich valley of the Ili.

From there, Changchun passed to Balasagun and Shu City[disambiguation needed] and across this river to Talas and the Tashkent region, and then over the Syr Darya to Samarkand, where he halted for some months. Finally, through the Iron Gates of Termit, over the Amu Darya, and by way of Balkh and northern Afghanistan, Changchun reached Genghis' camp near the Hindu Kush.

Changchun, had been invited to satisfy the interest of Genghis Khan in "the philosopher's stone" and the secret medicine of immortality. He explained the Taoist philosophy and the many ways to prolong life and was honest in saying there was no secret medicine of immortality.[3] The two had 12 in-depth conversations.[7] Genghis Khan honoured him with the title Spirit Immortal.[4] Genghis also made Changchun in charge of all religious persons in the empire.[8][9][10] Their conversations were recorded in the book Xuan Feng Qing Hui Lu.

The Yenisei area had a community of weavers of Chinese origin and Samarkand and Outer Mongolia both had artisans of Chinese origin seen by Changchun.[11]

Returning home, Changchun largely followed his outward route, with certain deviations, such as a visit to Hohhot. He was back in Beijing by the end of January 1224. From the narrative of his expedition, Travels to the West of Qiu Chang Chun written by his pupil and companion Li Zhichang,[12] we derive some of the most vivid pictures ever drawn of nature and man between the Great Wall of China and Kabul, between the Aral and Yellow Seas.

Of particular interest are the sketches of the Mongols and the people of Samarkand and its vicinity, the account of the land and products of Samarkand in the Ili Valley at or near Almalig-Kulja, and the description of various great mountain ranges, peaks and defiles, such as the Chinese Altay, the Tian Shan, Bogdo Uula, and the Iron Gates of Termit. There is, moreover, a noteworthy reference to a land apparently identical with the uppermost valley of the Yenisei.

After his return, Changchun lived in Beijing until his death on 23 July 1227. By order of Genghis Khan, some of the former imperial garden grounds were given to him for the foundation of a Daoist Monastery of the White Clouds[5] that exists to this day.

Fiction

Qiu Chuji appears as a character in Jin Yong's Legend of the Condor Heroes, Return of the Condor Heroes, and the 2013 film An End to Killing. In Jin Yong's work he is very different from the real persona, described as a 'bullheaded priest' who gets into fights and contests with rivals, very contrary to what his religion preaches. His deeds shape much of the future of the 2 main male characters of the first story.

References

- ^ Li Chih-Ch'ang (16 April 2013). The Travels of an Alchemist - The Journey of the Taoist Ch'ang-Ch'un from China to the Hindukush at the Summons of Chingiz Khan. Read Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-4465-4763-2.

- ^ E. Bretschneider (15 October 2013). Mediaeval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: Fragments Towards the Knowledge of the Geography and History of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th Century:. Routledge. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-1-136-38021-1.

- ^ a b De Hartog, Leo (1989). Genghis Khan - Conqueror of the World. Great Britain, Padstow, Cornwall: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 124–127. ISBN 978-1-86064-972-1. Archived from the original on 2016-10-01.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Quanzhen Tradition". British Taoist Association. Archived from the original on 2009-11-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Li, Chi Ch'ang. "1220 - 1223 : The Travels of Ch'ang Ch'un to the West".

- ^ Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 425–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ^ (Chinese) 胡刃, "成吉思汗与丘处机" 北方新报(呼和浩特) 2014-10-20

- ^ Holmes Welch (1966). Taoism: the parting of the way (revised ed.). Beacon Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-8070-5973-0. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

The Sung was succeeded by the dynasty of the Mongol invaders, or the Yuan. The Yuan saw the zenith of Taoist political fortunes. In 1219 Chingiz Khan, who was at that time in the west, summoned the Taoist monk Ch'ang Ch'un to come and preach to him. Ch'ang Ch'un had succeeded Wang Che as head of the Northern School in 1170; he was now seventy-one years old. Four years later, after a tremendous journey across Central Asia, he reached Imperial headquarters in Afghanistan. When he arrived, he lectured Chingiz on the art of nourishing the vital spirit. "To take medicine for a thousand years," he said, "does less good than to be alone for a single night." Such forthright injunctions to subdue the flesh pleased the great conqueror, who wrote Ch'ang Ch'un after his return to China, asking that he "recite scriptures on my behalf and pray for my longevity." In 1227 Chingiz decreed that all priests and persons of religion in his empire were to be under Ch'ang Chun's control and hat his jurisdiction over the Taoist community was to be absolute. On paper, at least, no Taoist before or since has ever had such power. It did not last long, for both Chingiz and Ch'ang died that same year (1227).

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Daniel P. Reid (1989). The Tao of health, sex, and longevity: a modern practical guide to the ancient way (illustrated ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 46. ISBN 0-671-64811-X. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

Chang Chun: The greatest living adept of Tao when Genghis Khan conquered China; the Great Khan summoned him to his field headquarters in AFghanistan in AD 1219 and was so pleased with his discourse that he appointed him head of all religious life in China.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Joe Hung (June 23, 2008). "Seven 'All True' Greats VII". The China Post. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Jacques Gernet (31 May 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- ^ BUELL, PAUL D. (1979). "SINO-KHITAN ADMINISTRATION IN MONGOL BUKHARA". Journal of Asian History. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 135–8. JSTOR 41930343.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help)

- E. Bretschneider, Mediaeval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources, vol. i. pp. 35–108, where a complete translation of the narrative is given, with a valuable commentary

- C. R. Beazley Dawn of Modern Geography, iii.539.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chang Chun, Kiu". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 840.

External links

- Introduction to Quanzhen Daoism and the Dragon Gate Tradition

- The Travels of Ch'ang Ch'un to the West, 1220-1223, recorded by his disciple Li Chi Ch'ang, translated by E. Bretschneider (includes a translation of Genghis Khan's letter of invitation)

- Qiuchuji's story including timeline and comics - but only the Chinese section works

- The Perfect Man of Eternal Spring Qiu Chuji (In Chinese.)