Erskine Childers (author)

Robert Erskine Childers DSC (25 June, 1870–24 November, 1922) was an author and Irish nationalist who was executed by the authorities of the newly independent Irish Free State during the Irish Civil War. He was the son of British Orientalist scholar Robert Caesar Childers; the cousin of Hugh Childers and Robert Barton; and the father of the fourth President of Ireland, Erskine Hamilton Childers.

Early life

Childers was born in London to a Protestant family originally from Glendalough, Ireland. His father was English and his mother Irish, but he was orphaned as a child and raised by an uncle in County Wicklow.

He was sent to Haileybury College and then studied at Trinity College, Cambridge and after graduation took a job in 1895 as a clerk in the House of Commons. He was an enthusiastic yachtsman, owning several boats during his life and sailing them regularly. At this point in his career he was a supporter of the British Empire.

Marriage

In 1903, Childers visited the United States. There he met and married Mary Alden ("Molly") Osgood, who shared his love of sailing. The two received a small sailing yacht, the Asgard, as a wedding gift.[1]

Military career

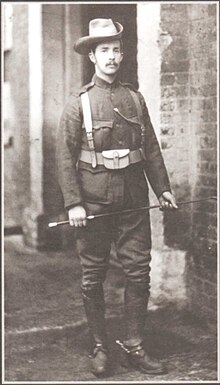

On the outbreak of the Second Boer War in 1899 he volunteered for action, serving as an officer in the City Imperial Volunteers, while he was part of the Honourable Artillery Company in the British Army.

He was wounded in South Africa and invalided back to Britain. . On his return he wrote the novel The Riddle of the Sands, which was published in 1903. Based on his own sailing trips along the German coast, it predicted war with Germany and called for British preparedness. Widely popular, the book has never gone out of print and in 2003, a handful of centenary editions were published. [2]The Observer has listed the book as #37 on its list of "The 100 Greatest Novels of All Time".[3] It has been called the first spy novel[4] (a claim challenged by advocates of Rudyard Kipling's Kim, published two years earlier), and enjoyed immense popularity in the years before World War I. It was an extremely influential book: Winston Churchill later credited[5]( It was also a notable influence on John Buchan)[6] it as a major reason that the Admiralty decided to establish naval bases at Invergordon, Rosyth on the Firth of Forth and Scapa Flow in Orkney. He wrote Volume V of the Times' History of the War in South Africa (1907), which drew attention to British errors in that war and praised the tactics of the Boer guerrillas. He also wrote two books on cavalry warfare based on his experiences, War and the Arme Blanche (1910) and the German Influence on British Cavalry (1911). Both books were strongly critical of the British Army.

Home Rule

Around this time Childers became increasingly attracted to Irish Nationalism and became an advocate of Home Rule. He resigned his post at the House of Commons in 1910 in order to campaign for this cause, writing The Form and Purpose of Home Rule in 1912. In July 1914 he and his wife even smuggled German arms to Howth, County Dublin, in their yacht Asgard, days before the outbreak of World War I. These weapons would later arm the Irish Volunteers during the Easter Rising of 1916. This had been organised in response to the Larne gunrunning of the Ulster Volunteer Force. The remainder of the consignment of guns purchased in Germany for the Irish Volunteers was landed a week later at Kilcoole, county Wicklow by Sir Thomas Myles from his own yacht, the Chotah.

With the start of war, Childers joined the Royal Navy as an Intelligence Officer and was active in the North Sea and the Dardanelles. He was awarded the DSC for bravery and was promoted to Lieutenant Commander in the RNVR in 1916. He was also made [7]Honorary Secretary of the Maritime branch of the Legion of Frontiersmen in London.

However the violent suppression of the Easter Rising had angered Childers, and after the war he moved to Dublin to become fully involved in the struggle against British rule. He joined Sinn Féin, forming a close association with Éamon de Valera and Michael Collins.

In 1919 he was made Director of Publicity for the First Irish Parliament and attempted to represent the Irish Republic at the Versailles conference in Paris. In 1920 Childers published Military Rule in Ireland, a strong attack on British policy. In 1921 he was elected (unopposed) to the Dáil as member for Wicklow and published the pamphlet Is Ireland a Danger to England?, which attacked the British prime minister, David Lloyd George. He became editor of the Irish Bulletin after the arrest of Desmond FitzGerald.

Civil War and death

Childers was secretary-general of the Irish delegation that negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty with the British government. He stayed at the delegation headquarters in Hans Place throughout the period of the negotiations, 11 October–6 December 1921. Childers became vehemently opposed to the final draft of the agreement, particularly the clauses that required Irish leaders to take an Oath of Allegiance to the British king. The Treaty bitterly divided Sinn Féin and the IRA, and Ireland descended into civil war in June 1922.

Said to be the inspiration behind the irregulars' propaganda, Childers was hunted by National Army soldiers and had to travel secretly. The ambush death of Michael Collins intensified the desire of Free State authorities to exact retribution, and in September 1922 the Irish Dáil introduced the Emergency Powers legislation, establishing martial law powers and new capital offences for the carrying of firearms without licence.[8] In November of the same year, Childers was arrested by Free State forces at his home, Glendalough, in County Wicklow, while travelling to meet De Valera. He was tried by a military court on the pretext of possessing a small-calibre automatic pistol on his person in violation of the Emergency Powers Resolution.[9] Ironically, the pistol was alleged to be a gift from Michael Collins before the latter swore allegiance to the Free State.[10] Childers was convicted by the military court and sentenced to death. While his appeal of the sentence was still pending, Childers was executed by firing squad at the Beggar's Bush Barracks in Dublin. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

Before his execution, in a spirit of reconciliation, Childers obtained a promise from his then 16-year-old son, the future President Erskine Hamilton Childers, to seek out and shake the hand of every man who had signed his father's death warrant. [11] Childers himself shook hands with each member of the firing squad that was about to execute him. His last words, spoken to them, were (characteristically) in the nature of a joke: [12] "Take a step or two forward, lads. It will be easier that way."

Winston Churchill, who had actively pressured Michael Collins and the Free State government to crush the rebellion by armed force, expressed the British view of Childers at the time: "No man has done more harm or done more genuine malice or endeavoured to bring a greater curse upon the common people of Ireland than this strange being, actuated by a deadly and malignant hatred for the land of his birth."[13] In Ireland, however, many saw Childers's execution as politically-motivated revenge, an expedient method of halting the continuing flow of anti-British political texts for which Childers was widely credited.

It was the express wish of Mary Childers, upon her death in 1964, that any writings based upon the extensive and meticulous collection of papers and documents from her husband's in depth involvement with the Irish struggles of the 1920's, be locked away from anyone eyes until 50 years after his death [14]. Thusly, in 1972 , Erskine Hamilton Childers started the process of finding an official Biographer [15]. In 1974, Andrew Boyle (previous biographer of Brendan Bracken, Lord Reith amongst others) was given the task of exploring the vast Childers archive, and his "official" biography of Robert Erskine Childers was finally published in 1977 [16] , [17].

References

- Childers, Erskine. In the Ranks of the C.I.V., London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1901.

- Coogan, Tim Pat. The IRA: A History, Niwot, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1993.

- Costello, Peter, The Heart Grown Brutal: The Irish Revolution in Literature from Parnell to the Death of Yeats, 1891-1939, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1977.

- Wilkinson, Burke, The Zeal of the Convert: The Life of Erskine Childers, Sag Harbor, New York: Second Chance Press, 1985

Notes

- ^ The Asgard

- ^ http://books.guardian.co.uk/news/articles/0,6109,1061083,00.html

- ^ Drummond, Maldwin, Introduction, The Riddle of the Sands by Childers, Erskine (Author), London: The Folio Society; 1st edition (1992)

- ^ http://www.randomhouse.com/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780375720253

- ^ Knightley, Phillip. The Second Oldest Profession: Spies and Spying in the Twentieth Century. London: Pimlico. pp. p17. ISBN 1844130916.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Clark, Ignatius (1992). Voices prophesying war, 1763-1984. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. pp142-3. ISBN 0192123025.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:FrontiersmenRecruitingPoster.jpg

- ^ Cumann na nGaedhael

- ^ Coogan, Tim Pat, The IRA: A History, Niwot, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1993; Wilkinson, Burke, The Zeal of the Convert: The Life of Erskine Childers, Sag Harbor, New York: Second Chance Press, 1985

- ^ Wilkinson, Burke, The Zeal of the Convert: The Life of Erskine Childers, Sag Harbor, New York: Second Chance Press, 1985

- ^ On Soundings - TIME

- ^ Boyle, Andrew. The Riddle of Erskine Childers. London, Hutchinson, 1977, P. 25

- ^ Boyle, Andrew. The Riddle of Erskine Childers. London, Hutchinson, 1977, P. 22. From a speech given by Winston Churchill, 11 November 1922 (Dundee)

- ^ Boyle, Andrew. The Riddle of Erskine Childers. London, Hutchinson, 1977, pp. 8-10

- ^ Boyle, Andrew. The Riddle of Erskine Childers. London, Hutchinson, 1977, pp. 8-10

- ^ Boyle, Andrew. The Riddle of Erskine Childers. London, Hutchinson, 1977

- ^ http://janus.lib.cam.ac.uk/db/node.xsp?id=EAD%2FGBR%2F0016%2FCHILDERS

External links

- Piper, Leonard. Dangerous Waters: The Life and Death of Erskine Childers (aka The Tragedy of Erskine Childers (Hambledon) (2003). ISBN 1852853921.

- Ring, Jim Erskine Childers: A Biography (John Murray).

- Boyle, Andrew. "The Riddle Of Erskine Childers" (Hutchinson) (1977) ISBN 0091284902.

- McInerney, Michael "The Riddle Of Erskine Childers : Unionist & Republican" (E & T O'Brien) (1971) ISBN 0950204609

- Works by Erskine Childers at Project Gutenberg

- Free ebooks of "Riddle of the Sands" and "In the Ranks of the CIV", optimized for printing, plus selected Childers bibliography

- Childer's rebuttal to the Dail in 1922 that he had served in the British Secret Service.

- Newsreel Movie Footage of Robert Erskine Childers in London, circa 1921 , Courtesy of British Pathe. [1]

- 1870 births

- 1922 deaths

- British non-fiction writers

- British novelists

- Irish politicians

- People from London

- Old Haileyburians

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Honourable Artillery Company

- British military personnel of the Boer War

- Royal Navy personnel of World War I

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross

- People of the Irish Civil War

- Members of the 2nd Dáil

- Teachtaí Dála

- Burials at Glasnevin Cemetery

- Irish Republican Army members 1917-1922

- Irish Republican Army members 1922-1969

- People executed by firing squad

- Legion of Frontiersmen members

- Irish executions

- Royal Navy officers