Hippocamp (moon)

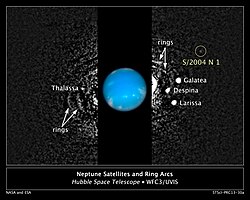

Composite of Hubble Space Telescope images from 2009 showing Neptune, S/2004 N 1, and some of Neptune's rings and other inner moons. The brightness of the moons relative to Neptune is greatly enhanced. | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | M. R. Showalter, I. de Pater, J. J. Lissauer, R. S. French[1] |

| Discovery date | July 1, 2013 |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| ~ 105,283 km | |

| Eccentricity | ~ 0.000[3] |

| 0.9362 d[2] | |

| Inclination |

|

| Satellite of | Neptune |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 8-10 km[2] | |

| Albedo | assumed low |

| 26.5[2] | |

S/2004 N 1[Note 1] is a small moon of Neptune, about 18 km in diameter, that was discovered in 2013, bringing Neptune's retinue of known moons to fourteen.[4] The moon is so dim that it was not observed by the Voyager 2 spacecraft that flew by in 1989. Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute found it in July 2013 by analyzing archived photographs of Neptune taken by the Hubble Space Telescope from 2004 to 2009.[5] S/2004 N 1 completes one revolution around Neptune in just under one Earth day.

Discovery

Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute discovered S/2004 N 1 in July 2013 when examining Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images of Neptune's ring arcs from 2009 using a technique similar to panning to compensate for orbital motion.[4][6] On 1 July 2013, after deciding "on a whim" to expand the search area to radii well beyond the rings,[7] he found the "fairly obvious dot" that represented the new moon.[2] He then found the satellite in other archival HST images going back to 2004. Voyager 2, which had observed all of Neptune's other inner satellites, did not detect the moon during its 1989 flyby, due to its dimness.[4] Given that the discovery images have long been available to the public, the moon could have been found by anyone.[2]

S/2004 N 1 is the fourteenth known moon of Neptune, and the first Neptunian moon discovery to be announced since September 2003.

Origin

Neptune's largest moon, Triton, which has a retrograde and inclined orbit, is thought to have been captured from the Kuiper belt well after the formation of Neptune's original satellite system. The pre-existing moons would have had their orbits shifted by the capture process, which would have ejected some and caused collisions that must have destroyed others.[8][9] Neptune's present inner satellites are thought to have then accreted from the resulting rubble after Triton's orbit was circularized by tidal deceleration.[10]

Physical properties

It is assumed that S/2004 N 1 has a surface as dark as "dirty asphalt"[6] comparable with those of Neptune's other inner satellites, whose geometrical albedos (reflectivities) range from 0.07 to 0.10.[11] S/2004 N 1's apparent magnitude of 26.5 would then give it a diameter of 16 to 20 kilometres, making it the smallest of Neptune's known moons.

The near-infrared spectra of Neptune's rings and inner moons have been examined with the HST NICMOS instrument.[12][13] The data obtainable is consistent with similar dark, reddish material being present on all their surfaces, and suggests organic material containing CH and/or -CN bonds.[13] The spectral resolution did not allow the molecular constituents of the surfaces to be identified, however. Water ice is also thought to be present, but unlike the case of small Uranian moons, its spectral signature could not be observed.[13]

Orbital properties

S/2004 N 1 completes one revolution around Neptune every 22 hours and 28.1 minutes (0.9362 days),[2] implying a semi-major axis of 105,283 km, just over a quarter that of Earth's moon, and roughly twice the average radius of Neptune's rings. Both its inclination and eccentricity are close to zero.[2] It orbits between Larissa and Proteus, making it the second outermost of Neptune's regular satellites. Its small size at this location runs counter to a trend among the other regular Neptunian satellites of increasing diameter with increasing distance from the primary. Given Neptune's rotational period of 0.6713 day,[14] S/2004 N 1 is the innermost known moon of the system to be outside a synchronous orbit and thus not to be undergoing tidal deceleration.

The periods of Larissa, S/2004 N 1, and Proteus are within about one percent of a 3:5:6 orbital resonance.[Note 2] Larissa and Proteus are thought to have passed through a 1:2 mean-motion resonance a few hundred million years ago;[15][16] Proteus and S/2004 N 1 have drifted away from Larissa since then because the former two are outside a synchronous orbit (and are being tidally accelerated) while Larissa is within one.

Naming

The discovery team plans to submit a name proposal to the IAU based on a figure from Greco-Roman mythology with a relationship to Poseidon/Neptune, the god of the sea,[7] consistent with the naming of other moons of Neptune.

Notes

- ^ Moons are given provisional designations when they are first discovered. The year refers to when the data was acquired, not to when the moon was discovered.

- ^ Given the moons' respective periods of 0.55465, 0.93618 and 1.12231 days, the actual period ratio is 3.000:5.064:6.070.

References

- ^ Yeomans, D. K. (2013-07-15). "Planetary Satellite Discovery Circumstances". JPL Solar System Dynamics web site. Jet Propulsion Lab. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Kelly Beatty (15 July 2013). "Neptune's Newest Moon". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ a b Editors of Sky & Telescope. "A Guide to Planetary Satellites". Sky & Telescope web site. Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ a b c "Hubble Finds New Neptune Moon". Space Telescope Science Institute. 2013-07-15. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- ^ "Nasa's Hubble telescope discovers new Neptune moon". BBC News. 2013-07-15. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- ^ a b Showalter, M. R. (2013-07-15). "How to Photograph a Racehorse ...and how this relates to a tiny moon of Neptune". Mark Showalter's blog. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b Klotz, I. (2013-07-15). "Astronomer finds new moon orbiting Neptune". Reuters. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- ^ Goldreich, P. (1989). "Neptune's story". Science. 245 (4917): 500–504. Bibcode:1989Sci...245..500G. doi:10.1126/science.245.4917.500. PMID 17750259.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Agnor, C. B.; Hamilton, D. P. (2006-05-11). "Neptune's capture of its moon Triton in a binary–planet gravitational encounter". Nature. 441 (7090): 192–194. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..192A. doi:10.1038/nature04792. PMID 16688170.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1016/0019-1035(92)90155-Z , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1016/0019-1035(92)90155-Zinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00002-2 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00002-2instead. - ^ Dumas, C.; Terrile, R. J.; Smith, B. A.; Schneider, G. (2002-03). "Astrometry and Near-Infrared Photometry of Neptune's Inner Satellites and Ring Arcs". The Astronomical Journal. 123 (3): 1776–1783. doi:10.1086/339022. ISSN 0004-6256.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Dumas, C.; Smith, B. A.; Terrile, R. J. (2003-08). "Hubble Space TelescopeNICMOS Multiband Photometry of Proteus and Puck". The Astronomical Journal. 126 (2): 1080–1085. doi:10.1086/375909. ISSN 0004-6256.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Williams, David R. (1 September 2004). "Neptune Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Zhang, K.; Hamilton, D. P. (2007-06). "Orbital resonances in the inner neptunian system: I. The 2:1 Proteus–Larissa mean-motion resonance". Icarus. 188 (2): 386–399. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.12.002. ISSN 0019-1035.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Zhang, K.; Hamilton, D. P. (2008-01). "Orbital resonances in the inner neptunian system: II. Resonant history of Proteus, Larissa, Galatea, and Despina". Icarus. 193 (1): 267–282. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.08.024. ISSN 0019-1035.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)