Ralph Ellison: Difference between revisions

Reverted to revision 477446274 by ClueBot NG: grammar. (TW) |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Writing career== |

==Writing career== |

||

After his third year, Ellison moved to New York City to study the visual arts. He studied sculpture and photography. He made acquaintance with the artist [[Romare Bearden]]. Perhaps Ellison's most important contact would be with the author [[Richard Wright (author)|Richard Wright]], with whom he would have a long and complicated relationship. After Ellison wrote a book review for Wright, Wright encouraged Ellison to pursue a career in writing, specifically fiction. The first published story written by Ellison was a short story entitled "Hymie's Bull," a story inspired by Ellison's hoboing on a train with his uncle to get to Tuskegee. From 1937 to 1944 Ellison had over twenty book reviews as well as short stories and articles published in magazines such as ''New Challenge'' and ''[[New Masses]]''. |

After his third year, Ellison moved to New York City to study the visual arts. He studied sculpture and photography. He made acquaintance with the artist [[Romare Bearden]]. Perhaps Ellison's most important contact would be with the author [[Richard Wright (author)|Richard Wright]], with whom he would have a long and complicated relationship. After Ellison wrote a book review for Wright, Wright encouraged Ellison to pursue a career in writing, specifically fiction. The first published story written by Ellison was a short story entitled "Hymie's Bull," a story inspired by Ellison's hoboing on a train with his uncle to get to Tuskegee. From 1937 to 1944 Ellison had over twenty book reviews as well as short stories and articles published in magazines such as ''New Challenge'' and ''[[New Masses]]''.bitch where my car he said to the ladie |

||

Wright was at that time openly associated with the Communist Party, and Ellison himself was publishing and editing for communist publications although, as historian Carol Polsgrove has written, his "affiliation was quieter." Both Wright and Ellison lost their faith in the Communist Party during [[World War II]] when they felt the party had betrayed African Americans and replaced Marxist class politics for social reformism. In a letter to Wright August 18, 1945, Ellison poured out his anger toward the party leaders. "If they want to play ball with the bourgeoisie they needn't think they can get away with it....Maybe we can't smash the atom, but we can, with a few well chosen, well written words, smash all that crummy filth to hell." In the wake of this disillusion, Ellison began writing ''Invisible Man'', a novel that was, in part, his response to the party's betrayal.<ref>Carol Polsgrove, ''Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement'' (2001), pp. 66-69.</ref> |

Wright was at that time openly associated with the Communist Party, and Ellison himself was publishing and editing for communist publications although, as historian Carol Polsgrove has written, his "affiliation was quieter." Both Wright and Ellison lost their faith in the Communist Party during [[World War II]] when they felt the party had betrayed African Americans and replaced Marxist class politics for social reformism. In a letter to Wright August 18, 1945, Ellison poured out his anger toward the party leaders. "If they want to play ball with the bourgeoisie they needn't think they can get away with it....Maybe we can't smash the atom, but we can, with a few well chosen, well written words, smash all that crummy filth to hell." In the wake of this disillusion, Ellison began writing ''Invisible Man'', a novel that was, in part, his response to the party's betrayal.<ref>Carol Polsgrove, ''Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement'' (2001), pp. 66-69.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:35, 28 February 2012

Ralph Ellison | |

|---|---|

Ralph Ellison | |

| Born | March 1, 1914[1] Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States |

| Died | April 16, 1994 (aged 80) New York, New York, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist, short story writer |

| Genre | Fiction, short stories, criticism |

| Notable works | Invisible Man |

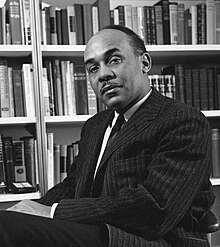

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1914[1] – April 16, 1994) was an American novelist, literary critic, scholar and writer. He was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Ellison is best known for his novel Invisible Man, which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote Shadow and Act (1964), a collection of political, social and critical essays, and Going to the Territory (1986).

Early life

Ralph Ellison, named after Ralph Waldo Emerson,[2] was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, to Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Millsap. Research by Lawrence Jackson, one of Ellison's biographers, has established that he was born a year earlier than had been previously thought. He had one brother named Herbert Millsap Ellison, who was born in 1916. Lewis Alfred Ellison, a small-business owner and a construction foreman, died when Ralph was three years old from stomach ulcers he received from an ice-delivering accident.[2] Many years later, Ellison would find out that his father hoped he would grow up to be a poet.

In 1933, Ellison entered the Tuskegee Institute on a scholarship to study music. Tuskegee's music department was perhaps the most renowned department at the school, headed by the conductor William L. Dawson. Ellison also had the good fortune to come under the close tutelage of the piano instructor Hazel Harrison. While he studied music primarily in his classes, he spent increasing amounts of time in the library, reading up on modernist classics. He specifically cited reading The Waste Land as a major awakening moment for him.

Writing career

After his third year, Ellison moved to New York City to study the visual arts. He studied sculpture and photography. He made acquaintance with the artist Romare Bearden. Perhaps Ellison's most important contact would be with the author Richard Wright, with whom he would have a long and complicated relationship. After Ellison wrote a book review for Wright, Wright encouraged Ellison to pursue a career in writing, specifically fiction. The first published story written by Ellison was a short story entitled "Hymie's Bull," a story inspired by Ellison's hoboing on a train with his uncle to get to Tuskegee. From 1937 to 1944 Ellison had over twenty book reviews as well as short stories and articles published in magazines such as New Challenge and New Masses.bitch where my car he said to the ladie

Wright was at that time openly associated with the Communist Party, and Ellison himself was publishing and editing for communist publications although, as historian Carol Polsgrove has written, his "affiliation was quieter." Both Wright and Ellison lost their faith in the Communist Party during World War II when they felt the party had betrayed African Americans and replaced Marxist class politics for social reformism. In a letter to Wright August 18, 1945, Ellison poured out his anger toward the party leaders. "If they want to play ball with the bourgeoisie they needn't think they can get away with it....Maybe we can't smash the atom, but we can, with a few well chosen, well written words, smash all that crummy filth to hell." In the wake of this disillusion, Ellison began writing Invisible Man, a novel that was, in part, his response to the party's betrayal.[3]

World War II was nearing its end when Ellison, reluctant to serve in the segregated army, chose merchant marine service over the draft. [4] In 1946 he married his second wife, Fanny McConnell. She worked as a photographer to help sustain Ellison. From 1947 to 1951 he earned some money writing book reviews, but spent most of his time working on Invisible Man. Fanny also helped type Ellison's longhand text and assisted her husband in editing the typescript as it progressed.

Published in 1952, Invisible Man explores the theme of man’s search for his identity and place in society, as seen from the perspective of an unnamed black man in the New York City of the 1930s. In contrast to his contemporaries such as Richard Wright and James Baldwin, Ellison created characters that are dispassionate, educated, articulate and self-aware. Through the protagonist, Ellison explores the contrasts between the Northern and Southern varieties of racism and their alienating effect. The narrator is "invisible" in a figurative sense, in that "people refuse to see" him, and also experiences a kind of dissociation. The novel, with its treatment of taboo issues such as incest and the controversial subject of communism, won the National Book Award in 1953.

The award was his ticket into the American literary establishment. Disillusioned by his experience with the Communist Party, he used his new fame to speak out for literature as a moral instrument.[5] In 1955, Ellison went abroad to Europe to travel and lecture before settling for a time in Rome, Italy, where he wrote an essay that appeared in a Bantam anthology called A New Southern Harvest in 1957. Robert Penn Warren was in Rome during the same period and the two writers became close friends.[6] In 1958, Ellison returned to the United States to take a position teaching American and Russian literature at Bard College and to begin a second novel, Juneteenth. During the 1950s he corresponded with his lifelong friend, the writer Albert Murray. In their letters they commented on the development of their careers, the civil rights movement and other common interests including jazz. Much of this material was published in the collection Trading Twelves (2000).

In 1964, Ellison published Shadow and Act, a collection of essays, and began to teach at Rutgers University and Yale University, while continuing to work on his novel. The following year, a survey of 200 prominent literary figures was released that proclaimed Invisible Man the most important novel since World War II.

In 1967, Ellison experienced a major house fire at his home in Plainfield, Massachusetts, in which he claimed more than 300 pages of his second novel manuscript were lost. This assertion is challenged in the 2007 biography of Ellison by Arnold Rampersad. A perfectionist regarding the art of the novel, Ellison had said in accepting his National Book Award for Invisible Man, that he felt he had made "an attempt at a major novel", and despite the award, he was unsatisfied with the book. Ellison ultimately wrote over 2000 pages of this second novel. He never finished it.

Writing essays about both the black experience and his love for jazz music, Ellison continued to receive major awards for his work. In 1969 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom; the following year, he was made a Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by France and became a permanent member of the faculty at New York University as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities, serving from 1970 to 1980.

In 1975, Ellison was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters and his hometown of Oklahoma City honored him with the dedication of the Ralph Waldo Ellison Library. Continuing to teach, Ellison published mostly essays, and in 1984, he received the New York City College's Langston Hughes Medal. In 1985, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts. In 1986, his Going to the Territory was published. This is a collection of seventeen essays that included insight into southern novelist William Faulkner and Ellison's friend Richard Wright, as well as the music of Duke Ellington and the contributions of African Americans to America’s national identity.

Final years

In 1992, Ellison was awarded a special achievement award from the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Ellison was also an accomplished sculptor, musician, photographer and college professor. He taught at Bard College, Rutgers University, the University of Chicago, and New York University. Ellison was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers.

Ralph Ellison died on April 16, 1994, of pancreatic cancer, and was buried at Trinity Church Cemetery[7] in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York City. He was survived by his wife, Fanny Ellison, who died on November 19, 2005.

After his death, more manuscripts were discovered in his home, resulting in the publication of Flying Home and Other Stories in 1996. In 1999, five years after his death, Ellison's second novel, Juneteenth, was published under the editorship of John F. Callahan, a professor at Lewis & Clark College and Ellison's literary executor. It was a 368-page condensation of more than 2000 pages written by Ellison over a period of forty years. All the manuscripts of this incomplete novel were published collectively on January 26, 2010, by Modern Library, under the title Three Days Before the Shooting.[8]

Publications

Fiction

- Invisible Man (Random House, 1952) ISBN 0-679-60139-2

- Flying Home and Other Stories (Random House,at the Square (short story)|A Party Down at the Square]]" (short story) in Gwynn, R. S. (ed). Literature: A Pocket Anthology (4th Edition) (Penguin, 2008) ISBN 0-205-65510-6

- Three Days Before the Shooting (Modern Library, 2010) ISBN 0-375-75953-6

Essays

- Shadow and Act (Random House, 1964) ISBN 0-679-76000-8

- Going to the Territory (Random House, 1986) ISBN 0-394-54050-6

- The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison (Modern Library, 1995) ISBN 0-679-60176-7

- Living with Music: Ralph Ellison's Jazz Writings (Modern Library, 2002) ISBN 0-375-76023-7

Letters

- Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray (Modern Library, 2000) ISBN 0-375-50367-6

Notes

- ^ a b Ellison's birthday has been listed as either 1913 or 1914 by various reputable sources.

- ^ a b Guzzio, Tracie. “Ralph Ellison.” American Writers Retrospective Supplement 2. Ed. Jay Parini. New York. Charles Scribners’s Son’s, 2003. 113-20. Print

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement (2001), pp. 66-69.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, "Divided Minds" (2001), p. 67.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, Divided Minds (2001), pp. 70-72.

- ^ Ealy, Steven D. (2006). "'A Friendship That Has Meant So Much': Robert Penn Warren and Ralph W. Ellison", The South Carolina Review Vol. 38, No. 2: 162-172.

- ^ Find a grave: Ralph Waldo Ellison

- ^ "Three Days Before The Shooting..." Random House. Retrieved Jan. 26, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

Sources

External links

- Template:Worldcat id

- Literary Encyclopedia Biography

- Literary Encyclopedia, Invisible Man

- Ralph Ellison: an American Journey a documentary from California Newsreel

- Soul of a People: Writing America's Story a 90-minute documentary about the WPA Writers' Project

- Biography

- PBS

- Alfred Chester & Vilma Howard (Spring 1955). "Ralph Ellison, The Art of Fiction No. 8". The Paris Review.

- Notes on Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man

- Saul Bellow's 1952 Review of Invisible Man

- Shadowing Ralph Ellison by John Wright

- Photos of the first edition of Invisible Man

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Ellison, Ralph

- Excerpt/on Ralph Ellison, Carol Polsgrove on Writers' Lives, [1]

- 1913 births

- 1994 deaths

- African American essayists

- African American history in Oklahoma

- African American novelists

- African American writers

- American essayists

- American music critics

- American novelists

- Bard College faculty

- Cancer deaths in New York

- Deaths from pancreatic cancer

- Existentialists

- National Book Award winners

- New York University faculty

- People from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Tuskegee University alumni

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- Writers from New York

- Writers from Oklahoma

- Postmodern writers